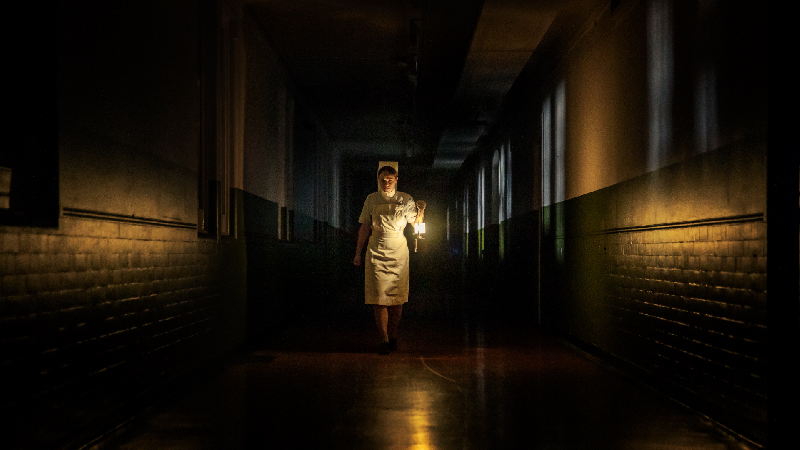

Director Ben Charles Edwards’s Father of Flies, is centred on Michael (Keaton Tetlo), a young boy frightened of his stepmother, Coral (Camilla Rutherford), discovers a supernatural presence lurking in the house.

Following his creative feature début Set The Thames on Fire (2015), Edwards combines naturalism and a surreal style in his visually striking sophomore feature.

In conversation with DMovies, Edwards discussed his haunted childhood home and the need to own the responsibility of being the storyteller.

…..

Paul Risker – I’ve read that the story is partly based on childhood experiences, is that correct?

Ben Charles Edwards – Partly, yeah. A good friend of mine Dominic Wells, was the editor of Time Out when he was very young. He’s a terrific writer and he wrote some of my first films. When I told him I wanted to write something I could in a sense own myself, he said, “Ben, make it about something you know.” I love horror, and so it was the connection of how I draw from something I can relate to, and feed into the horror genre.

I was on a train in Morocco, going from Fez to Marrakesh, and I sat there and turned out all of the beats for the story on this six hour train trip. I thought that’s actually quite good, I’ll probably invest a bit more time into it.

It’s like everything, I never set out to make films; I started out as a portrait painter and then a photographer. I’ve just done what feels right, and this story did. It’s about a family that has gone through a divorce and the children are at the centre of it. While that’s not a huge part of my life, it just so happens to be an interesting beat that I thought I could draw off.

PR – Was the experience of divorce the only personal beat you drew from?

BCE – … I grew up in what I believed to be an incredibly haunted house. It was on the edge of Woking and it was built on the old cemetery, on some unmarked graves we later found out. It was old marshland that was sold off, and I know it sounds a bit nutty, but I do believe it was a haunted house. There were certainly unexplained and quite terrifying things going on there.

I had five brothers and sisters, many of them were teenagers at the same time. There’s a lot of tension and emotion running through a house like that, so sometimes you wonder if it’s something we manifest and create ourselves, or if there is another entity in the house?

PR – What we’re talking about here is the question Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1960) asks – is the house or are the characters the ones that are haunted?

BCE – Perhaps it’s both, and we feed into the machine, or into that emotion, and that’s how we manifest the emotions from past lives lived in those houses. We always think of it as our house, and it’s really not. This is England, and the majority of homes that people live in, certainly outside of London, will be houses that many people have lived in before. They’re little vessels of time and we’re just one little moment, a little part of its story, not the other way around. So it doesn’t surprise me that we feel the other stories that have lived their before us.

PR – There’s the idea amongst filmmakers that there are three versions of the film – the film that’s written, the film that’s shot and the film that’s edited. I recall Pablo Larraín telling me that the film is discovered in the final cut. Would you agree, and was Father of Flies a journey of discovery?

BCE – Films do take on three stages and a great editor is a storyteller, or certainly a great problem solver and storyteller. Of course you aim to get what’s on the page, and you hope what’s on the page will work perfectly well in the edit suite. Sometimes it doesn’t and there are adjustments that have to be made.

With this film, the concept was quite strong in my mind from the beginning, and all of the beats felt strong. Without giving too much away to the reader, those beats needed to be precise, otherwise the twists wouldn’t work. You couldn’t veer off the script within it’s structure, and like any film, the foundation that you lay at script stage is everything. An old friend of mine tweaked it and padded out the characters, and that was vital. It brought something to it the actors enjoyed, and to be honest, many of the performances were improvised.

The actors knew where they were going with the scene, they knew how the script had to hang together in its beats, so I just let them go with it. I’m not someone that over-directs. It takes longer to go through improvised scenes in the edit, but you do find some natural magic and that’s something I wanted to bring to this horror film. Hopefully the performances demonstrate that.

I went through three different editors [laughs]. They were all talking to one another, so it was part of the plan, and each editor brought something new. We had someone that looked over the dailies and pulled out the best options, and then we had someone that pulled together the structure in accordance with the script. We then had someone who said, “Ben you’re wrong, give it to me and I’ll clean it up.”

PR – Does improvisation create a space for the audience to enter the film, and can the naturalistic performances that support this?

BCE – It depends on the movie. Some directors and some scripts lend themselves to sticking to those step aged elements. When you look at a movie by Wes Anderson, it would be hard to assume that any of that’s improvised. Then you look at the kitchen sink dramas by Mike Leigh, and you assume that a lot of that is improvised. They’re different approaches to different types of filmmaking and emotions. It depends on what you’re trying to achieve.

I’ve only made four movies and I’m still learning, and rightfully so. We should all be on that journey to continuously learn and find out what works best for us, the story we’re trying to tell and how we’re going to tell it. I enjoyed the approach to Father of Flies. I let the actors have a little freedom because unless I am the best bloody writer, which I’m not, you’re going to get a more natural performance, and something more interesting and human.

When you’re trying to create a horror, you want to connect with the naturalism, and especially in a film like Father of Flies because there are elements that are quite stylised. It was a worry about keeping it grounded to some degree, so the audience can relate, be scared, and believe the scenes, the characters and the emotion. For a film like this it helps to improvise and keep that natural, giving the actors the freedom to create the play ground, by giving them the stage and saying, “Knock yourselves out.”

PR – Does the collaborative nature of filmmaking, and if you say the editor is a storyteller, challenge the validity of the auteur theory?

BCE – … I’ve never considered the auteur question too much. When one is the writer and director, it’s pretty clear who the author is. When a director is executing someone else’s script, they can take a script where they want, so in that sense they’re the auteur because they’re inspired by the script.

I’ve watched movies by great directors, and when I’ve met them and looked over the original screenplays, you realise how they went off script. In that sense, it’s their vision to execute the story.

In answer to your question, the director is the auteur, providing they’ve taken on the responsibility and grabbed it by the balls, and made it theirs.

Father of Flies has just premiered at Grimmfest and played at the Raindance Film Festival.