This was by far the most eagerly anticipated film of the 70th Cannes International Film Festival. That’s because Michael Haneke’s last two films L’Amour (2009) and The White Ribbon (2012) both received the Palme d’Or. Plus he received other major prizes at the event for The Piano Teacher (2001) and Hidden (2005). And this also he kick-started his international career exactly 20 years ago with Funny Games.

The stakes were very high and the anticipation was such that the Festival and the director refused to provide a synopsis of the film. The only information available until two days ago were a couple of pictures, a short extract (at the bottom of this article), the cast and a very succinct clue as to what the film may be: “All around us, the world, and we, in its midst, blind.”

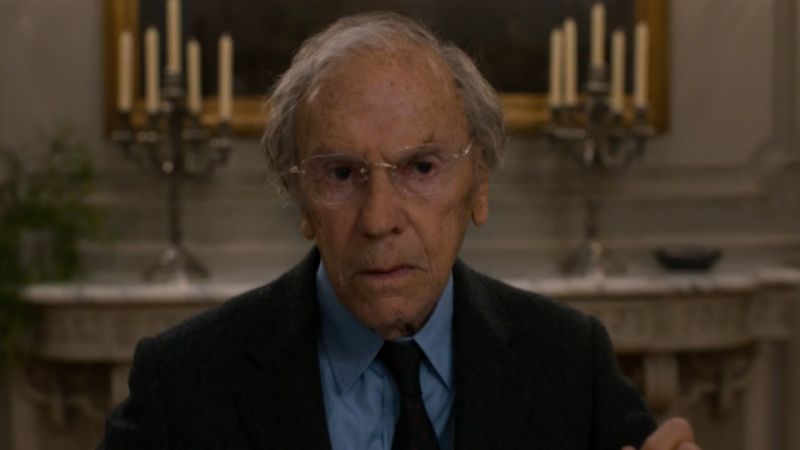

Haneke has delivered yet another majorly bleak study of Europe and human being. It tells the story of a bourgeois family based in Calais. Anne Laurent (Haneke’s regular anti-superstar Isabelle Huppert) runs the family business because her father Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant, pictured below) is too old and her son Pierre (Franz Rogowski) is too emotionally unstable. Her brother Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz) has a wife, a mysterious lover and two children, including 13-year-old Eve (Fantine Harduin) – whose mother is in hospital in a comma after a suicide attempt.

Death and suicide are central themes of the film, and they seem affect nearly every character in one way or another. Taking away your own life look like the only feasible solution, the only possible “happy end” to these deeply trouble people. They are engulfed in the mediocrity of their vulgar wealth, their loveless relationships and their futile routines. Huppert is extremely effective as usual, even if her character is one of the least complex in the movie. The little Fantine Harduin is the star of the movie, conveying a sense of misery and gloom that is guaranteed haunt you. Jean-Louis Trintignant is also very convincing in the role of the patriarch losing not just his desire to live but also his connection to the real world, as dementia begins to set in.

The first sequence of the movie will upset animal lovers, and I’m still not sure how it was done (whether the animal was harmed or killed in the making). One way or the other, it’s very realistic, and it sets the tone for the movie very early on: this is going to a deadly ride.

The socio-political commentary is also there. It is no coincidence that the film takes place in Calais, located in one of only two departments where Marine Le Pen beat Emmanuel Macron in the second round of the French presidential elections this month, and also where thousands of refugees are located. These largely unwelcomed aliens, who were often the subject of Le Pen’s rabid campaigning platform, make a very inconvenient appearance in a crucial moment of the film.

While effective as both a socio-political and emotional statement, Happy End feels a little trite if you are familiar with Haneke’s filmography and cinematic trademarks. It tries to recycle old devices without adding anything new. You will recognise the twisted sexuality of The Piano Teacher, the obsession with capturing banal actions on camera of Hidden and a very central element of Amour (which I can’t mention without spoiling the movie). In a nutshell, Happy End is a little too ambitious and not fresh enough.

Happy End was very well received, but it did not take the Palme d’Or home (which would be the Austrian director’s third). I wasn’t rooting for it. Haneke needs to come up with more original devices before taking receiving the highest prize in the film festival world for the third time.

This piece was originally written during the Cannes International Film Festival in May. The film premieres in the UK during the 61st BFI London Film Festival, taking place from October 5th to 15th. It is finally out in cinemas on Friday, December 1st.