Fot the third consecutive year, DMovies attended what has quickly become a meeting point for filmmakers, industry pundits and movie enthusiasts from every corner of the planet. The Festival took place during 10 days, between November 30th and December 9th at the heart of the coastal city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. In total, it screened 126 films from 77 countries, and in 47 languages. The extravagant red carpet ceremonies attracted Arab and international stars alike, including Sharon Stone, Catherine Deneuve, Amina Khalil, Diane Kruger, Ranveer Singh, Paz Vega, Johnny Depp, Will Smith, Burak Özçivit, and many others.

…

.

Programming secrets

I asked the Director of International Programming Kaleem Aftab about their programming secrets: “We divide programming into two departments, the Arab programming department and the international one. We talk to each other all the time, and only at the highest level between myself and Antoine Khalife, who’s the director of our Arab programme. Each one of us has their own team. On my team, I have six full-time programmers. Plus, there are the film liaisons we work with who occasionally help because this year we got so many more submissions than previous years. Only African, Arab and Asian films can submit through the online system. Last year through that method we had 400 films coming. And this year we had over 1400! So the number of hours we had with the size of team was probably not enough. So it was good to have a larger support mechanism because it’s very tricky to go through so many films. Plus, we have all of the films playing the film festivals and the films that sales agents send us directly. By the start of September, we have seen everything”.

He goes on to explain how his peer works: “Antoine has a team of four people. They look at the Arab films throughout the year. The Red Sea Fund and the Red Sea Lodge do so much work with either developing Arab film or financing Arab films. We’ve been watching the Arab films cut by cut over the years, so we have a much better footing of what it is. In the field of Arab and Saudi films, there are probably around 1,200 to 1,500 movies made, including shorts”.

I also asked Kaleem what makes an Arab film, and whether a British movie could ever qualify as “Arab”. He responded: “We have 22 Arab countries. It’s on the website which we consider Arab because there’s a lot of there are some vagaries. And then we also consider anyone who has an Arab, African or Asian passport who lives in another country. But the director has to have the passport and the film has to be about the Arab and Asian world.

.

Challenging orthodoxies

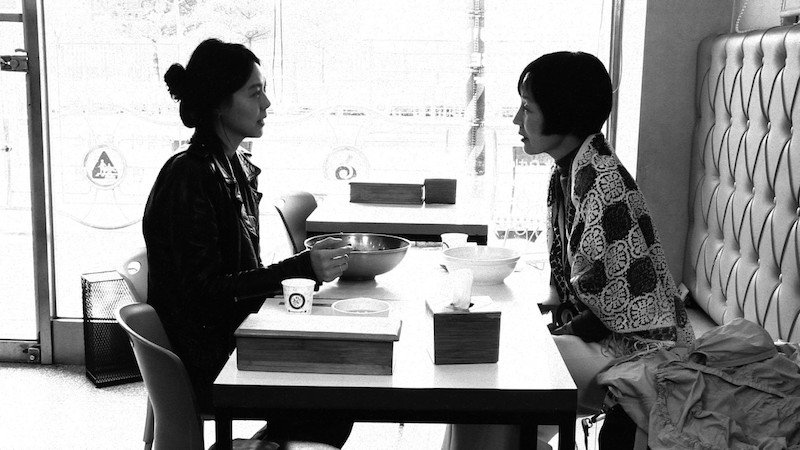

The programme of the Red Sea International Film Festival is surprisingly audacious and diverse. The most recurring topic is female oppression and empowerment (Amjad Al Rasheed’s Inshallah A Boy, Humaid Alsuwaidi’s Dalma, In Flames, (Zarrar Kahn), and many others). Certain films question the mechanisms of religious oppression, while others even shed a positive light portrayal of LGBT+ characters.

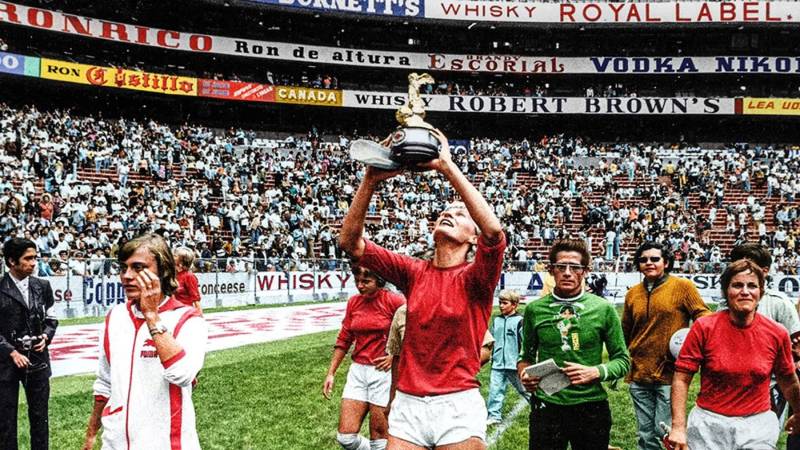

Kaleem and his team picked a very special British film for this year’s edition of the Red Sea. “We’re showing Copa 71 (Rachael Ramsay and James Erskine), which was the first attempt to put on a women’s football tournament. This is the story of women who are saying no to the old powers. It goes into the history of women’s football, when it was banned, and how it was extremely popular in the early 20th century. So I felt that in a country such as Saudi Arabia, a place where women’s rights and gender rights are changing a lot, it would be great not only to bring Copa 71, but also to make it a gala”. A little masterpiece indeed, and an eye-opening movie that needs to be seen in Britain and the Arab world alike.

And Copa 71 isn’t the exception. There is not shortage of female directors at the Red Sea. “This year we have 31 female-led movies”, Kaleem notes.

.

Different sensibilities

The Festival boasts a large number of strong Iranian movies, such as The Last Snow (Amirhossein Asgari) and Roxana (Parviz Shahbazi). Iranian cinema has always fascinated me. And it’;s remarkably different from Saudi cinema. Iranian cinema is contemplative and reflexive, while Saudi cinema drinks from the same water as Hollywood, I opined. Kaleem disagrees: “I don’t believe that Saudi cinema drinks from the same water as Hollywood. I think it’s too early to say that. The Red Sea Film Festival has only been going for three years. This is the first time in four decades we’ve been trying to develop a Saudi film culture. Maybe in four or five years we’ll actually see the sensibility of Saudi films“.

He shares my passion for Persian movies: “We all know the values and merits of Iranian cinema, the poetic way that they deal with tricky subjects. Iranian cinema is wonderful, as everybody in the world knows. We were joking as we were watching the films that this could just have an Iranian film festival because there was so many good films submitted. We had to reject so many good films that we loved just because of the sheer weight and volume”.

.

The winners and the dirty gems

The big winners were as follows:

- Golden Yusr for Best Feature Film: In Flames, (Zarrar Kahn);

- Silver Yusr for Best Feature Film: Dear Jassi (Tarsem Singh);

- Jury Prize: The Teacher (Farah Nabulsi);

- Best Director: Sunday (Shokir Kholikov);

- Best Actor: Saleh Bakri, in The Teacher;

- Best Actress: Mouna Hawa in Inshallah A Boy;

- Best Screenplay: Karim Bensalah and Jamal Belmahi of Six Feet Over (Bensalah);

- Asharq Documentary (Best Documentary In Competition): Four Daughters (Kaouther Ben Hania);

- Film AlUla Audience Award: Saudi Film: Norah (Tawfik Alzaidi);

- Film AlUla Audience Award: Non-Saudi Film: Hopeless (Kim Chang0-hoon); and

- Best Cinematic Contribution: Omen (Baloji).

Prizes were given a jury presided by Australian filmmaker Baz Lurhmann. He was joined by jury members Joel Kinnaman, Freida Pinto, Amina Khalil, Paz Vega, Hana Alomair and Fatih Akin.

My dirty favourites were the following four films, all awarded our five splats (a filthy genius rating):

- The heart-ripping Jordanian social-realist drama about faking a pregnancy Inshallah a Boy;

- The luminescent Iranian rural drama The Last Snow;

- The sobering British documentary about erasing women’s football from history Copa 71; and

- The equally elegant and terrifying Emirati exorcism horror Three (Nayla Al Khaja).

.

Our coverage

With a little helping hand from American journalist Joshua Bogatin and Brazilian writer Duda Leite, we published a total of 38 pieces this year. This includes five interviews (with Baloji, Rachel Ramsay, Kaouther Ben Hania, Tamer Ruggli, and the Malaysian tigress Amanda Nell Eu), as well as nine republished reviews of films that we watched earlier this year in other festivals. You can read them all by clicking here.

Picture at the top by Victor Fraga. Middle picture is a still from ‘Inshalah a Boy’. The last image is a still from ‘Copa 71’.