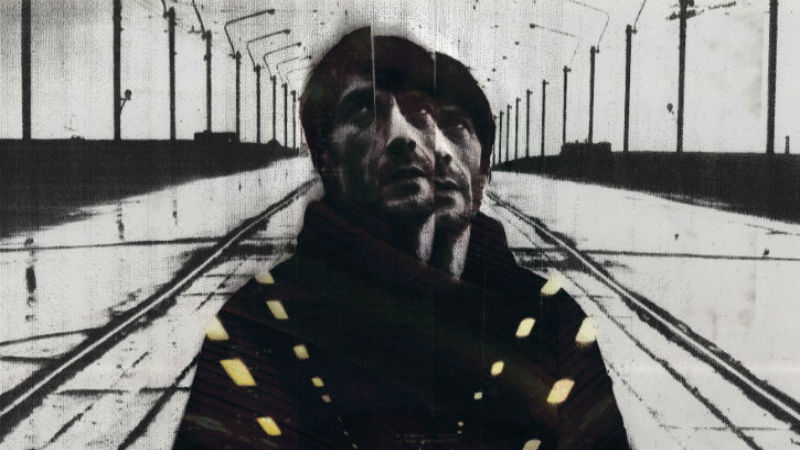

Almost nine years on from his faux documentary, The Conspiracy (2012), director Christopher MacBride returns with the Canadian psychological and sci-fi thriller Flashback. Fred Fitzell (Dylan O’Brien) stands on the precipice of adulthood. In a committed relationship with his long-term girlfriend Karen (Hannah Gross), he faces the pressure of a new corporate job, and his mother’s ailing health. When a chance encounter with a man from his youth results in terrifying flashbacks, Fred tries to piece together the fragmented memories of taking an experimental drug called Mercury. Becoming obsessed with finding out what happened to Cindy (Maika Monroe), a girl from his High School who went missing, the struggle to hold his life together threatens both his relationship and his job.

As with The Conspiracy, which sees two filmmakers go in search of their subject, a conspiracy theorist who mysteriously disappears, the motivational drive of Flashback’s story is also to discover the fate of a missing person. MacBride shifts his focus from the external to the internal. In as much as Fred becomes obsessive about what happened to Cindy, the story is as much about the choices and possible outcomes that have shaped his life. If the characters are searching for one another or themselves, it’s a reflection of a filmmaker whose developing his own creative language and identity.

An enjoyable hyper-energetic piece of filmmaking, MacBride flirts with the idea of what it could mean if we control our sensory responses. Cindy says to Fred after taking a weaker dose of Mercury, “There’s so much to explore if you don’t give in to the pleasure.” It’s an intriguing idea that brings definition to the story, underpinning it with an intent to develop ideas and themes. Questions of what lies beyond our perception, and the hidden mysteries of the mind are tantalising, offering any storyteller compelling, creative and entertaining material. Unfortunately the limited execution here leaves us to sense a debilitating sparseness to the storytelling, and the feeling that it gets lost in its own rabbit hole.

In spite of these qualms, MacBride is able to engage us with the emotional hook of Fred’s relationship with both Karen and his mother, portrayed with a sensitivity and gentleness, even if guilty of being a little saccharine. This is offset by the less optimistic idea of our shared existential crisis.

Sitting on a rooftop overlooking the city at night, Cindy tells Fred, “I don’t want to be like them. Locked in a prison that they’ve forgot that they’re in. Look at all of them, running around, pretending to know exactly who they are and why they’re doing what they’re doing.”

It’s a clichéd thought, yet that doesn’t make our shared existential crisis any less true. During the pandemic the idea of “normality” has been on our minds, and we have a choice. We can return to the “old normality” or seek out a “new normality.” Cindy’s words and Fred’s piecing together his fragmented puzzle feeds into the dilemma that occupies our present day reality.

The idea of sensory control, and the planes we can explore that lie beyond our perception are only a dream. For now we must use imagination to ponder these possibilities. It’s a grandiose idea that elevates the discussion about “normality”, to the hypothetical of, what if we could expand the possibilities of the human experience?

MacBride synchs his film with the timely question we should be asking ourselves: what do we want our collective futures to be? He retreats from any grand declaration to instead offer a simple thought. Fred’s fate proposes the idea that each of us has to create a space for ourselves. It’s one that should fulfil our needs to feel a sense of belonging, meaning and purpose, even if someone sat on a rooftop dreads the thought of being like us. We cannot control our collective “normality”, but we can control our personal sense of it.

Flashback is out on Sky Cinema and NOW on Friday, September 30th. On IMDB TV on Monday, January 3rd. Also available on other platforms.