We first meet the hero of Askar Uzabayev’s latest film, Happiness, standing in front of the mirror. Pulling down her bathrobe to reveal her naked chest and shoulders, illuminated only by candlelight due to regular power outages, she inspects her many bruises. Played by actress Laura Myrzakhmetova, but named archetypically as just “Wife”, she is one of millions of women across Kazakhstan living under the brutal spectre of domestic violence.

This issue is of epidemic proportions. As producer Bayan Maxatkyzy tells me, “Every year, about 400 women die from domestic violence. Only seven per cent of victims report domestic violence, despite nearly one in two women in the country suffering some sort of abuse. And this is just the official data. There could be more.” And with no official law for the protection of victims, “thousands of abusers get away with this crime on a daily basis.”

Maxatkyzy suffered intense domestic abuse herself, but counts herself as one of the lucky ones. She’s a genuine movie star in Kazakhstan, talking to me across Zoom while wearing large sunglasses and sitting on an opulent couch with an expensive-looking handbag in full-view. Rising to fame for her role in the popular 1993 Kazakh melodrama Love Station followed by a successful journalism and acting career, she has four million Instagram followers, more than any other celebrity in the country. So, when her first husband, Bakhytbek Yesentayev, beat and stabbed her four times in 2016, the story became national news, eventually leading to his 9-year imprisonment.

Maxatkyzy’s fame give her case widespread attention, but the woman at the heart of Happiness, which recently won the Panorama Audience Award at the Berlin Film Festival, has no such protection. The first half is utterly drenched in sadness and desperation, a culture of misogyny permeating almost every scene. Her daughter (Almagul Sagyndyk) is getting married, yet nobody seems to be celebrating. The perennially drunk Husband (Yerbolat Alkozha) tells the bride-to-be in an embarrassing liquor-sodden speech to “never raise your voice” if she is to be a good wife, displaying a cycle of submissiveness and shame handed down from generation to generation.

When he later rapes his own wife on his daughter’s wedding night, a cardboard cut-out of a beautiful woman wrapped in clingfilm lingers in the background; an ironic contrast of feminine perfection that perhaps represents the ideal, voiceless woman. Despite her tragic home life, the Wife works as an influencer, selling perfume that she promises will give other women happiness.

In her posts, the Wife lays out a rehearsed theory, underscored by Antonio Vivaldi’s “Winter”. She says that happiness is 50 per cent nature, 10 per cent living conditions, and 40 per cent a result of free will. But the reality of the film, imbued with endless beatings, police corruption and sexual menace, lives within that middle 10 per cent, resulting in a horrifying, hard-to-look-away portrayal of living under the fear of death with little chance of state protection.

Both Maxatkyzy and director Askar Uzabayev, who adapted a script co-written with journalist Assem Zhapisheva, avoided state financing models when finding funding for the film. Maxatkyzy crowdfunded $20,000, with many women “sending one, two dollars” to the cause. “As many rich producers are men, and this was [Kazakhstan’s] first movie about domestic violence, they didn’t want to take part. Because they are men,” Maxatkyzy says. “Maybe they just didn’t believe in this project.” Uzabayev also believes the crowdfunding was the right choice. “When the government pay, they tell us what to do, like not showing police corruption,” he says.

The film takes a freewheeling turn by the end, anchored by Myrzakhmetova’s performance. The actress both empowers and teases out the nuances of her unnamed hero, who is neither victim nor a stereotypical “strong woman”. But Myrzakhmetova was not the first choice for the role. In fact, according to Uzabayev, “six candidates before Laura rejected the role. Our last candidate refused to take it two days before we planned to start shooting. In the beginning [the actresses] were inspired, but after discussions with their husbands, they were prohibited from taking this role.”

The film’s overwhelming atmosphere of shame and fear, coupled with the wider, grim context, is a far-cry from stereotypical Hollywood portrayals like The Invisible Man or Promising Young Woman, which can lean more poppy, revenge-laden and digestible. Happiness is so powerful because it doesn’t borrow inspiration from genre cues, such as the meticulously-planned revenge or a final belief in the police to fix the problem, and pursues its own uncompromising, highly distressing path. As Maxatkyzy says, “We didn’t take ideas from American or European movies because our mentality is completely different. Our society is totally patriarchal.” Her hope is that the movie will be widely-seen in order to start a conversation, both in Kazakhstan and further afield: “My intention is that people will remember situations that happened among their own families. I hope the inconvenience that they feel will lead to the realisation that they could take action to change the situation.”

Happiness premiered at the Berlinale. Stay tuned for a wider release.

…

.

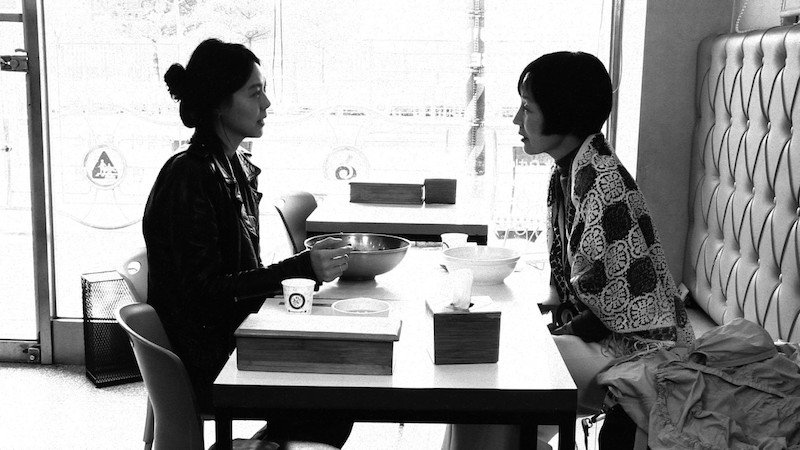

All images in this article are stills from ‘Happiness’.