This year’s Transylvania Film Festival, the biggest film festival in Romania, comes with a challenge: “make films, not war.” Representing a country that borders both war-torn Ukraine and close-friends Moldova — also under threat from Russian aggression — TIFF is deeply committed to showing off the best of cinema in extremely troubled times.

While cinema itself cannot offer the vaccine, it might be able to offer a balm; as shown by their prior success in putting on in-person events in 2020 and 2021 while other summer festivals switched to digital-only editions. Set in Cluj-Napoca — known as Romania’s second city after Bucharest, and often touted as its creative centre and an LGBT hub — the 21st edition of the festival switches its attention to the war in Ukraine, not through furthering division but by allowing the power of cinema to show off our common humanity.

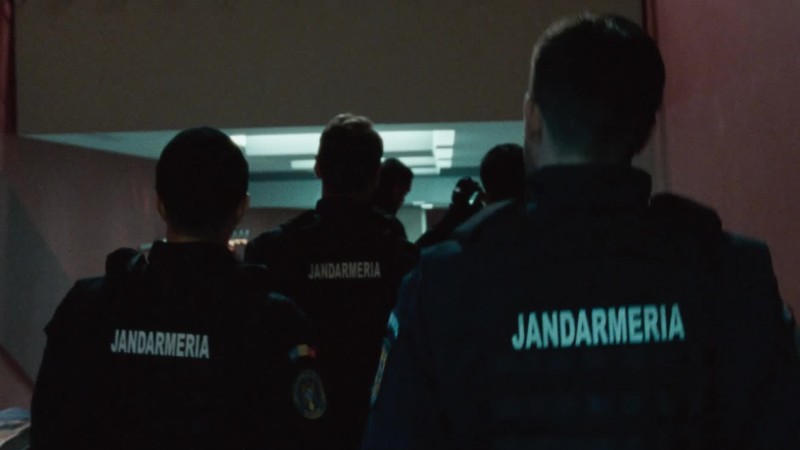

Therefore, while Ukrainian refugees and citizens are given free access to films at the festival, and Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk’s Ukrainian Pamfir (pictured above) is a hotly anticipated title, Russian films aren’t completely cut off either. Kirill Serebrennikov’s 2021 Cannes film Petrov’s Flu plays, as well as Lado Kvataniya’s serial killer drama The Execution. The latter plays as part of the competition series, which focuses on first and second features, and has counted films such as Babyteeth (Shannon Murphy, 2020), Oslo 31st August (Joachim Trier, 2012) and Cristian Mungiu’s debut Occident (2002) among its previous winners.

In fact, TIFF’s success has helped to put Romanian cinema on the map, often starting as a launching pad for its belated 00s New Wave, a movement that’s still going strong and situates Romanian filmmakers among some of the best in the world. It makes me particularly excited for Romanian competition entries A Higher Law (Octav Chelaru) and Mikado (Emanuel Pârvu). Over four days I’ll be digging into what the festival has to offer, providing dispatches from the front-line of cutting-edge world cinema. Follow our coverage on Dmovies

TIFF Official Competition 2022

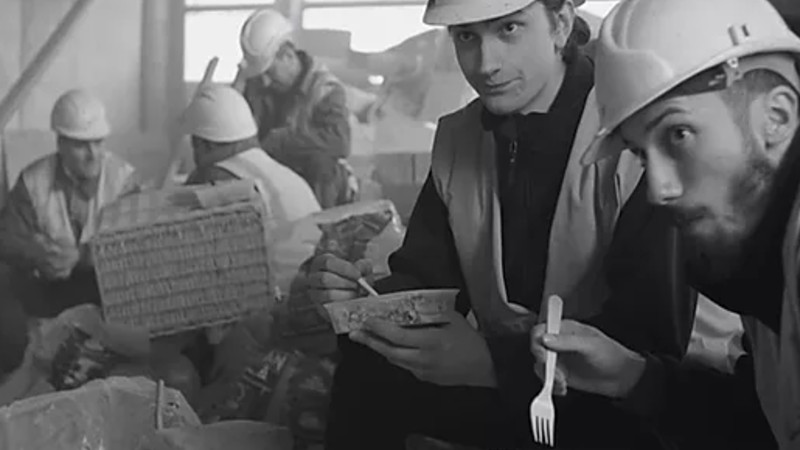

A Higher Law (Romania, Germany, Serbia, Octav Chelaru)

Babysitter (Canada, Monia Chokri)

Beautiful Beings (Iceland, Guðmundur Arnar Guðmundsson)

Feature Film About Life (Lithuania, Dovile Sarutyte)

Gentle (Hungary, László Csuja, Anna Nemes)

Mikado (Czech Republic, Romania, Emanuel Pârvu)

Magnetic Beats (France, Germany, Vincent Maël Cardona)

The Last Execution (Germany, Franziska Stünkel)

The Night Belongs To Lovers (France, Julien Hilmoine)

The Execution (Russia, Lado Kvantaniya)

Utama (Bolivia, Uruguay, France, Alejandro Loayza Grisi)

Pamfir (Ukraine, France, Poland, Chile, Germany, Luxemburg, Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk)

Documentary Competition

You Are Ceaușescu to Me (Romania, Sebastian Mihăilescu)

Bucolic (Poland, Karol Pałka)

Excess Will Save Us (Sweden, Morgane Dziurla-Petit)

Chanel 54 (Argentina, Lucas Larriera)

Brotherhood (Italy, Czech Republic, Francesco Montagner)

Mother Lode (Switzerland, France, Italy, Matteo Tortone)

Ostrov (Switzerland, Svetlana Rodina and Laurent Stoop)

The Plains (Australia, David Easteal)

Atlantide (Italy, Yuri Ancarani)

For A Fistful Of Fries (Belgium, France, Jean Libon and Yves Hinant)

Transilvania Film Festival runs from June 17th to the 26th, 2022.

T

T