Twenty years ago, Kazem made a film about the village’s women being unable to bear children. As a result, they beat him up. And many of the men in the village divorced them only to feel guilty and remarry them some three times. Now he wants to make another film because the problem may lie not with the women, but the men. Who, reckons the narrator, are equally likely to beat him up. A visiting lady doctor, generally referred to by the locals as Miss Doctor, hopes to run tests on the villagers and establish the cause of childlessness.

Moslem, who is also the narrator, wants to learn how to be a director – and to just be in the film. He claims that all the women in the village are related to him, so he’ll have no problem getting them to talk on camera. But, of course, it doesn’t work out that way.

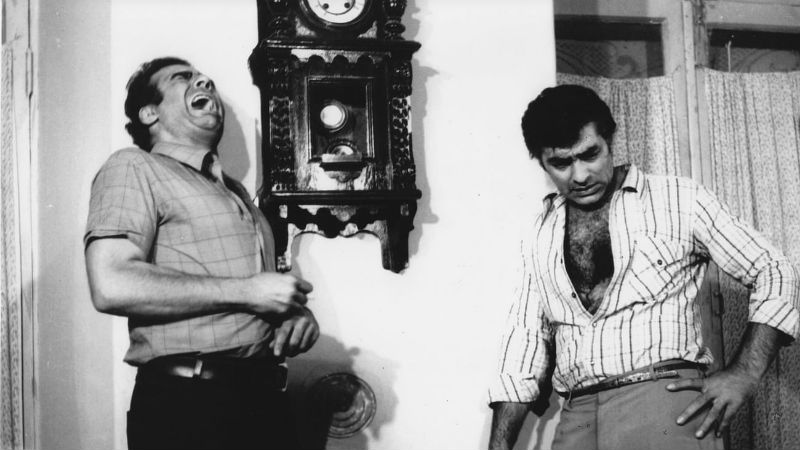

An hilarious running gag has people going up to local sound recordist Samad and asking him this or that while he’s trying to record sound. Director Jamali has a lot of fun with elements such as this – for instance, Moslem proudly proclaiming that he’ll use the clapper board so professionally that no-one will need to do any writing. Or tossing leaves onto a patch of ground in an unsolicited attempt to make the shot look more beautiful for the camera.

“When you show up,” one of the women tells Moslem, “there’s always someone dead or something wrong.”

Another episode has one of the oldest women in the village – Granny Nazi – about to give birth. Kazem wants to film her, but her menfolk are unwilling. Eventually a compromise of sorts is reached and Samad, having agreed to record sound after the birth, promptly installs himself on the roof to record the event itself.

The film abounds with gags about the art of filmmaking. Kazem screens a silent film for the men of the village, but they want to know why it has no sound. Elsewhere, one man wants to be recorded in sound only so his relative won’t know from whom the testimony comes. So Moslem borrows a frosted window pane from a local house to use to blur the on camera image while the man is being filmed. Only, he can’t resist moving the glass so that the camera glimpses the man’s face.

Like Italian documentary The Truffle Hunters (Michael Dweck, Gregory Kershaw, 2020), in which the old men of the village prove so incredibly watchable on camera, both Moslem and, to a lesser extent, Kazem, bring an irrepressible humour to the film. Unlike that film, this one isn’t a real documentary so much as a film about three characters making one. Its heart is in absolutely the right place, though, with its story about a group of women who got a raw deal as a result of patriarchal prejudice that blamed them for infertility that turns out not to be their fault but the men’s.

Audiences will be drawn to it not because of what it has to say about male bias and injustice but rather because of the humour with which it achieves this. A quiet, gentle and genuinely funny little film.

A Childless Village premiered in the 26th Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, when this piece was originally written. It then shows at the 2nd Red Sea International Film Festival.