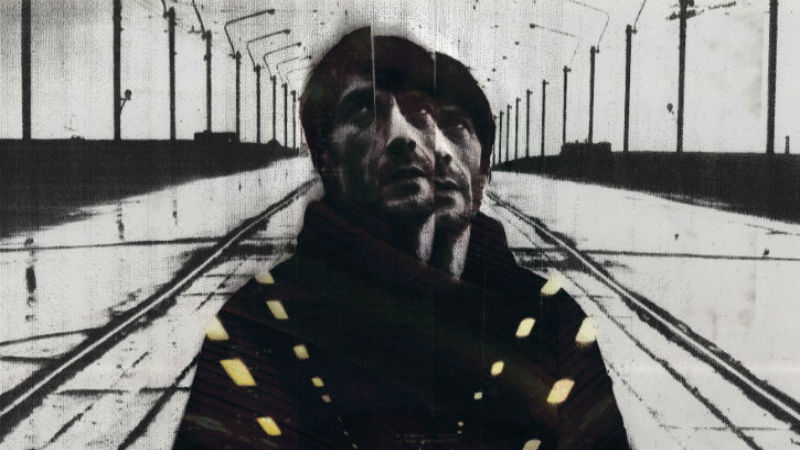

Felipe Hirsch is the kind of artist that I define as a “man who’s got an itchy issue”. By that I mean an artist that likes to venture into your discomfort zone. Is there any other explanation for a successful Brazilian playwright, who suddenly decides to film a movie in a foreign land? Moreover, working with actors whose mother tongue is neither his own nor English (the natural choice for those aiming for commercial success in the cinema industry)? Severina, which is entirely spoken in Spanish, is the outcome of this uncomfortable feeling.

The movie is a melancholic story of a certain Latin America. It is not by chance that its title resonates with a Brazilian cult play in verse, “Morte e Vida Severina” (The Death and Life of a Severino), by João Cabral de Melo Neto. The book is a Christian tale about an ordinary and suffering migrant in the Northeast of Brazil. The film, on the other hand, portrays an Uruguayan bookseller and aspiring writer whose small business is raided daily by a muse who steals his books. The muse (Carla Quevedo) is also an immigrant, from Argentina.

That certain Latin America that Severina shows is dying. The film is set in a decadent centre of Montevideo, where there are no 24 hours convenience stores. Its once glorious Art Deco buildings lacks life. Still, the main character (Javier Drolas) resists. He lives where he works but almost no one comes in in order to buy books. His solitude sometimes is broken by three or four friends. They come in to drink wine, talk about politics and read fragments of books. Does that happen anywhere else nowadays?

The feature is divided in chapters, or parts, in an order that challenges the spectator to define what is real and what is surreal. The second part is called “A loving delirium”, an obvious hint to a clever audience. The sound of the oboe and the Nouvelle Vague-ish cinematography sets the surrealistic tone. The characters, later, quote the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, probably the most significant figure in Spanish language literature since Cervantes. Borges also had his elusive and surrealistic muses.

Hirsh is not telling a story set in a distant and small country. Instead, the filmmaker describes what is happening just now in the digital world. Bookish geeks and literature lovers are a threatened species. Just walk down Regent Street or Oxford Street, the popular two commercial streets, in search of a bookstore. You will find only one amidst tons of fancy clothes, colourful shoes and mobile devices outlets. The world’s largest trade fair for books, Frankfurt Book Fair, is now reduced to an exchange of copyrights.

The beauty of the movie lies precisely in its moribund quality. Watching Severina is like taking care of a sick relative you love. You watch your old daddy falling asleep and you feel in peace because he is safe at home with you.

Severina is dedicated to the late Brazilian/Argentinian filmmaker Hector Babenco, and it premiered this week at Locarno Film Festival. You can watch it for free until August 20th, courtesy of Festival Scope.