QUICK AND DIRTY: LIVE FROM BERLIN

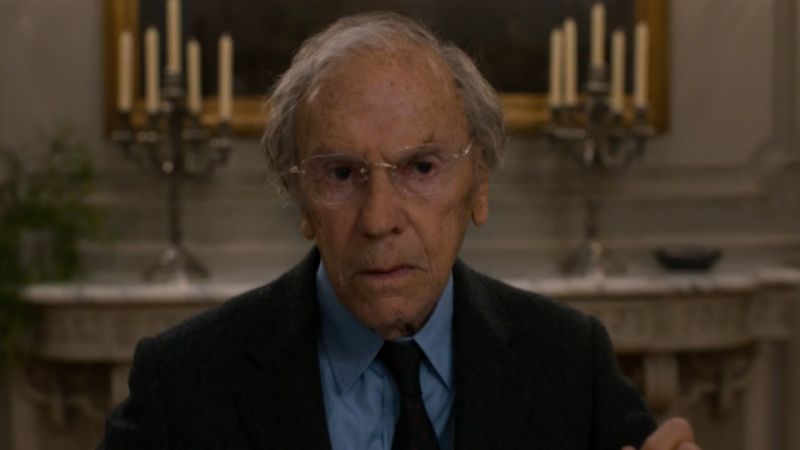

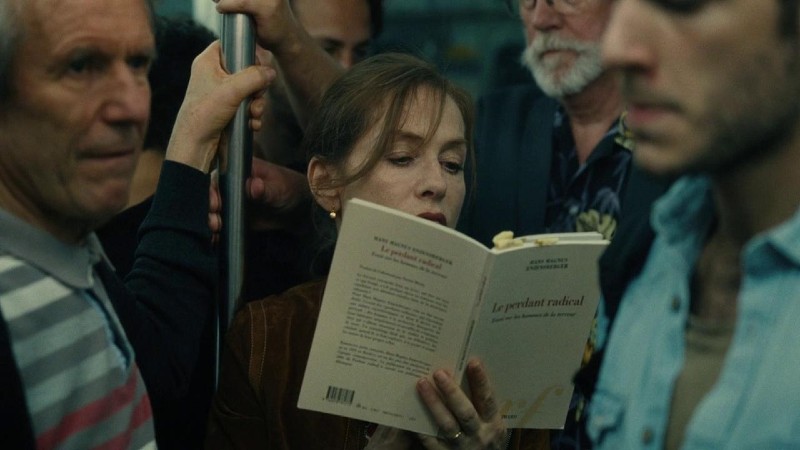

Isabelle Huppert and André Téchiné are two powerhouses of French cinema. They only worked together once, 45 years ago, in The Brontë Sisters. This means that the expectations are high, at least for this humble film journalist. Unfortunately, when we set the bar so high, the odds of disappointment are equally bis. My New Friends is an unsatusfactory film, with plenty of good intentions, most of them left unfulfilled.

Huppert is Lucie, a police forensic expert. Her husband Slimane, an African immigrant, also a policeman, committed suicide due to work pressures. As she grieves, a young couple moves next door, with Rose, their 13-year-old daughter. Lucie gets closer to them, without knowing that Yann (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, from Robin Campillo’s 120 BPM, from 2017), the husband, is an anti-police activist and artist with a long criminal record. The main subject of the film is Lucie’s moral dilemma between her professionalism and her desire to help his family. Huppert’s character runs a a lot: it seems to calm her down and keep her fit. At 71, the French actress indeed remains very fit.

This is a good premise that could have provoked some interesting discussions about police morality and ethics as well as Yann’s motivations, but unfortunately Téchiné seems more interested in devising unexpected twists and turns. At the ripe age of 80 years, he seems to be in a rush. The film is very fast-paced. This gives the impression that Téchiné is not really interested in getting inside the psychology of the individual characters. A little trivia: .My New Friends features is a special appearance of Stéphane Rideau of Wild Reeds He plays a police chief.

Lucie’s dilemma is superficially examined. Huppert’s trademark detachment and calculated coldness in her acting her personal drama even a little more inscrustable. Téchiné has some very emotionally affectig dramas such as My Favourite Season (1993) and Wild Reeds (1994). This time, he feels a lot more distant from his characsters. It’s only in the second act that it all slows down a little, and Huppert does what she does best: she gets passionate and shows her vulnerability. Lucie gets very attached to Julia (Hafsia Herzi) Yann’s wife, and to their daughter Rose (Romane Meunier). But once the police discover she is helping Yann – who is actually under house arrest – and capture him at his house, Lucie fears she will lose her new friends. It’s a breath of fresh air in this mostly gritty story. Without giving away any spoilers, it suffices to say that the closing is satisfactory.

Let’s all hope Huppert and Téchiné Collaborate once again. Neither one has another 45 years to wait!

My New Friends just premiered in the Panorama section of the 74th Berlin International Film Festival.