Iranian cinema can be as well defined by what it doesn’t show as by what it does. Women’s hair is never seen, characters never drink and sex is never depicted. Filmmakers, like Jafar Panahi (still technically under house arrest), must find novel ways to skirt restrictions to say what they want about life and society. What’s truly incredible is that despite these restrictions, Iran can lay claim to one of the richest cinematic cultures in the world.

Style follows form, the government’s rigid censorship paradoxically leading to some remarkably powerful works. Could the metafictional stylings of Abbas Kiarostami or the tightly wound social dramas of Asghar Farhadi have come out of a more liberated society? Perhaps I have been thinking about it all wrong. As the documentary Filmfarsi shows — surveying popular Iranian cinema up until the Islamic revolution of 1979 — Iranian cinema has always been characterised by wild invention, improvising with what you have and melding genres together.

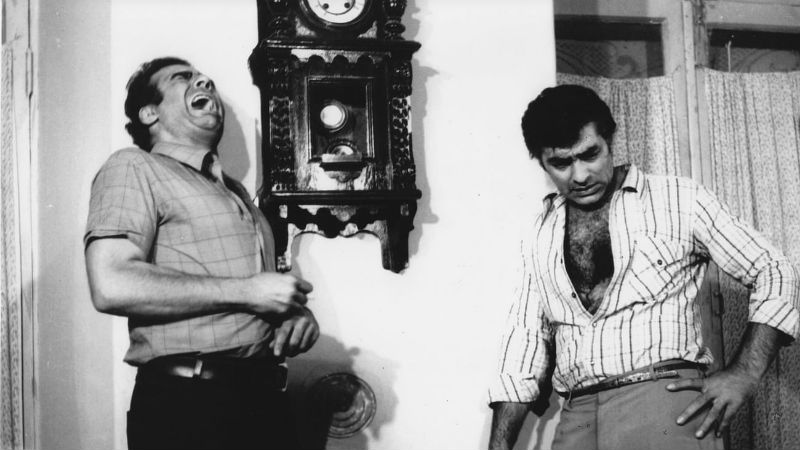

Documentarian Ehsan Khoshbakht, narrating with the air of a seasoned university professor, calmly takes us into the world of Filmfarsi, cheap and dirty pre-revolutionary cinema revealing a completely different side of Iran. These are brazen, erratic works, seemingly shot on the fly and infused with sex, alcoholism, and violence. Plot-lines are often ripped off from Hollywood works, interspersed with dance scenes that act like a cross between Egyptian dance and Bollywood musicals.

Yet none of these Filmfarsi works, converted from rare VHS rips, are allowed to be screened in Iran; considered to be totally antithetical to the Islamic way of life. After the revolution, cinema halls were burned down and actors and filmmakers were forced into exile (although paradoxically some, like Kiarostami, went on to become household names in Iran). This gives Filmfarsi a great feeling of poignancy, both for a lost way of Iranian life, and the cinematic styles that went with it.

While it’s easy to think of cinema, a relatively recent invention, as an art-form that can easily be preserved, the reality is far more porous. Disintegrating film footage, producer meddling, endless rights battles and overall lack of care has led to many great masterpieces being either partially or completely lost. How much great Iranian cinema is still out there, yet to be (re)discovered or never to be found again?

When it comes to understanding the soul of nations, film becomes a highly useful tool; capturing a people’s attitudes, paradoxes and ways of life. Therefore, whether it’s the irreverent comedies from the Soviet Union, or Pre-Code Cinema of the USA, preservation of the past becomes both a means to fight against prejudice and to peek into alternative futures. By ripping up everything you thought you knew about both Iran — one of the most misunderstood nations on earth — and the Iranian cinematic tradition, Filmfarsi is yet another reminder to look beyond stereotypes to the far messier truth underneath. Khoshbakht’s approach is mostly academic, offering only a couple of personal anecdotes about his relation to the material. While a few more personal anecdotes may have imbued the film with even more melancholy, his love for the contradictions of the genre runs strongly throughout. Essential for lovers of Iranian cinema.

FilmFarsi premieres at the Cambridge Film Festival, which takes place between October 17th and 24th.