ArteKino is back this month only. Until December 31st, you can watch 10 dirty gems* of European cinema entirely for free and without budging from the comfort of your sofa, chair, desk or bed! the selection includes five films made by women directors. Film-lovers from 45 European countries will be able to explore a rich selection of films by established directors and also nascent filmmakers, along with outstanding performances by a new generation of on-screen talent.

We took the opportunity to have a word with Olivier Pere, the Artistic Director of the ArteKino Festival. He has revealed the dirty secrets of a such an exciting initiative. ArteKino’s selection is genuinely audacious and distinctive. This year’s selection includes films from countries as diverse as Austria, Greece, Poland and the Netherlands. Dirty topics include a critique of savage capitalism, growing up in a prostitution environment, abortion under extreme circumstances and much more. You can check out the full list and our exclusive reviews by clicking here.

*Only eight films are available to view in the UK, and there are restrictions in other countries, too.

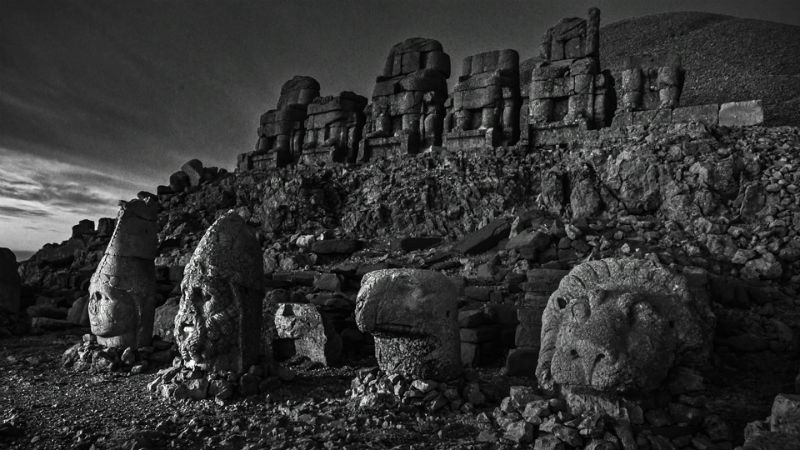

Image at the top by Bertrand Noel. Images below from Flemish Heaven and L’Animale, respectively.

…

.

DMovies – When and how did Artekino begin? Where did the idea come from? What are the aims and objectives of the initiative?

Olivier Pere – The idea behind the ArteKino Festival was born three years ago, when ARTE was looking to increase its support for European cinema in an innovative way. We came up with a completely digital festival that would be free for internet users all across Europe. Over the course of three editions, we have refined the way in which the festival operates, but the initial principle and goals remain the same: promoting the distribution and recognition of independent European cinema by selecting 10 remarkable arthouse films from major international festivals that have not found their way into theatres outside of their home country.

DM – Tell us about the curatorship. How do you view and select the films each year?

OP – I am in charge of the artistic direction of the festival. I identify films at festivals and in international sales agents’ catalogues. I see some of the films at festivals, and most of the time sales agents send me links to films that I ask for in order to make my selection.

DM – You describe your selection as “10 bold films”. What’s your definition of “bold” and of “art cinema”, and what are the selection criteria for your films?

OP – I choose films according to their quality, their originality, and of course their availability. We try to offer a balanced selection that can include films of various genres, from fiction to documentary, while remaining very attentive to the diversity of European languages and cultures represented (generally one film per country) and to the gender balance of the directors. Artistic boldness can come from a film’s aesthetics or from its subject matter, and how those things relate to contemporary themes.

DM – According to an industry player, only 37% of European films are seen outside their home market. Does this reflect your experience? And what should we do in order to improve this figure?

OP – Yes, and that is why we have developed the ArteKino Festival. We look for films that have low visibility outside of their country of origin and the festival circuit. Some of these films enjoy success in their home country but have difficulty travelling beyond national borders. This is true of comedies, but also of other films. Our festival is a way of crossing borders while staying in the comfort of one’s home.

DM – What’s your message for aspiring filmmakers everywhere who’d like to see their film on ArteKino?

OP – Young directors often need international festivals to receive critical acclaim and to enable their films to travel, as well as to be sold. With the ArteKino Festival, we offer them a way of reaching new audiences by inviting viewers who don’t have easy access to new European arthouse films.

DM – What’s your message to film lovers everywhere overwhelmed by the vast choice of VoD everywhere? Why should they watch films on ArteKino?

OP – We should specify that we are campaigning for movie lovers to continue discovering films in their original birthplace – the movie theatre. ArteKino Festival acts as a complement, not a substitution. Unfortunately, due to their location, some people do not have access to movie theatres that screen arthouse cinema. And it is no longer possible to assume that all films can be distributed in theatres – there are simply too many films being made, and there is a lack of diversity in a number of countries. That is why we invite them to discover new films free of charge in this new festival format.