A remarkable hybrid of documentary and fiction tells the story of Laika, the first creature to be set into space by the Soviet Union. Growing up on the streets, the legend goes that she now roams Moscow as a ghost. Blending archival footage with remarkable on-the-ground tracking shots of wild street dogs, it is a bizarre, compelling and controversial tale, likely to provoke discussion for containing one of the most shocking documentary scenes seen all year. The brains behind the story are couple Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter, who also produced the film under their own company RAUMZEITFILM. We sat down with them to discuss morality, Soviet cinema, and working with four-legged protagonists.

Space Dogs has just premiered in the Concorso Cineasti del presente section of the 72nd Locarno Film Festival. You can read our film review here.

…

.

Redmond Bacon – What attracted you to the story of Laika?

Elsa Kremser – We wanted to make a film about a pack of dogs. But we had no idea where. Then we found out that Laika lived on the streets before she was sent to space. We had to go to Moscow.

RB – The narration is by famous Russian actor Aleksey Serebyakov. Why did you pick him as a narrator?

Levin Peter – We knew early on we wanted to have a Russian voice. Only a small part of the film has this narration, but it needed to be Russian because we wanted to create an atmosphere where you can imagine it’s an old scientist reading from his diaries, or a voice from the cosmos! Serebyakov was the first voice that we had in mind when we thought about a Russian voice.

RB – It reminded me of Aleksey Batalov in The Hedgehog in the Fog (Yuri Nortstein, 1975)…

Both Elsa and Levin – Yes!

RB – Discussing other Russian analogues, the subject matter also brought to mind classic Soviet film White Bim, Black Ear (Stanislav Rostotsky, 1977).

LP – Yes we love it.

EK – We watched it to better understand Russia’s relation to dogs. For them it’s a really important film. Every child in Russia has seen this film.

LP – When we watched it we were amazed by how they created a narrative about this dog. In comparison to American products, it’s much less humanising.

EK – And less pushy than something like Beethoven.

LP – If you compare these two movies, the Russian one wins.

RB – White Bim Black Ear is renowned for its unsentimental approach and very distressing scenes. Space Dogs has one scene in particular, which I won’t spoil as the film has only just premiered at Locarno, that is very violent! Did it just happen out of nowhere?

EK – Yes! We followed these dogs for weeks. Sometimes they slept the whole day and sometimes they were biting into cars. One morning this just happened. The entire team was immensely shocked!

RB – It’s interesting from a moral point of view: On the one hand it’s not something you want to see happen, but on the other, it does make for a great scene. As you’d expect, it provoked a few walkouts. How would you justify such a violent scene? How is it necessary in terms of the narrative?

LP – We really believe that there is no need to justify this scene. If you decide to make a film about dogs in the city who live on their own, it would be really stupid to believe that they will act like normal dogs. Of course we never expected this to happen. This was really a turning point in our production. We realised that night that we were working on something that was never shown before and in a way that was never shown before.

RB – It’s extremely well-filmed. How did you keep the camera stabilised for these low shots of the dogs? What equipment did you use?

EK – It took a long time to find the right equipment. Luckily the film is supported by Arri. They gave us all this equipment and helped us to develop this system. We shot with the Alexa Mini Body with a stabilisation system called Wave 2. The stabiliser is built by a little company in Munich [Betz-Tools], and it’s used for shooting on boats. But the beauty of the shots comes from cinematographer Yunus Roy Imer himself, because he had to put all his force into the movie; walking for hours and following dogs, all while keeping the camera steady.

LP – I want to point out the sound too. It’s a really fucked up job for a sound operator.

EK – To get footsteps of dogs!

LP – From the beginning we thought this is going to be a sound movie. From the beginning on we really wanted to hear the tiniest movements and the kind of sounds dogs make.

EK – It was very hard because we could not ask [our team] about any previous experiences. We had to invent everything. How can you arrange a sound recording system for this kind of specific thing? How can you arrange a camera system?

RB – Did you pick all the sounds up on mic, or is there also added foley work?

EK – In Moscow we also made foley recordings with the dogs because every dog has very different footsteps. It was a big collection.

LP – The archive footage was silent. We had to start from scratch.

RB – How did you find the archive footage? Was it all based in Moscow?

LP – It’s all from Moscow. We had brilliant support from Sergei Kackhin. He helped us stay brave enough to wait years for access. One source is the Russian State Archive for Scientific-Technical Documentation. It’s a huge archive where everything that was once invented in the country is stored. Much more interesting is the institute where the dogs are trained. In the basement there were mysterious reels of 35mm footage. Yet from the moment we were told about it to the time we digitised it, three years passed.

RB – How difficult was it to navigate Russian bureaucracy? Was it difficult administratively or was there also political pushback?

LP – It’s a very personal pushback. Of course it’s a huge system. There’s a lot of bureaucracy. But first you have to gain the trust of the person who is directly responsible. It’s interesting because when you enter nothing is possible, which we have also experienced in German archives, where the bureaucratic level stays the same. But in Russia, as soon as they understood our mission and what we wanted to do, they were more open.

EK – But we did struggle with the ongoing tensions between Russia and Europe, especially in the media. There have been scandals that have thrown us back for months. Every time something came up on a big German TV channel, they would say: “OK, no. Now it’s done you cannot come anymore and we don’t give you the material.” Then several months later, we talked again and again, and we made more progress.

RB – Most Western depictions of Russia don’t do much to help these tensions. What I found refreshing about Space Dogs is you don’t otherise Russia at all. There’s a conscious effort to see their treatment of dogs as a universal problem rather than through a stereotypical Anti-Soviet context.

EK – Yes. With the monkey scene [the American government sent the first monkeys into space] you can see that it happened all over. We also thought that these dogs are not Soviet or Russian. They might be inhabitants of these countries at these moments in time but these animals don’t have nations. We never wanted to be too pointed with the Russian angle. We wanted to show it’s a global thing.

RB – The Soviet Space Program has brought untold benefits for mankind, and is a huge achievement, yet for me, watching the way these dogs have been treated, I wondered: was it really worth it? What do you think?

LP – It’s such a difficult question. We still don’t know what will happen in the next 50 years. It would be naive to believe that everything they developed with dogs — such as the rescue systems and bringing living beings back to earth — wouldn’t be possible without these tests. It’s the same moral question when animal testing comes up; in cosmetics or medicine…

EK – But of course there’s the point that with medicine people survive thanks to them. The dog experiments raise the question: why do we want to conquer space so much?

RB – The film also challenges people’s perceptions about dogs. If the film was about rats in space, no one would care.

EK – And there are plenty of rats in space!

RB – Dogs are considered to be man’s best friend. But this film challenges this idea and asks: are dogs naturally domestic or are they actually quite wild and feral? Are you trying to change the way people understand dogs in society?

EK – Of course. We think it’s weird that we always want to be their boss. With the film we turn it around a bit and say it’s not just us controlling them. They have their own world.

LP – The Space Program was also about entertainment. It’s the same in our film, in a way. They are the main heroes. We followed these dogs and of course we gave them names and projected some kind of human behaviour onto them. It will happen with everyone who has seen this film. There is no escape.

RB – Thanks to the low point of view and lengthy shots of the dogs, its a very immersive experience. Are you trying to get people to imagine what it might be like to be one of these animals?

LP – Of course. To raise the question of how I, as a human, might look like from this perspective. From very early on we know that dogs are part of our world, but we know nothing about ourselves as part of their world. We know nothing about the role we play.

EK – What we enjoyed personally from watching our own film is that sometimes you can forget these are dogs. You can feel just like you’re in a movie and the main character is falling in love…

RB – Moving onto the Moscow setting. The dogs are filmed a lot at dusk, dawn and nighttime. The sky is electric orange and there’s not many people about. Was it your intention to make the city this kind of otherworldly place?

LP – It mostly came out of the situation, because these dogs mostly sleep during the day. At night, when the humans go home, this is their space. During early research there was a moment where we knew we could make this movie. We went to a factory where a pack of dogs were living. We came during the day and they were just sleeping. I thought: “It’s interesting but how can we do a movie with just sleeping dogs?” Then Elsa said: “Let’s try again at six am.” When we went the whole street was full of dogs. One pack was fighting against another…

EK – [interrupting] They were mating! Then we knew we had a movie.

LP – The good thing about the movie is that the more interesting people come out at night too. They really have a connection to the dogs, like the homeless man searching for goods in containers. It’s very obvious that he has his own language with these dogs.

RB – Circling back to the very beginning of the movie. It starts in space, then there’s a very trippy scene depicting Laika re-entering the earth’s atmosphere. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) homage?

EK: Of course. Especially in the sound design, we had a lot of inspiration.

RB – The music too; it sounds very cool.

LP– When we were finishing the music with composer John Gürther, we watched this 20 minutes of tripping in Space Odyssey again; just to check once again how it works on the audio layer.

EK – For music and sound development we watched hundreds of space films. Especially 70s.

LP – We liked The Andromeda Strain (Robert Wise, 1971). This was really the direction we wanted to go in.

RB – You’re currently working on a fiction feature set in Minsk, Belarus [The Green Parrot, telling the story of a 34 year-old autopsy assistant who falls in love with a 17-year-old woman, is currently in development]. What draws you to the Russian speaking world?

EK – The reason our next film is set in Minsk is a bit of a coincidence. It was not an intellectual choice, like: “We want to go to Minsk to tell a story about a guy in a morgue falling in love.” Coincidentally we fell in love with this area of the world.

LP – We grandfather taught Russian his whole life. There were Russian friends visiting my family once a year. We started to explore this world together from the first moment on. But it was never a choice to say: “We dedicate our lives to this.”

EK – It somehow happened.

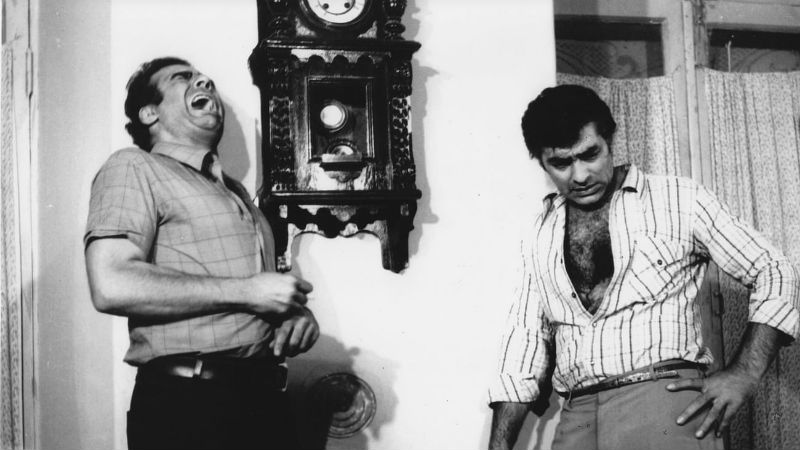

Picture at the top: Locarno Film Festival, Marco Abram. The other images are from the film