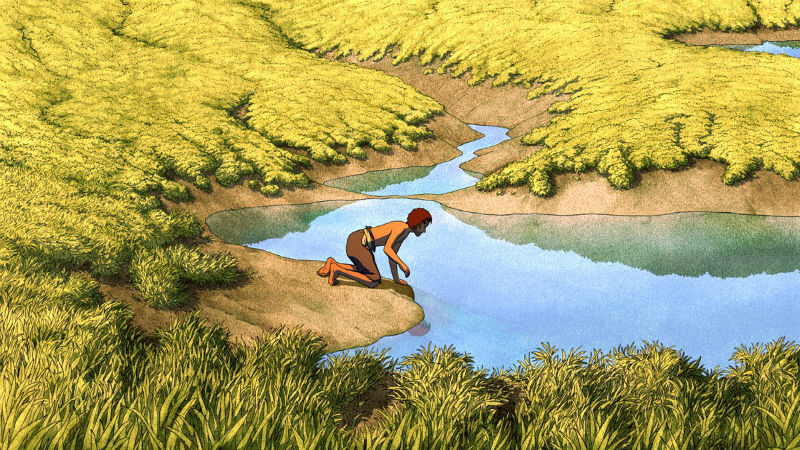

Filming in the Amazon is no easy task: there are more eyes in the jungle than there are leaves. There is life on every surface and the life vibrates and does unexpected life-like things in the jungle. The jungle sees, the jungle hears, the jungle eats, the jungle screams and whispers and moans and gossips and transmits information through a vast rhizomatic network of cellular nodes. Filming in the jungle is no easy task.

This way the jungle quickly finds out you are there. It knows what you do and what you like, but mainly it knows what you don’t like. It knows that your crew from the city doesn’t like the jungle, because city people want to be apart from the jungle. But for the jungle there is no outside. It makes everything a part of itself. Including you.

We shot Icaros: a Vision at an Ayahuasca centre in the Peruvian Amazon about an hour outside the city of Iquitos, where 30 years ago Werner Herzog shot Fitzcarraldo. We shot there for five weeks straight (plus a week in town), with a cast and crew that at its height reached 40 people, a handful from the US, most from the capital Lima and a number of people who lived at or near the centre. Compared to what some doc crews go through ours may have been a comfy shoot. We didn’t track jaguars or sleep in tents. For its regular foreign visitors, the somewhat dilapidated centre had a number of tambos – Amazonian bungalows – with hand-sawn wooden beds.

We bought a load of new Chinese mosquito nets from the market. And though the centre’s old mattresses were cratered like a lunar landscape and occupied by unseen and unknown bugs, at least we had mattresses. Still, it’s not easy keeping city people happy with no running water, and the catering done on an open fire – an open fire indoors, under a thatched roof, in a ‘kitchen’ that has no fridge and no sealed storage. The cooking was done by the amazing Gloria, who was born in a canoe, did the catering for the original Fitzcarraldo, and carried a machete on her motorbike. But even she didn’t escape unscathed. A week in, she was hospitalised with burns on her chest and neck. Fortunately she was fine and back on the job a few days later.

Very quickly, the jungle found out about the kitchen. The Amazonian saying is, when ants come into your home, change homes (or don’t keep unwrapped protein bars inside your mosquito net). We had ants, but they weren’t the big problem. Jungle rats were. After dinner, our kitchen became their kitchen. Which is fine, in principle, except in that region the rats seem to carry leptospirosis, a potentially deadly bacteria they deposit wherever they urinate and defecate (i.e. wherever they eat, i.e. our kitchen).

That is why we got very worried when one of our New York crew reported with alternating cold sweats and fever. He was hospitalised for several days before being released without a conclusive diagnosis, though the bets were on leptospirosis. Whatever it was, it involved non-benevolent bacteria since antibiotics seemed to have mended him. He wasn’t the only one. Three other crew members were hospitalised with a range of symptoms without a precise diagnosis – Malaria? Stomach bug? Leptospirosis? Fatigue? Amazonian poison ivy? Eventually, everyone came out alright, but this sort of thing sucks out a lot of energy.

.

How do I protect myself?

So insurance is a good idea. For everything you can possibly think of and a few you can’t. Also, if you have a friend who is a doctor, specifically a doctor who is willing to show up in the jungle for no meaningful compensation, on his way loot a Western hospital for emergency medical supplies, dispense antibiotics on a daily basis to fight off potentially deadly diseases, dispense advice on psychoactive substances and keep track of the crew’s laundry too, we definitely recommend you take him or her along. Probably you should consider paying for the airfare.

Clearly, a shoot involves the disruption of a pre-existing ecology, and therefore also an opportunity for the rise of a new one. Here is how the jungle co-evolved with us. Crew member A feared rats, B feared spiders, C feared bats, D feared snakes, E hated frogs. Rats attacked A. B woke up every night with tarantulas crawling above her mosquito net. A bat landed, wings sprawled, on C’s face. Snakes crossed in front of D on the first night and the last. E came back from the bathroom in the middle of the night to discover her bed covered in blood, the blood of a pregnant frog, crushed somehow on her sheets. That is what the jungle does to you. It is its way of making you a part of it. If it works, you won’t have your fears anymore. But it doesn’t work for everyone. So you have to be ready to book a hotel in the nearest city where they also serve beer.

The jungle hides things too. It hides guerrillas, drug dealers and water buffaloes. You don’t want to bump into the last two, especially if you have lots of camera gear. Since no roads lead from the capital into Iquitos, our equipment, including a generator, was shipped up the Ucayali river on a barge, on two trucks with four armed men. It was all supposed to arrive at the site four days before the start of the shoot. The camera came in with the camera crew on a plane from Lima, and the lenses, we brought with us from New York. Everyone was beginning to stream in. The Ayahuasca center in the jungle was rising to that pre-shoot hum, everyone flipping through the schedule, waiting for the first call to ‘action’. Except we had no tripods, no lights, no generator, no gear. It was all on a couple of trucks on a barge somewhere on the river.

Word from the transport company was that the river marine had stopped all traffic for large boats because the river was too low. We had to wait for the levels to rise. The shoot wisely had been planned for the non-rainy season, but we had never accounted for this contingency. We waited another day. For rain. And another. Still nothing. The good secular crew from the city was about to ask the Shipibo shamans to do a rain ceremony. The local producers finally went around the barge company to contact the truck drivers who were on the boat, waiting to be released. Apparently, there was no water level problem. The problem was that the barge had been hijacked along the way by smugglers and a bunch of the trucks had been stuffed with cocaine. The marine had gotten whiff of it and impounded the barge. Thankfully, we didn’t need to wait for the rain, but we hadn’t planned for this contingency either.

We began the first couple of days of the shoot without proper gear (if you buy some amazing inexpensive light weight battery-operated LED fresnels – I say Fiilex – they can save your ass in such situations, as well as other ones throughout the shoot). On day 3, we heard that the marine had released the barge and our trucks with it. It was scheduled to dock into a neighbouring port the next evening. To gain a day, our Peruvian partners, who felt that the jungle had cursed the shoot, sent out the single production truck to meet the boat in Nauta, one port down river from Iquitos. This way we could start day five with proper gear.

Our commando team left the centre at the end of the shoot day, boarded the barge at midnight armed with flashlights, swiftly unloaded the crucial gear and was back on the road by 1:25. That road is the only one leading out of Iquitos. And, 100 some kilometers later, ends in Nauta, a closed circuit. It is also, mile for mile, dollar for dollar, the most expensive road constructed to date in the world. At 2:00, half way between the port of Nauta and the centre, a big grey water buffalo began to cross that expensive, paved, asphalt road. Jungle lined both sides and the moon was nowhere to be seen. There were no white lines dividing the road. It was all one indistinct greyscape into which the truck moved quietly until it hit the water buffalo smack in the ribs. The buffalo mooed (or whatever sound buffaloes make) and walked off into the jungle. The truck crumpled on its axles and we lost it for the duration. It was a big buffalo. No humans were hurt, but the lesson was that it is not a good idea to have a tired crew commandeer a drug-smuggled barge and drive back through the jungle at 2:00 in the morning.

.

The panacea for all modern ills?

One last thing. Ayahuasca. You’ve probably heard of it. Its main job is to teach you lessons. It’s a teacher plant, a vine that grows in the Amazon. It gives its name to a hallucinogenic or medicinal brew that has made its way out of the Amazon into the rest of the world, including Brooklyn. And Moscow. And Paris, London, Rome, Cairo, probably Shanghai too. It’s everywhere, even in the New York Times so you can easily find out about it. But it’s not so much that Ayahuasca has made its way out; it’s that this is just another way the jungle is taking over again.

That may sound optimistic, of course, because the jungle is also under deep threat.

The lungs and the roots of our biosphere, the jungle is truly powerful and along with said biosphere may well find a way to survive our best efforts to destroy it for instrumental purposes. But we can’t underestimate these other equally powerful forces out there, with their own networks and flows and ecologies – the ecologies of capital and consumption. Some loggers in the region obviously do turn a profit, but these are always subject to market fluctuations; to hedge their bets, then, they often also do double duty as fronts for cocaine smuggling. They stuff bags of coke into the tree trunks and ship them off. Effectively, they hollow out the amazon to pack it with cocaine for consumption in Silicon Valley and Wall Street.

Peru has now surpassed Colombia as the leading exporter of cocaine. On top of that, there are the oil and gold companies, and waste management companies. If the loggers and timber companies are cutting down trees to make yachts and mansions and paper products in the big global metropoles, the waste companies are buying cheap land in order to dump toxic waste brought back from those very metropoles, and the oil and gold companies are there doing what they generally do best, making a big irredeemable toxic mess.

These are just a few things you should know if you want to shoot in the jungle. And, yes, don’t forget the bug spray…

Click here for our review of Icaros: A Vision.

Nevermind Wes Craven: the hills are not the place where you are most vulnerable. Find out more and learn some very useful tips from those who passionately embraced the challenge in the Peruvian Amazon. DMovies held three screenings of Icaros: A Vision in London between July 5th and 7th.