Turn on the fan on and grab yourself an ice-cold drink. As they always say: “if you can’t handle the heat, get out of the cinema!” Oh, isn’t that what they say? Well, nevermind, my brains are frying and I can’t think straight.

Regardless of how the saying goes, we have picked 10 films set during very hot weather (mostly heatwaves) across all parts of the world for you to enjoy with a big jar of Pimm’s. Or perhaps just wait until the weather has cooled down so you can reminisce about the scorching good moments while looking at these people loving, fighting and also being tortured under the heat!

There are rabid rodents on fire in Brazil, Austrians running amok, separatist Brits dying with thirst, black New Yorkers sizzling on the pavement and even a sadist German torturing his spouse who’s suffering from insolation. These are the top 10 heatwave movies, exclusive for the June 2017 UK heatwave!

…

1. Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

How do you add a touch of tension to one of the biggest murder movies of all times, which spawned an entirely new voyeur/binoculars subgenre? What about turning the temperature up by a notch or two? Jeff (James Stewart) is very nervous at having juggle a likely murder across the street with his stormy relationship to Lisa (Grace Kelly). Hitchcock suddenly cuts to a close-up shot of a thermometer revealing a very hot temperature, which is backed up by the sweat on the face of Stewart’s character.

2. Passport to Pimlico (Henry Cornelius, 1949)

This Ealing comedy is probably one of funniest films you will see in your life. The residents of Pimlico find an ancient parchment revealing that their London district has been ceded to the Duchy of Burgundy in the 15th century. As a consequence, they become a sovereign state. Independence occurs in the middle of an unseasonably hot summer, and the former subjects of the King immediately indulge in late night drinking and eating – as they ditch rationing and pub closing hours. The problem is that the British soon begin to boycott them, and they have to rely on international cooperation so they don’t die of thirst or starvation.

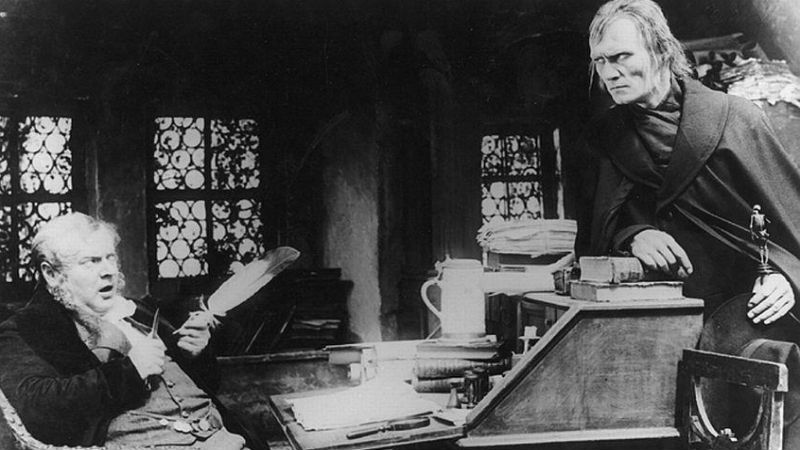

3. Dog Days (Ulrich Seidl, 2001)

Historically, the title of this extremely disturbing Austrian film refers to the period of Greek and Roman astrology connected with heat, drought, lethargy, fever, mad dogs and bad luck. In Europe, these days are now taken to be the hottest, most uncomfortable part of summer. Ulrich Seidl, one of DMovies’ favourite directors alive, translated this into euphoria strangely blended with insanity. Vienna is the backdrop to six anecdotal tales of twisted sexuality, scorching obsession and bizarre compulsion. The picture illustrating this article at the top is also a still from Dog Days.

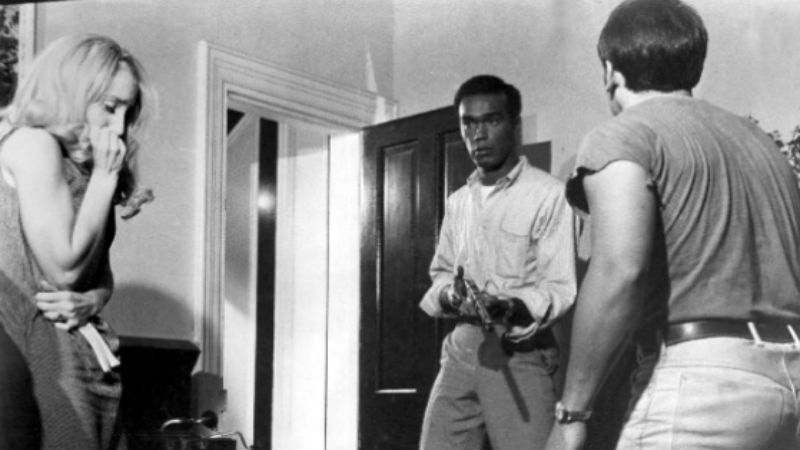

4. Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

Both temperature and racial tensions quickly rise in what’s widely considered Spike Lee’s most iconic and emblematic movie. Salvadore (Danny Aiello) is the Italian owner of a very traditional pizza restaurant in Brooklyn. One day he is confronted by the local Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito) because his Wall of Fame does not include any black actors. The sweltering sun is the perfect catalyst for this incendiary racial argument, which incenses the entire neighbourhood.

5. Rio 40C (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1955)

This highly neglected dirty gem of Brazilian cinema is a semi-documentary of the people of Rio de Janeiro, particularly the poor boys selling peanuts on the sultry beaches of the city. The movie doesn’t have a protagonist, but instead a number of subplots that are sometimes intertwined. The oppressive heat is the common theme across the movie: it both connects and sustains the characters. Significantly, Brazil’s former president Lula used to sell peanuts as a child.

6. Rat Fever (Cláudio Assis, 2011)

It’s not just Europeans that go mad under the heat of the sun. Similarly to the expression “dog days”, “rat fever” here denotes a delirious state of mind exuding hedonism. This also Brazilian movie depicts the lifestyle of an artistic community living in tropical city of Recife. The small group lives without laws, without rules and yet there’s no shortage of hot sex, poetry and inebriation.

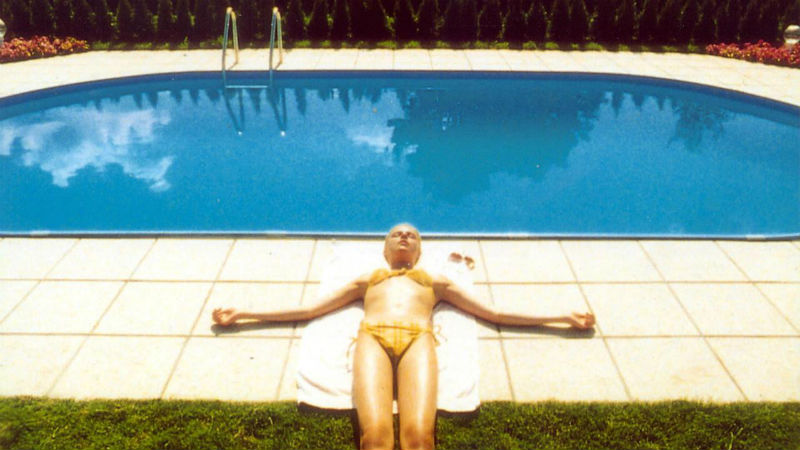

7. Martha (RW Fassbinder, 1974)

During holidays in Italy, Martha (Margit Carstensen) falls asleep on the beach while sunbathing, despite asking her husband Helmut (Karlheiz Böhm, who British eyes might recognise from Michael Powell’s 1960’s classic Peeping Tom) to prevent her from doing so. In reality, Helmut is a sadist, and he forces himself upon Martha while he’s fully clothed with a suit (pictured below) and she is in profound agony from likely insolation or sun stroke. Will make you want to avoid the beach for the rest of your days.

8. Coup de Chaud (Raphaël Jacoulot, 2015)

Life ain’t easy in a small village in the south of France struck by a heatwave, and where water becomes increasingly scarce. Residents and farmers begin to quarrel over the precious liquid, and their conviviality quickly flies out of the window. Nothing can calm them down, and even a mentally disabled man is soon victim of the hostility. Is water indeed the only way of cooling these people down?

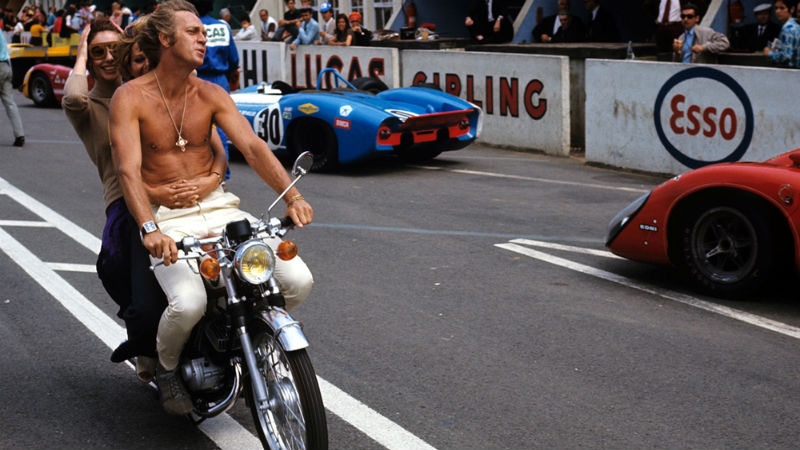

9. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962)

This historical epic was nominated for 10 Oscars in 1963, and it snatched seven in total. It’s often considered the greatest British movie of all times, if not a very dirty one. It depicts Lawrence’s predicament in the Arabian peninsula during WWI, dealing with inflammatory and fiery themes such British imperialism, national identity and split allegiances at war. The scorching sun is central to the movie, particularly as Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) crosses the Nefud Desert in search of water.

10. My Summer of Love (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2004)

Enough doom and gloom. We have decided to wrap up our list with a bright and glistening Lesbian love story set in the idyllic Yorkshire countryside, and directed by Polish-British filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski. Working-class Mona (Natalie Press) meets the wealthy Tamsin, who’s far more used to a mollycoddled lifestyle. Their romance is soon ignited, in a feelgood and yet realistic enough picture which will not fade away from your mind, unlike your summer bronze glow.