Firstly, Mutafukaz (as MFKZ was originally named) is a Japanese animated feature made by the French for the French market utilising Japanese animation expertise (the version playing at the London Film Festival is French with subtitles, though the end credits suggest there might also be an English language version), secondly a very French, lowlife, dystopian action movie to rank alongside the live action likes of Nikita (Luc Besson, 1990) and, particularly, District 13 (Pierre Morel, 2004) and thirdly an adaptation of a French bande dessinée, the director Guillaume Renard having penned the original in comic book form under the name Run.

The animation medium allows the piece to completely design its images and environment from, as it were, the blank page/empty screen upwards and the results are fabulous. Japanimation company Studio 4°C previously worked on such high profile anime productions as SF portmanteau Memories (Katsuhiro Otomo, 1995), avant garde pop video Noiseman Sound Insect (Koji Morimoto, 1997) and fan favourite Spriggan (Hirotsugu Kawasaki, 1998) to name but three (others are name dropped in the trailer) and pull out all the stops here.

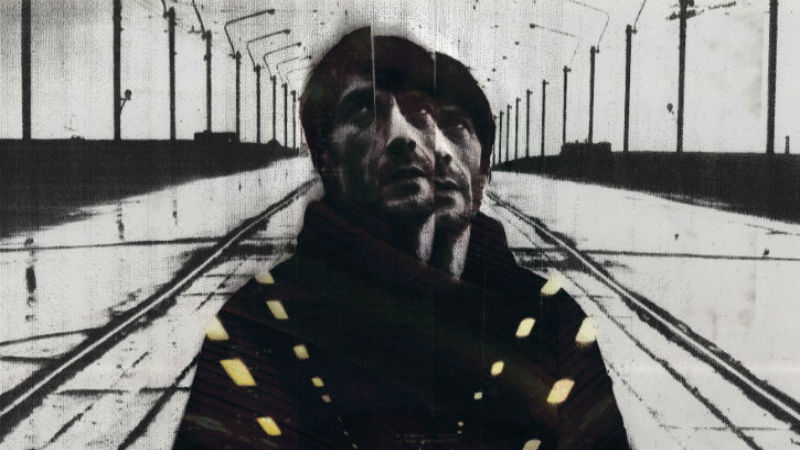

(Ange)lino is a small, young, black guy vaguely resembling Marvin Martian without the helmet and struggling to survive the mean streets of Dark Meat City (“DMC, as in Desperate, Miserable, Crap”) where he rents a roach-infested apartment with his mate Vinz whose head resembles a human skull, bare bone, no flesh, column of fire permanently burning on top. Lino can barely hold down a job for more than a few days.

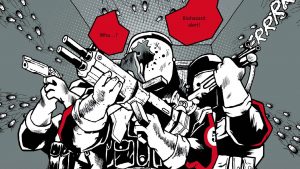

We first meet Lino on a pizza delivery boy gig which falls apart when the sight of a pretty girl causes him to have a bike accident. Unemployed, Lino and Vinz are visited by their nervous liability of a friend Willy. As the three cruise around in a car, Lino notices a strange phenomenon inspired by They Live (John Carpenter, 1988): people who cast shadows belonging to creatures not of this Earth. Meanwhile, a mother with her baby in her arms is being hunted by mysterious, gun-toting men in black suits led by one wearing a white suit. Before long, they’ll be after Lino and Vinz too.

The film rattles along at a rapid pace through urban malaise, gangland shoot-outs and conspiracy theories, in passing presenting a squalid environment that could stand in for the seamier side of any number of real life cities. Designed in glorious, eye-popping colour and with a hip hop sensibility referencing Grand Theft Auto and more, it never lets up for a moment.

Although the production values have anime written all over them, with key fight scenes shots sporting familiar tropes of that medium, Renard’s Francophile sensibilities inject a whole other aesthetic and indeed feel to the proceedings. It’ll no doubt be huge in France, but it’s an impressive work which transcends its national culture and deserves to see a UK distributor taking a chance and giving it a proper release here too. I could never imagine London Transport accepting posters bearing the film’s international title, though. Which is why the new English language title MFKZ makes a lot of sense.

MFKZ played at BFI London Film Festival 2017 as Mutafukaz. It’s released in the UK on October 11th. Watch the 2017 international film trailer and the new 2018 English language film trailer below: