Race and gender identity have become central topics in the world of cinema. The BFI has introduced diversity standards and even the Oscars are making visible efforts to become more inclusive of people of different colours and sexualities. The Best Picture Award for Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight is a testament of this, as is a related initiative to make membership more inclusive. These are all positive developments. So is it fair to say that anything goes in the fight for diversity?

Blackface became a no-go at least 20 years ago, and its racist origins are a perfectly reasonable justification. Such grotesque makeup was historically used in order to ridicule Black people, and to perpetuate the notion that they were primitive and less intelligent. It served well the myth of racial superiority upon which British Imperialism was founded, but it has no place in the 21st century. This practice should be confined to the museums and films archives only. The image above was taken from The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927), a film often remembered for being the first spoken picture in history but also conveniently forgotten for its racist connotations.

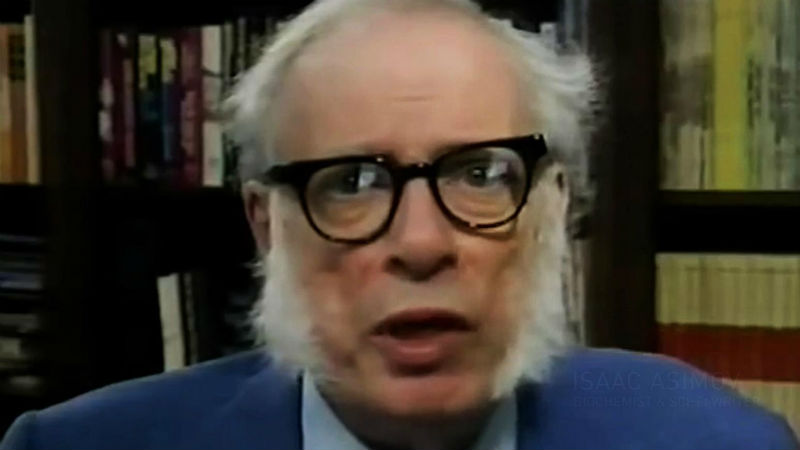

But what about yellowface? What about transface? What if the purpose is to celebrate certain minorities instead of mocking them? Is this acceptable? Scarlett Johansson was controversially cast to play a Japanese woman in Rupert Sander’s Ghost in a Shell (pictured above), which was out in the UK earlier this year. Meanwhile in France, cis actress Fanny Ardent was chosen to play the transsexual Lola Pater in the eponymous film by Nadir Moknèche (pictured below). Are these representations ok?

The answer is no. They too are offensive. Some representations are celebratory in intention yet degrading in nature. Just because one claims that they meant good this does not give them a mandate to represent anyone they wish. Firstly because the mockery could be subliminal. Secondly, even if they had the purest of intentions deep in their heart, their subconscious could be infested with clichés and misrepresentations, which only those affected are able to recognise. The outcome of yellowface and transface can be both toxic and patronising, just like blackface. Plus it prevents real trans and oriental actors from obtaining work.

So am I saying that we shouldn’t change anyone in front of the cameras, that makeup is entirely forbidden and that we should stick strictly to our everyday look when appearing in a film? Again, the answer is no. Cinema is entitled to celebrate transformation, metamorphosis, and this is in the very nature of the seventh art. The problem of course is: where do you draw the line between what’s acceptable and excusable in the name of art and what’s counterproductive in the battle towards inclusion and diversity?

In the name of art

There should be a poetic licence or a very subversive artistic statement for transface, blackface and yellowface, otherwise it’s not acceptable at all.

For example, Almodóvar has used cis actress Carmen Maura to play a transsexual and trans actress Bibi Andersen to play a cis woman. He has used such subversive devices in various of his films. He’s not mocking transsexuality but instead our shallow notions of identity. It’s as if he was saying: look, transgender/sexual people are fabulous; it’s us who deserve to be mocked for our inability to distinguish between gender and sexuality. And there are also films where people change their gender halfway through, such as Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992).

Well, the issue of race isn’t as black and white, forgive the pun. I cannot think of a film where the character changes his race halfway throughout*. And they haven’t made a film about Michael Jackson’s “whiteface” yet. Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959) could be perceived as some sort of “whiteface by proxy”, where the lead conceals her black roots in order to gain social acceptance in the US (pictured below). But this is not the same dirty and subversive device used by Almodóvar and Potter. There is no poetic licence. Sirk is instead making a very straightforward and even didactic anti-racist statement – and also a very effective one.

It is acceptable to use blackface and yellowface in cinema in order to discuss or mock the practices themselves, but not in an attempt to represent these minorities. I am yet to see a filmmaker that does that does that effectively, in the same way Almodóvar did it for gender representation.

So, what’s the limit?

We want race and gender representation to be taken seriously, and yet we don’t want to live in a PC-gone-mad world. So, how do we reconcile the two? Of course that’s not an easy task, and discussion will continue to flourish – thankfully so.

So do we stop young people from playing older characters? And do we prevent actors from delivering performances in a non-native language? I have a profound dislike of “languageface” and I also not very fond of people playing a character of e very different age. Again, unless the character changes in the movie (and, unlike race, our age DOES change) or there is a subversive twist/ poetic licence attached. But that’s just my personal taste, and at least I don’t think such representations are offensive. Instead, they are just silly.

In a nutshell, race and gender identity is where we should draw the line. It’s ok to represent people of a different age, language and culture, but it is NOT ok to represent people with a different race and gender identity. Bar the two caveats already discussed.

There is however one exception I am prepared to make. We should embrace every opportunity to do orangeface, therefore mocking and ridiculing Pussy-Grabber-in-Chief’s very natural colour. I hope a filmmaker will do that soon, and John Waters has already hinted that this might be possible, in his exclusive interview with DMovies. There is no shame in doing that. In the name of tolerance, we should claim the right NOT to tolerate intolerance, and Donald Trump is the epitome of intolerance. So let’s all get our orange paint out and encourage the most grotesque representation ever in the history of cinema!

* Since this piece was written our very avid readers have noted at least three films where characters undergo “racial transformation”: the Brazilian classic Macunaíma (Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, 1969), True Identity (Charles Lane, 1991) and Tropic Thunder (Ben Stiller, 2008). This is called race-bending. Plenty of dirty material for yet another article!