QUICK SNAP: LIVE FROM THE TALLINN BLACK NIGHTS FILM FESTIVAL

In his third feature film, Turkish director Can Evrenol moved away from adult horror into partially new territory: children’s horror/fantasy. Peri (Denizhan Akbaba) lives with her father in a house in the woods. She has no mouth, literally. She drinks liquid through her nose and injects solids through a tube attached to her stomach. One day, her uncle Kemal shows uninvited and kills her father and dog. Peri runs into the woods and joins a group of three boys around her age, who call themselves “the Pirates”.

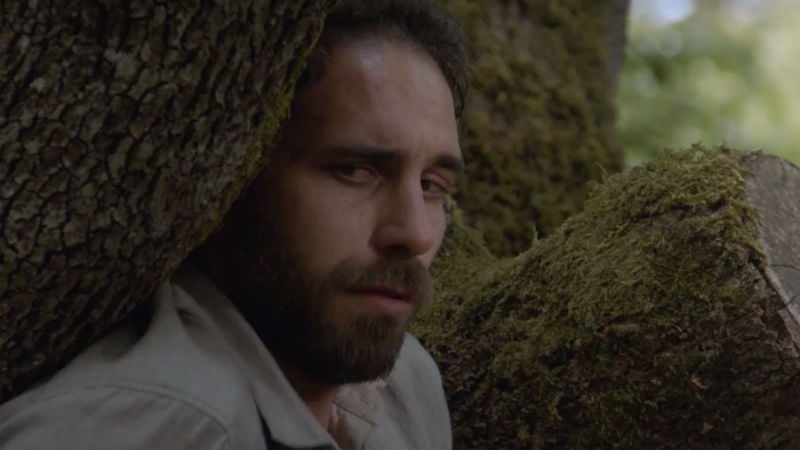

Kemal works for “the Corporation”, an elusive organisation that’s somehow responsible for the apocalypse that has befallen the region. We never learn the details of what happened, yet we do know that Kemal is intent on killing his niece and the other three boys. The four children were born with deformities. One of boys has no eyes, the other has no ears and third one has no nose. They rely on each other for the senses that they do not possess. For example, the no-eyed boy depends on others for vision. Peri relies on her friends for speech. And so on. The foursome must stick together in order to survive.

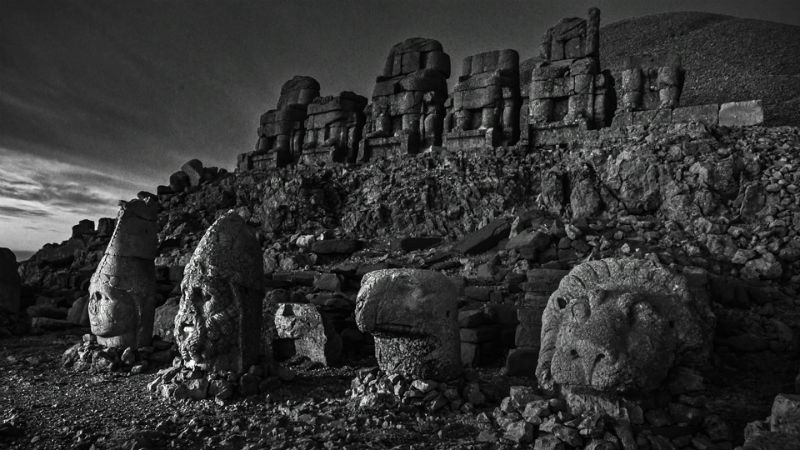

They come across abandoned buildings and vehicles, in what looks like a civilisation nearing its extinction. They must keep on moving in order to evade Kemal and his thugs, and also in search of food. They enter a large mansion and come across a rifle-toting formidable old lady. Maybe she isn’t as menacing as she seems. Could she become some sort of motherly figure and join them on their crusade against their evil hunters?

Not all is doom and gloom. There are touching elements of solidarity and an important message of tolerance, reminding children that they must support each other despite their differences. These differences are not a handicap. In fact, they complement each other. And no disability makes you a human being of lesser value.

The Girl with no mouth is indeed constructed as a children’s movie. The Manichæan battle of good versus bad, with a very simplified plot. The didactic message of tolerance and diversity. A child’s adventure: pirate clothes, slingshots and swords. And as such it’s more likely to rivet and enthral little human beings. Those under 12 years of age will likely holler as our four juvenile heroes contend with the malevolent adults attempting to kill them. Grown-ups less so, even if the movie is still enjoyable enough to watch.

Girl with no Mouth has just premiered in Competition at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. A very unusual selection, normally reserved for specialist festivals and festival strands.