Virginia Woolf’s novels are wholly original, dazzlingly sensational texts that sing right off the page, able to conjure up whole worlds, smells and sensation through the innovative use of stream-of-consciousness. A woman able to carve out a literary career in a world in which men still had all the advantages, she is a true feminist icon and one of the greatest writers of all time.

A large part of her later success is down to the inspiration of Vita-Sackville West, her friend, confidante, fellow writer and lover. Famously Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992), featuring a gender-shifting protagonist, is based on her cross-dressing style. Like Scott and Zelda Fitzgerland, or Henry Miller and Anäis Nin, this is one of the great literary relationships, and ripe material for cinematic adaptation.

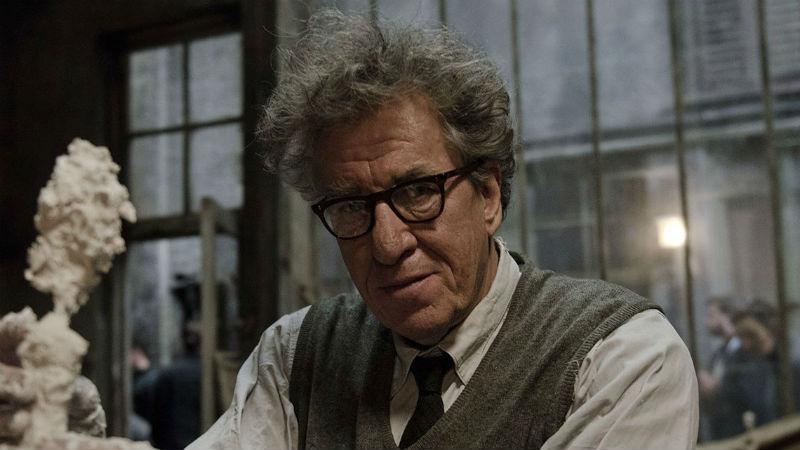

Literary biopics can go one of three ways. In the first two, they either take inspiration from the writer himself, and ape his style, such as in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998), or have a completely different auteurial approach, like Alexei German Jr’s melancholic look at Sergei Dovlatov’s life in the eponymous 2018 film. Yet too many take the third route, in which the major events of a person’s life are simply lifelessly recounted. Vita and Virginia is perhaps one of the most egregious examples of this, yet considering the specifically lesbian subject matter, even more of a greater disappointment.

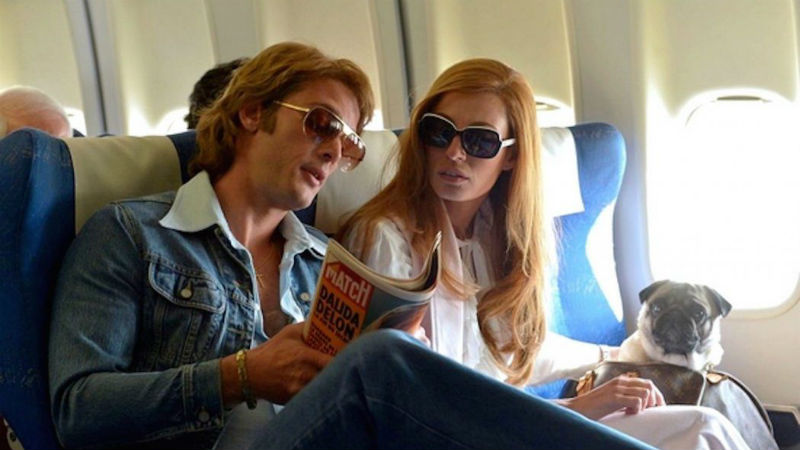

Love has rarely seemed more anodyne than in Vita and Virginia, which has a miscast Gemma Arterton and Elizabeth Debicki playing the two lovers. Here one of the most important women to have ever put pen to paper is reduced to a wholly passive, sickly, and sad woman, devoid of any true emotion, inspiration or true internalisation. Her lesbian lover, Vita Sackville-West fares no better, Gemma Arterton more focused on her aristocratic mannerisms than her transgressive personality or desire to shake the system. Together they seem like they’re still reading through the script.

Rent apart by circumstance and repression, the two women read their letters to each other looking straight to the camera Barry Jenkins-style (although without any of the same cinematic tenderness). Here one line-reading struck me as symptomatic of the film’s laziness as a whole. The text on the screen reads “We can live in the present moment – together”. There is a dash between the words “moment” and “together” yet Arterton rushes straight through the phrase, giving her plea no weight whatsoever.

Everything feels off. There is little at stake and even less to care about. In better hands, there might have been something vital to say about the role of women in society, the patriarchy, the coded nature of same-sex desire, the power of romantic inspiration and the relationship between life and art, but Vita and Virginia — based on the 1992 play by co-writer Eileen Atkins — is devoid of any nuance, allowing characters to simply say things out loud that another film would’ve played out through genuine conflict.

For the vast majority of people, passion and desire is a mixture of mental and sexual sensations. When you’re homosexual in a repressed society, this can result in a great conflict between the two — for example in the great Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017), which elegantly linked physical motifs with mental sensations to a highly sophisticated degree. Here, Vita and Virginia may spend a lot of time discussing the nature of desire — sometimes embarrassingly through a heterosexual mouthpiece who asks stupid questions like “How do women really have sex?” — yet is remarkably tame when it comes to the physical component; even recycling the same sex scene twice. It reflects the British biopic’s still reticent nature to portray homosexual relationships with any true spark or joy, resulting in a boring suffering-narrative that is potentially more damaging to homosexuals than truly helpful.

The overwrought score by Isobel Waller-Bridge, full of ahistorical synth nonsense, takes us out of the past and retrofits their romance to try and suit modern times. These aren’t helped by the cony sound effects, kisses bizarrely complemented by extremely kitsch ASMR breathing sounds. This Luhrmannisation is both annoying and alienating, elevating Vita and Virginia from the bland to the outright awful. Woolf deserves much better than this.

Vita and Virginia is in cinemas on Friday, July 5th. On VoD on Monday, November 4th. Stay at home and read a book instead.

DMovies selected Vita and Virginia as the turkey of the year of 2019…