You’ve got to admire the sheer ambition of Ederlezi Rising, a Serbian Sci-Fi movie shot in the English language with production values and visual effects on a par – mostly – with anything Hollywood at its most lavish can offer.

I say mostly because there’s an early rocket launch sequence which cries out for exterior shots of the rocket on its launch pad and then taking off, but all we get is an admittedly impressive view from space of the distant ship ascending into the atmosphere. It’s the only time the production misses a trick like this and it doesn’t detract from what follows.

The plot concerns one man and his dealings with women – well, one woman in particular. Milutin (Sebastian Cavazza) is given a new assignment by the Ederlezi corporation. Prior to his flight into deep space, a woman social engineer (Marusa Majer) explains the nature of his mission and that he’ll be required to work in a team of two, the other member being an android modelled after a human woman “but unlike a human woman, she’ll be unable to hurt you.”

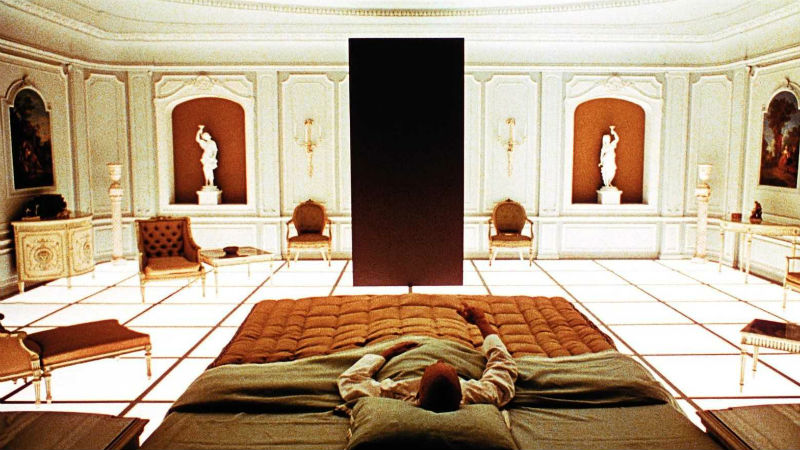

In other words, he gets to programme the android, so in addition to doing her work as a crew member, she’ll do whatever he wants. Cue much physical, sexual activity between Milutin and his android Nimani (former porn star Stoya) whose name appears to be a generic model branding rather like HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968).

In the long tradition of Sci-Fi going back to ‘Mother’ in Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), the ship’s computer is also a woman (voiced by Kirtsty Besterman). But it’s Nimani with whom Milutin spends the most screen time. When she periodically and literally shuts down her battery to recharge, she stands upright while lines of orange run up and down the three walled sides of the square shaped charging station around her recalling nothing so much as the black and white image of circles running up and down the lifeless, upright robot Maria in Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927).

Although she is very much an equal partner in the two-man crew operating the ship, Nimani’s heavily sex-oriented extracurricular activities recall the sexualised androids of Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982) and its sequel Blade Runner 2049 (Denis Villeneuve, 2017).

The other major reference point is Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1971), the space station interiors of which have clearly provided the inspiration for those of the ship here with its sparse angular passageways.

There are further links. Solaris‘s astronaut was obsessed with and repeatedly ran into a reincarnation of his late wife while Ederlezi Rising’s is a loner obsessed with his numerous previous failed relationships with women. This contrasts with Nimani over whose personality Milutin has some control, but she proves far from satisfactory because ultimately he wants a partner capable of her own decisions, even if they prove to be at odds with his.

He can enable her independence only if he can delete her operating system and then reboot it, leaving her with memories generated from their relationship but without the compulsion to submit to him. The ship’s computer refuses him the security clearance needed to action this, so Milutin has to find a way to override the system. His only option is to put the ship in danger to access the required clearance. But in doing so he’s warned that the uninstallation process is irreversible and will be potentially catastrophic for Nimani.

There are more than enough CG exterior spaceship shots to satisfy SF buffs, but far more importantly the relationship material tackles some very deep male/female relationship issues. The whole thing is surprisingly memorable and effective.

Ederlezi Rising plays in the Raindance Film Festival. Watch the film trailer below: