QUICK SNAP: LIVE FROM TALLINN

Fiona Shaw is a national treasure. As the terrifying matriarch at the heart of Kindred, she shrieks and scowls, scoffs and shocks with venomous glee. Occupying a central space in this British pregnancy horror, she reminds us that she is one of the best actors working today.

An indication of her character Margaret’s entitlement comes quickly into the film. When she is told by her son Ben (Edward Holcroft) and girlfriend Charlotte (Tamara Lawrence) that they are moving to Australia, her reaction is of pure disgust. How can they leave her and her enormous manor behind? But why wouldn’t they want to leave? She is a dark and difficult woman, constantly doted upon by her “nice guy” stepson Thomas (an excellent Jack Lowdon).

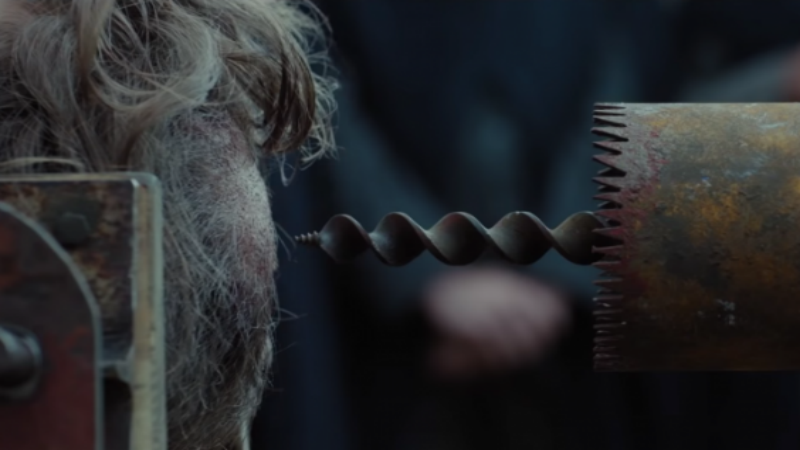

Things suddenly change when veterinarian Ben dies in a horse-related accident. Charlotte, suddenly pregnant despite being on the pill, blacks out in the hospital and awakens in this large, ancestral home, replete with long corridors, creaky floorboards and various other Bric-à-brac. She wants to use her phone. It’s broken. She wants to go back to her home. It’s been foreclosed. She wants to go to a hospital? Thomas can take her… No matter the reason, Charlotte finds herself unable to get out or contact anyone.

Charlotte is black but her race is never mentioned in the film. Nonetheless, it seems to be an exploration of the well-documented ways Black women are more likely to be disbelieved than white women, especially in a medical setting. Charlotte is constantly being gaslighted, from the small things — like complaints about dizziness being waved away— to the large, like the amazing moment when she tells a nurse that she is being kidnapped to remarkable indifference. There is also the fact that these large legacy homes across the UK are notoriously white spaces, making Charlotte a constant stranger despite technically being part of the family.

While engaging in the odd symbol here and there — the reappearance of the horse shot like its come straight from a Lloyds commercial, and a flock of birds straight out of Hitchcock — this horror leans more family thriller than supernatural. And unlike many big theme horrors that have come out in recent years, which lean on metaphor and feeling more than good old-fashioned storytelling, debut director Joe Marcantonio has a great eye for set up and pay-off, making it a remarkably entertaining movie. A fair point can be made that the hereditary theme isn’t really explored at all, but it’s not much of a big deal when the film is just this much fun.

With constant twists and turns, delightful red herrings and moments of genuine suspense, Kindred has ounces of flair. Supported by three remarkable performances, including Tamara Lawrence’s steely resilience, Lowdon’s skin-crawling creep act, and Fiona Shaw’s scene-chewing monologues, and this is easily the best British horror of the year. Expect a warm reception back in Britain.

Kindred plays as out of competition in the First Feature strand at Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, running from 13th to 29th November.