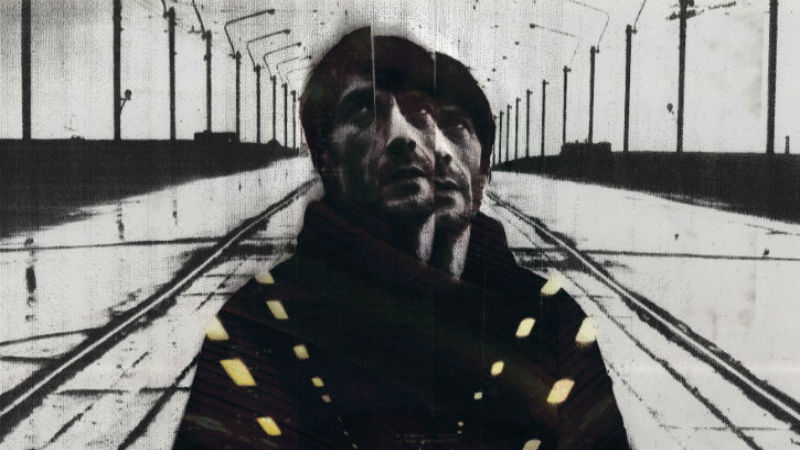

Holidaying in Cambodia with Isaac (Ross McCall), Ben (Kelly Blatz) is getting over his father’s death. He runs into and falls for fellow Bostonian holidaying abroad Amber (Jenny Boyd) who after getting rid of him as fast as possible when he first attempts to pick her up, makes amends and comes on to him in a bar, where he’s hanging out with male friends.

She takes him back to her room for an unexpected topless exposure, a scantily clad embrace and no actual sexual congress.

The next day, Ben spots Amber having a spat with another Westerner and quickly gets into a fight with the latter – which situation swiftly escalates as Ben and Amber are walking away and the other man snatches a meat cleaver off a local and races after them. Cue a breathtaking chase through various narrow back alleys. Amber drags Ben in through a doorway and to his surprise, in a scene that would probably have made Hitchcock extremely happy, unbuttons Ben’s belt and gives him a blow job. It’s difficult to believe it’s the same woman.

And of course, that’s the twist – Amber has a scar indicting she was separated from her then twin at birth: she lived, her twin died. Yet lurking within Amber is another entity… her twin sister?… or something else?

One odd sequence has Amber sexually assaulted in one location (buttons being undone by an unseen force as she writhes and squirms, clearly having an unpleasant experience, while elsewhere in his car the meat cleaver-wielding assailant from earlier is locked in his vehicle – again by unseen forces – and subjected to loud music bursting from the car radio and subjected to an unpleasant fate. But that doesn’t prevent him from later spotting Ben at a local dance bar, getting him drugged (with Amber’s help? – it’s not clear) and attempting to exact revenge on Ben later on.

As Isaac and friends head off North and Ben stays behind, Amber’s behaviour becomes increasingly polarised, with the film throwing in for good measure her epilepsy and a Cambodian couple running a local medicine shop.

It’s a funny mixture of a white man’s Western view of Cambodia – beautiful Western females to sleep/fall in love with, evil spirits, medicinal hocus pocus and more, an outsider’s view of the culture rather than an insider’s.

The script provides a number of elements that might explain what besets Amber and while the finale wraps everything up neatly, a number of the elements present never really lead anywhere. The characters are believable and the performances adequate, the whole thing working well enough as a once only view on download without being anything truly memorable. The result is an efficient horror that succeeds in item modest aims but has little to say beyond satisfying its (white? male?) audience as an efficient yet vacuous exercise in generic horror.

Hex plays in the Raindance Film Festival. Watch the teaser swimming pool scene film trailer below: