At once a frantic city symphony in the style of Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis (Walter Ruttmann, 1927) or Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929), a social-realist drama about poor living conditions in La Paz, and a surrealist fantasy, The Great Movement is a fiendishly difficult movie to classify in regular terms. Playful yet obtuse, thematically dense yet light on its feet, its mixture of documentary and fiction refuses simple classification in favour of multiplicity and expansion.

It starts with a slow zoom into the city, allowing us to arrive into a dusty metropolis, filled with high-rises, endless exposed wires, the hum and thrum of traffic, bustling market stalls, and the constant sound of tripped car alarms. And it ends with the flow of rivers, showing all these people and their stories seemingly dissolving into the same stream.

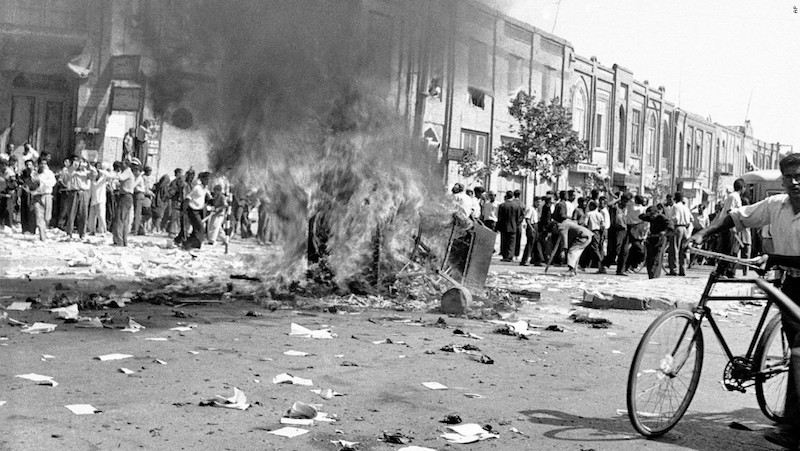

Within this circle of life enters Elder (Julio César Ticona), a miner with poor health who has walked for a week to protest against the government. But the journey has inevitably taken its toll on the middle-aged man, requiring him to look for alternative forms of medicine. This sets the film on its central contrast: rapidly sprawling urban development — signified by long-lines of burned out cars, chaotic construction work, and the criss-crossing of housing blocks — and its relationship to older, simpler ways of living.

Over two-fifths of Bolivia’s population is indigenous, the highest percentage in all of Latin America. The shaman Max (Max Bautista Uchasara), in a few patience-testing scenes, is seen living up in the woods, foraging for materials, unencumbered by the demands of modern life. But for the rest of the indigenous people in the city — like most people in the world — they have to make a compromise under capitalism, scuttling to and from work, engaging in back-breaking jobs while simply trying to get by.

Thankfully, director Kiro Russo, allows space for joy: whether it’s the banter of the women in the markets, random musical interludes that display a clear eye for movement and choreography or the desperate drinking rituals of the impoverished men. This is all given a retro sheen thanks to the choice of grainy super 16mm film, Italo-disco-sounding needle drops and an unhurried and confident tone, as if this is a film that has always existed, rather than something that was purposefully created.

If the film doesn’t completely cohere, it might be due to the fact that it doesn’t seem to want to cohere, instead shoring up a variety of symbols, throwing them in your eyeballs and seeing what sticks. This is best summed up by a psychedelic montage near the end, which appear to play the entire movie again in just a couple of minutes. Both semi-profound yet semi-ponderous, its a hard film to love, but an easy one to appreciate; not only for the scope of its ambition, but also its refusal to be easily understood. After all, the story of any city is a story of overlapping, competing ideas, jostling for prominence. Russo cleverly lets them sit side by side, favouring the power of overwhelming images to create a genuine sense of cinematic reverie.

The film opens in UK cinemas on April 15th. You can pre-order your seat at the Institut Français today! On various VoD platforms on Monday, May 30th.