The year of 2017 in British independent cinema saw a shift in perspectives on contemporary life distant from street lights and 24-hour takeaways. Their depictions of country life, God’s Own Country (Francis Lee) and The Levelling (Hope Dickson Leach; pictured above) simply do not just use their stunning vistas as a reflection of a character’s isolation, they interact with a filmic representation of rural life and class that has been prevalent in European cinema for years, specifically in the films of French duo Dardenne brothers and more recently, illustrated poignantly by JR and Agnès Varda’ in Faces Places (also from this year).

Forget Leigh and Loach; this was the year of Lee and Leach. Away from the defining voices of arthouse British film as Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, who have not released any films in 2017, first time feature length directors Hope Dickson Leach and Francis Lee construct tactile debuts that speak to a repressed and reserved sense of Britishness that currently results in suicide being the leading cause of deaths in men aged 20-49. Similarly, their underlying socio-political connotations, their films speak to contemporary Britain in Eastern European migration impact on the Brexit vote and a wide demographic of untraceable Conservative voters who helped keep the Tory’s in power during the 2015 and 2017 General Elections. Their emotionally unstable and insecure male characters speak to a present day society engulfed with a fake sense of nationality. By looking to European filmic influences, Leach and Lee speak to a class and themes deserving of their time in the cinematic spotlight.

.

Long and winding country road

After gaining the ‘Star of Tomorrow’ Award by Screen International ten years ago for The Dawn Chorus, Hope Dickson Leach’s arduous task of getting a full feature film made speaks to an industry so consumed with an unwelcomed over assertive masculinity resulting in a gender imbalance worse in 2017 than in 1913, as The Guardian reported in September. Taking a focused look at The Levelling, its lead character is a young independent veterinary student who is faced to return home after she receives a tragic call informing of a family suicide.

The devastation caused by her brother’s death is embodied in a destructive flood, which has damaged the farmland and livestock. Such floods leave their physical devastation in the surrounding landscape, still Leach utilises a stark juxtaposition of animals filmed struggling for dear life behind a void of blackness and water to draw further attention to their damage. Adopting some cinematic panache clearly references Jonathan Glazer’s masterful Under the Skin (2013; pictured above) and Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice (1986; pictured below) , yet underlying this, is an innovative representation on an environmental crisis that left the local farming community in a state of sheer dismay.

Such a minimalistic and surrealist approach is rarely seen in contemporary British film, only serving to highlight Leach’s very creative filmic approach. Through this void of nothingness, the rural community are truly isolated from the rest of society; foreground outside the context of The Levelling in a report documenting the Environment Agency’s neglecting of Somerset rivers. The neglect held at Parliament transpires is filtered in an expression European influences. Reading the void in a psychological light, its blackness emphasises Elle’s brother’s fragility of mind, resulting in his decision to take his own life. The antithesis of the idyllic countryside, soon to be seen in Downtown Abbey’s jump to the big screen, The Levelling’s setting and focus on a lower- middle class awash with a daily struggle evidently displays a Britishness which isn’t not so jolly, secure or pastoral after all.

.

British boys don’t cry

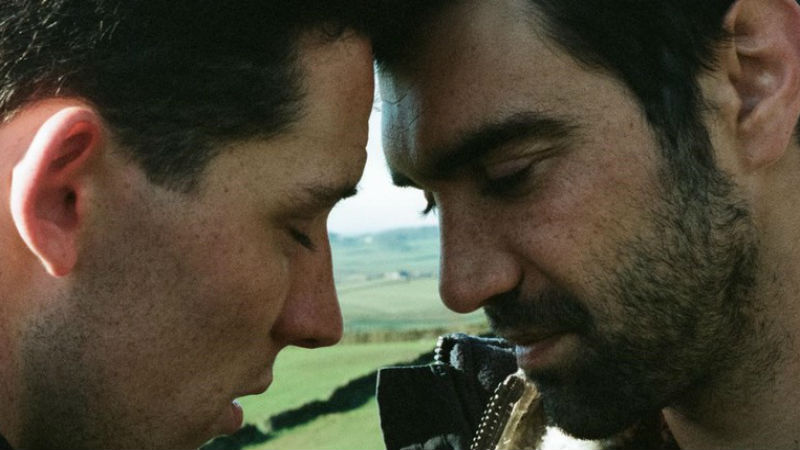

The fragility of British masculinity and adoption of European styles comparably permeates God’s Own Country (in the two pictures below). Inviting an aesthetic compassion to Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights (2001), the cinematography captures the Yorkshire moors in an pure fashion; it evokes every human sense we hold through sight and sound. Chiefly in repressing his sexuality, Johnny Saxby (Josh O’Connor) forces himself into stealthy sexual acts and drinking his woes away.

Forced to take up his father’s position on the farm after a stroke, life is a constant slow movement in a sea of grey for Johnny. Employed as an additional pair of hands, Romanian worker Gheorghe Ionescu (Alec Secareanu) lives an unstable life of physical labour upon different farms across the county. Forced to work together, in order to preserve the farm, Johnny comes to adore Gheorghe in time through his loving care and attention. Escalated by an understatedly aggressive performance by O’Connor, God’s Own Country’s protagonist typifies the much too prominent reserved sense of British masculinity. In every movement, he appears to be exerting every sinew in his body. Failing to express his emotions freely has been detrimental to his life as whole, granted until Ionescu has entered it. Firstly, against his presence at the farm, clear racist and far-right ideologies are held towards Gheorghe. Johnny’s colloquial racial slurs are accentuated by the geopolitical context of contemporary Britain.

Not an outright Brexiteer, it’s not misinformed to suggest that the lead character could have easily been swayed by Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and et al’s promise of an extra £350 million a week to reinvested into the NHS, something which Farage himself has stated as a regretful pledge. Pre- and post- Brexit hence consume the undertones. Lee’s ultimate message of transforming hate to love is a message that should be embraced by all. Roger Ebert’s Glenn Kenny cites God’s Own Country a “a tricky movie, but not in a way that’s dishonest. Its first feet are in the school of miserablist realism” – thus linking to the verisimilitude of Bruno Dumont and his French contemporaries. Though a simple link in their approach to filmmaking, it cannot be ignored that God’s Own Country’s authenticity of working life, accompanied by a sound design which leaves one feeling cold, is pivotal to illustrating a class familiarly seen abroad and not in UK features.

.

British and beautiful

The distinctions between fiction and reality are blurred in the deep focus God’s Own Country and The Levelling pay towards presenting a rural community who speak more to what Britain and Britishness is in 2017 than any UK produced film this year. Yes, they do use European styles and cinematic language, but what is created by Lee and Leach are entirely British and beautiful pieces of film. A sense of duality lingers over any final comment; beautiful creations have been made through illumining a class who hold some of the most prevalent problems in modern society.

Sean Martin’s essay ‘Seven Elements of a Tarkovsky Film’, states that “Tarkovsky is essentially proposing giving the audience time to inhabit the world that the take is showing us, not to watch it, but look at it, to explore it. A film, therefore, is not an escape from life, but a deepening of it”. And this is is precisely what Lee and Leach achieved in their two films, with such a poignant representation of British rural communities.

After God’s Own Country’s success at the BIFA Awards a week ago, taking home best sound (Anna Bertmark), Best Actor (Josh O’Connor), Debut Screenwriter (Francis Lee) and Best Film for 2017, it is welcomed acclaim for a film which deals which our socio-political time and British rural communities in such a nuanced and understated fashion, evidently resonating with BIFA voters.