Made and released in the brief period of about a year between the collapse of one dictatorship and the rise of another – and the temporary relaxation of state censorship that accompanied it in South Korea – Aimless Bullet deals with the struggle to survive in that country amidst economic collapse. Men including demobbed soldiers and officers try their hardest to find work, others lucky enough to have jobs struggle to support their extended networks of loved ones while women drift into prostitution – or, if they’re really lucky, become movie stars.

It opens with crippled, former military officer Gyeong-sik, constantly asking Sgt. Park and other drinking buddies not to call him ‘The Commander’, making a scene in a bar and smashing a glass door. Wandering through the streets at night alone afterwards, he’s accosted by former girlfriend Myeong-suk (Seo Ae-ja) who desperately wants him to fulfil his promise and marry her, but he won’t because as a cripple he feel an incomplete man.

Myeong-suk meanwhile is prostituting herself to get by. One of her brothers Song Yeong-ho (Choi Mu-ryong) is determined to find work and looks to have struck lucky when ascendant movie actress Miss Goh gets him a starring part in a film. But when he learns that it’s about a soldier with wounds just like his, he turns the part down. He can’t afford to by his niece Hye-ok the new pair of shoes he’s repeatedly promised her and the little girl has become accustomed to think of him as a liar. Things seem to be looking up when he meets Oh Seol-hui, formerly a woman lieutenant in the army, but their blossoming romance is cut short by tragic circumstances beyond their control their control. Frustrated, he decides to rob a bank – but then that goes wrong too.

His brother Song Cheol-ho (Kim Jin-kyu) suffers from toothache but is loathe to spend the money to get it fixed. As well as his daughter Hye-ok he has a son who bunks off school to make money selling newspapers. His wife (Moon Jeong-suk, star of A Woman Judge) is pregnant. He’s ground down by the daily drudge of working at Kim Seong-guk’s Accounting Office.

As the Commander and the woman lieutenant drop out of the plot to enable the narrative to focus on the two brothers, it lurches towards something like A Day Off, part crime thriller and part noir angst in a world where any promise of a better life always has another, less pleasant side to it.

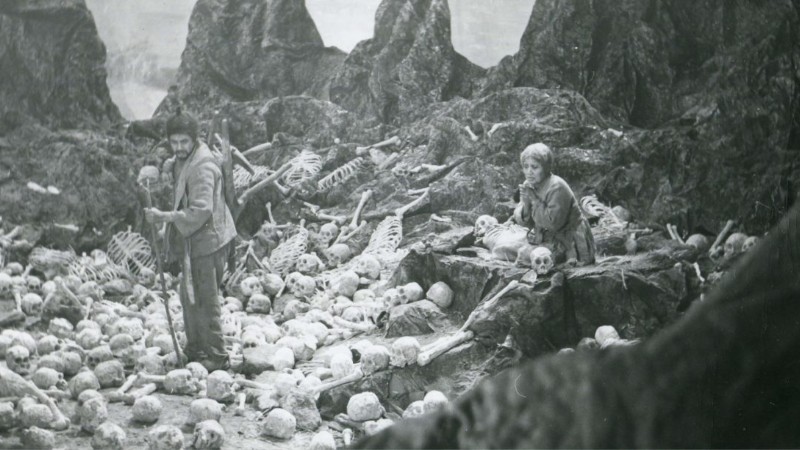

Perhaps this is best represented by the scene where, like those of the confused heroine of Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock, 1929) Cheol-ho’s feet walk the streets. His eyes pass shopfronts filled with consumer products he can’t afford before he succumbs to visiting a dentist and paying for a tooth extraction. Even then, he’s told he can only have one wisdom tooth removed per visit, so even that proves less than satisfactory. He slumps into a taxi but keeps changing his mind as to where he wants to go. He has become, as he describes himself, an aimless bullet. The film, by way of contrast, knows exactly what it’s aiming at and in its final scenes hits its target – that of showing the human cost of economic depression – head on.

The film is also known as The Stray Bullet, although given the script’s content Aimless Bullet seems a more apposite translation.

Aimless Bullet plays in LKFF, The London Korean Film Festival.

Wednesday, November 13th, 18.30, Picturehouse Central, London – book here.

Monday, November 18th, 20.20, FilmHouse, Edinburgh – book here.

Tuesday, November 19th, 18.20, Queen’s Film Theatre, Belfast – book here.

Saturday, November 23rd, 13.15, Home, Manchester – book here.

Watch the Festival trailer below: