his is an unusual title for a film about ballet. “A white crow” is a Russian expression for an outsider, someone who doesn’t quite fit in, an extraordinary person (some sort of antonym of our “black sheep). In fact, no description could be more apt for the subject of this film, Rudolf Nureyev, the greatest male ballet dances since Vaslav Nijinsky. It traces in outline Nureyev’s life from birth on a trans-Siberian train to his famous defection to the West at Paris’s Le Bourget Airport in 1961. The film is inspired by the book It is inspired by the book Rudolf Nureyev: The Life by Julie Kavanagh.

Nureyev could be a monster. The iconic ballet dancer was notorious for his selfishness, egoism, his temper tantrums, always demanding to get his own way even over the most trivial things. In a Russian restaurant in Paris, he doesn’t want pepper sauce on his steak, so he demands that his companion Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos) tells the waiter about his wishes. He won’t do it because the waiter is a Russian and thinks that Nureyev is a peasant. He demands that a director of the ballet company leaves the room because he thinks that the director and the man beside him are talking about him.

Nureyev was very insecure, worried about his origins in Siberia with its desperate poverty. He gets out of bed as a little boy to watch his mother leaving their dacha in heavy snow, dragging a small sledge after her in order to get essential supplies for the family. He feels abandoned by his stern father in a wood as he goes off hunting. He remembers his father’s hand on his back and compares it to the hands of the forgiving father in Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son, exhibited now in the Hermitage. He is a sinner, an outcast, someone who has not quite come up to standard.

All this probably drove his ferocious ambition, his determination to succeed, his absolute insistence that he would get his own way. This was probably augmented by his homosexuality. It has never been easy to be gay in Russia and it still isn’t. His affair with a German lover Teja Kremke (Louis Hoffmann) is briefly shown. He looks wistfully at men dancing together and flirting with each other in a Paris nightclub and knows that he must go West.

The defection scene in Le Bourget Airport is exciting and tense. He was supposed to have jumped over a barrier to get to the West. In the film he approaches two customs officers at a bar after being briefed by Clara Saint that he must formally ask them for asylum. Clara Saint has been rung up by her friend Pierre Lacotte (Raphaël Personnaz) and told to come to the airport immediately to exploit her connection with André Malraux (it impresses the customs officers) to get Nureyev in touch with those who can get him asylum. After desperate pleading by Soviet officials he walks through the right office door to freedom.

The film does not cover the years after his defection. Clara Saint gets no recognition from Nureyev for her help but then “please” and “thank you” were not part of Nureyev’s vocabulary. The meltingly beautiful Oleg Ivenko gives a very competent performance although his very good looks fail to convey Nureyev’s fierceness. Ralph Fiennes is a very submissive and gentle Pushkin (Nureyev demands that he be his dance tutor), having to put up with his wife Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova) seducing Nureyev. Alexey Morozov is the put-upon Soviet minder in Paris Strizhevsky, who can’t hold Nureyev back.

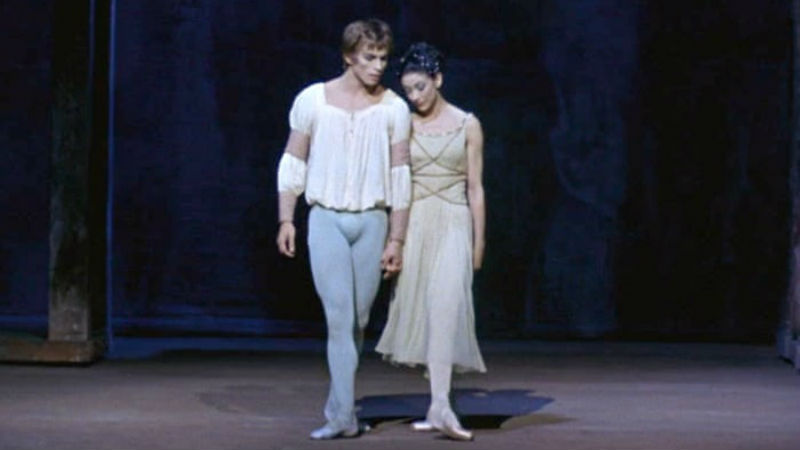

For all the difficulties of his personality, Nureyev brought much that was beautiful into the world. Those who first saw him dancing in Paris, said that his entries on stage were like “a bomb going off.” Ballet enthusiasts will love this film. It delivers lots of dancing eye-candy, both female and male. Nureyev himself was very beautiful and brought the best out in many beautiful people, including his dance partner Margot Fonteyn. The world is poorer for his passing.

The White Crow is in cinemas across the UK on Friday, March 22nd. On VoD on Monday, August 12th.