Violence in cinema has always been the source of endless debate. When depictions go past the fairly anodyne — such as a climactic shootout in an action movie — and into the realm of the genuinely provocative, such as the horrific world of Cannibal Holocaust (Ruggero Deodato, 1980) or Irreversible (Gaspar Noe, 2002), they can provide a genuine shock to the system, provoking outcry and even calls to be banned. Such was the fate of A Clockwork Orange, adapted from the novel by Anthony Burgess, in which its protagonist Alex DeLarge wreaks ultra-violent havoc upon London with his fellow “droogs” without a single care in the world.

Now enjoying the status of a classic movie, it was met with fury upon its release in 1971. The Catholic Church rated it Condemned, meaning the faithful were forbidden from seeing it. Roger Ebert called it “an ideological mess” and “a paranoid right-wing fantasy” which only exists to “celebrate the nastiness of its hero” while Pauline Kael called it “an abhorrent viewing experience.” It was even blamed for copycat violence, including the murder of an elderly man and a rape where the accused sang Singin’ in the Rain as “Singing in the Rape”. Kubrick himself withdrew the film from public ownership, making it difficult to see in his native UK until after his death in 1999.

Balancing obsessive production design, kooky frames and a generous wide-angle lens, Kubrick drops us into a world that feels both alien and still contemporary. The boys talk in a strange dialect known as Nadsat — a mixture of cockney slang and mispronounced Slavic words —and roam around raping girls and getting into fights. Crucially, the root of Alex’s problems are never explained, Kubrick initially treating it all as a lark. He is never meant to be a psychological character, instead a case study for Kubrick to show off his unique and abundantly self-satisfied style. Additionally, the soundtrack, courtesy of huge classical hits such as Beethoven’s Ode To Joy, Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie and Moog Synthesiser compositions by Wendy Carlos, gives it a sheen of the sublime, making Alex’s actions feel rather seductive.

If A Clockwork Orange only consisted of its first half, it could easily be dismissed as Kubrick depicting violence only for the mere sake of the thing in itself, pushing the limit of what can be seen on screen. Yet the second half takes us into deeper philosophical territory, with Alex, now a convicted felon, treated to a brutal bout of reprogramming. He is forced to watch horrific acts, including endless rape scenes and even clips of Nazi Germany, all scored to his favourite songs. Once he is let free into society, he shows no interest in violence or sex or even music, eventually becoming a similar victim to the violence he once released.

These two halves of the film, almost perfectly centring around the iconic cinema scene, are in direct contradistinction with each other, showing Kubrick’s fondness for bifurcating films between two distinct parts (most clearly seen in 1987’s Vietnam drama Full Metal Jacket). In its second half, A Clockwork Orange becomes a commentary upon violence in cinema itself — its meta quality stressed by those horrific film clips Alex is forced to endure — and how context can change the meaning of violent acts completely. The violence in the second half is nearly just as shocking and brutal as the first, only this time, we’ve finally identified — despite his numerous faults — with the former monster. He may be a terrible person, yet the way he is treated — unable to fight back due to his reprogramming — makes us pity him, like a once violent dog that’s been completely neutered and drugged into a shadow of its former self.

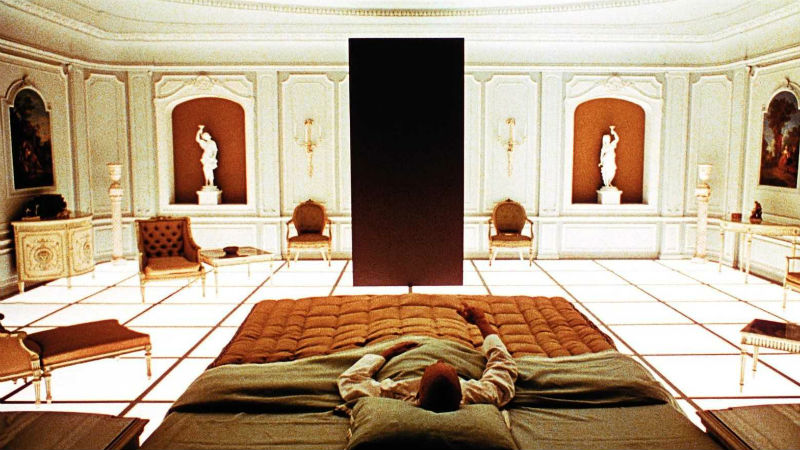

Of all Kubrick’s major films, A Clockwork Orange is easily his less subtle — with a broad (and perhaps simplistic) philosophical point about the horror of the state being worse than any one individual — but its more interesting for the ways he can so easily manipulate the audience’s sense of empathy. It seems he was only too aware of the easily-drawn message of Anthony Burgess’ original novel, Dostoyevskian in the way it starts with horror before moving towards a classic Christian message of redemption. Instead Kubrick famously lets Alex off, ending with a fantasy of him raping yet another naked woman, totally surrounded by adoring spectators in bizarre Edwardian gear. It’s as if to remind us of the artifice of his creation and cinema in general. Sandwiched between the sublime 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and the beautiful Barry Lyndon (1975) – films that both end on more purposeful and enigmatic notes – it can feel like somewhat like a relative low-point. But the lessons it teaches us about violence in cinema seem to have come to the fore the last year, especially when it comes to the world of violent arthouse film.

Take Climax (Gaspar Noe, 2018) and The House That Jack Built (Lars Von Trier, 2018), both films made to provoke and push buttons by indulgent auteurs relentlessly plundering from their own filmography. Two similar yet crucially different scenes stand out for me. In the former a child is locked away and left to die, while in the latter the eponymous Jack shoots a child in the head and uses the body for taxidermy. Both feature a young and helpless child dying, yet I laughed at the former and nearly left the cinema in protest at the latter. Pitting the two cases side by side makes one reflect that its not the act itself that has any meaning. It is the way it’s presented — brutally funny in Gasper Noé’s case (presented off-screen) and unrelentingly awful from Lars von Trier (shown in all its horror)— that makes us view it in a particular way.

Likewise, I thought I was done with serial killer narratives after The House That Jack Built, but found Fatih Akin’s The Golden Glove (2019) – a film some referred to upon its Berlinale premiere as a complete abomination – to be an utter delight, showing how complicated the relationship we have with violence can be. Watching A Clockwork Orange – a moral quagmire or a mess depending on how you look at it – once again reminds me that context is everything. Whether its style, personal feeling and experience or how much we are or aren’t shown, the way an act is presented or the way we look at an act can change its meaning entirely. Forty-eight years later, A Clockwork Orange still remains the ultimate case in point.

A Clockwork Orange is back in UK cinemas on Friday, April 5th, almost five decades after its original release, thanks to the BFI. Watch the film’s brand new trailer below: