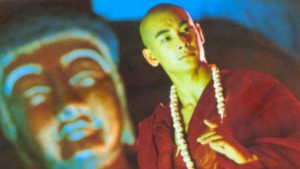

QUICK SNAP: LIVE FROM THE TAALLINN BLACK NIGHTS FILM FESTIVAL

This is a spectacularly dirty movie. It’s unlike anything else you have seen before. The creative sentience is entirely palpable. There’s plenty of clucking, cackling, plucking and ruffling feathers. And it isn’t just chickens that suffer. Human beings are subjected to the very same type of abuse as our edible friends.

The plot is deceptively simple. Tao works at as a chicken slaughterer in the heart of a bustling city, presumably either Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh. His relationship to the birds is ambiguous and dysfunctional. They are his closest companions, but he’s also prepared to butcher them in the most horrific ways at any given minute. One day, he peeks on three gangsters dwelling in an abandoned building with a prostitute. He gets discovered, and the three criminals turn him into some sort of jester and slave. He’s forced to emulate chickens in order to entertain them, He also has to feed them. But Tao has a cunning plan, and soon tables could be turned. The hunter could get captured by the game.

Drowsy City is guaranteed to ruffle feathers amongst animals lovers. The butchering of chickens is extremely graphic. They are boiled alive, defeathered and beheaded in front of our very eyes. When talking about Weekend (1967), French provocateur Jean-Luc Godard said that he opted to show a real pig being killed simply simply because it was acceptable to show animals being murdered in cinema (unlike human beings). Dung Luong Dinh is clearly aware of this contradiction, and uses this controversial device to his advantage.

But it isn’t just animals who suffer. The Vietnamese director mercilessly exposes the frailties and vulnerabilities of us human beings. Chickens are merely a proxy. We too get burned by boiling water. We too can get killed by a slaughtering knife. We don’t even have feathers to protect us. Our skin is directly exposed. In the titular drowsy city, both chickens and human being are caged, trapped and tethered. These creatures understand the inevitability of death. Our relationship to each other isn’t more humane than our bond to birds. We are prepared to humiliate, torture and kill each other.

Water is a recurring theme. It is is fluid and ambiguous. It washes away the blood and the feathers on the ground, but it also serves to boil and to drown. Tao takes pleasure in a sitting in a tiny tub filled with water, or to lie down outside allowing a tropical storm to pour over him and soak his clothes. It’s a purification ritual. He’s preparing himself for something much bigger.

Aesthetically, this is fascinating endeavour. Camera angles are slanted, buildings derelict, cracked walls dirty with mould and faded paint, the floor covered with blood. Extremely high drone shots remind us of our anonymity and urban solitude. The city is teeming with action, and yet we are blithely oblivious to what our neighbours are up to. Our indifference towards our fellow human beings isn’t dissimilar to our bond to the chicken on our dinner plate. Everyone is prey.

Drowsy City just saw its world premiere at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. It’s showing in Competition.