Trust my luck: despite having seen 15 of the 18 entries in the Berlin Film Festival competition, I missed Alcarràs, Carla Simón’s second feature and the Golden Bear winner. Congratulations to her, although I cannot possibly pass judgement on the victory considering I have not seen the film. Having also missed Synonyms (Nadav Lapiud) in 2019, Touch me Not (Adina Pintilie) in 2018, Body or Soul (Ildiko Enyedi) in 2017 and Fire at Sea (Gianfranco Rosi) in 2016, I am obviously cursed.

Perhaps Alcarràs is a masterpiece, but the buzz around it didn’t suggest an unequivocal five-star film. In fact, throughout my entire foray through the Competition, there was only one film that will stay with me forever: Ulrich Seidl’s Rimini, a fantastic, multifaceted, debate-provoking work that naturally went home without a single award. I thought it might at least win best performance for Michael Thomas, who remains constantly compelling and larger-than-life throughout. But he lost to a worthy winner, the fantastic Meltem Kaptan, who simply transforms Andreas Dresen’s Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush (pictured below) through sheer force of personality alone.

It’s a strange year when, despite severe dialect differences between North Tyrol and Bremen, the two best competition entries are in the German language. Carlo Chatrian, in his third year as the artistic director, and generally doing a good job shaking the Festival up while sticking to its experimental roots, promised less politics and more love stories this year.

Despite this, the politically-minded tales were invariably more interesting than the preponderance of middling to bad French and Franco-German romances — films like Claire Denis’ Both Sides of the Blade, Nicolette Krebitz’s A E I O U – A Quick Alphabet of Love and François Ozon’s Peter Von Kant (pictured at the top of this article) -that dominated the competition this year. Occasionally, these safe middle-European choices resulted in Mikhaël Hers’s lovely Passengers of the Night (no awards, pictured below), but most of these picks would have felt more comfortable for the less provocative Special Gala section.

Further afield, francophiles worldwide have had a field day, considering that Rithy Panh’s Everything Will Be Ok (the rare entirely political film that fell apart in its ponderous narration), Ursula Meier’s The Line (feature image) and Denis Côté’s That Kind of Summer were also in French while being from Cambodia, Switzerland and Quebec respectively. Honestly, what’s left for Cannes?

Along with an overall ARTE-sanctioned, EU-friendly aesthetic, whiteness, middle-age and heterosexuality was the name of the game: over and over again. I’m not usually the one to care too much about film festivals being diverse just for the sake of it, but I felt the lack of worldwide perspectives here in favour of a particularly played-out white, straight sexuality. Films that tried to do something a bit different like Isaki Lacuesta’s One Year, One Night, looking at the after-effects of the Bataclan attacks, barely interrogated the current political situation in Europe, aiming instead at pop-psychology and banal romantic drama.

In this respect, Rimini, which actively confronted the ugliness at the heart of the continent, or Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush, which forthrightly criticised the issues of American imperialism across the world and how that can even be felt in Europe, felt far more honest, and heartfelt.

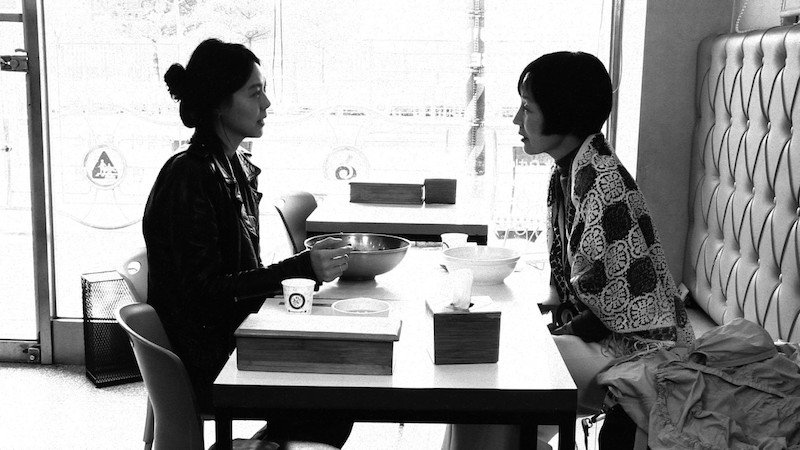

The few Asian exceptions, like Indonesia’s Before, Now & Then (Kamila Andini), China’s Return to Dust (Li Ruijun) and Korea’s The Novelist’s Film (Hong Sangsoo, pictured below) were often more psychologically fascinating and aesthetically innovative than their European counterparts, but I can’t claim to even truly love those films either. Then from North and Central America was Natalia López Gallard’s indecipherable Robe of Gems and Phyllis Nagy’s Call Jane (which I missed), neither of which dominated critical conversation at the festival. Eastern Europe, Central Asia, South America, Africa and Australasia were completely absent.

It’s sad to say, considering how much I love the Berlinale, and how I actually consider myself to be rather generous, but this year was probably the worst I’ve attended. Perhaps the pandemic has made it difficult, perhaps the Franco-German alliance is a little too strong, perhaps I am particularly cynical this time round, but the festival might do well to ditch the love stories next year. Failing that, maybe they can just find better ones instead.

Full List of Awards:

Golden Bear

Alcarràs (Carla Simón)

Silver Bear: Grand Jury Prize

The Novelist’s Film (Hong Sang-soo)

Silver Bear: Jury Prize

Robe of Gems (Natalia Lopez Gallardo)

Silver Bear for Best Director

Claire Denis (Both Sides of the Blade)

Silver Bear for Best Leading Performance

Meltem Kaptan (Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush)

Silver Bear for Best Supporting Performance

Laura Basuki (Before, Now & Then)

Silver Bear for Best Screenplay

Laila Stieler (Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush)

Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution

Rithy Panh (Everything Will Be Ok)

Silver Bear: Special Mention

A Piece of Sky (Michael Koch)