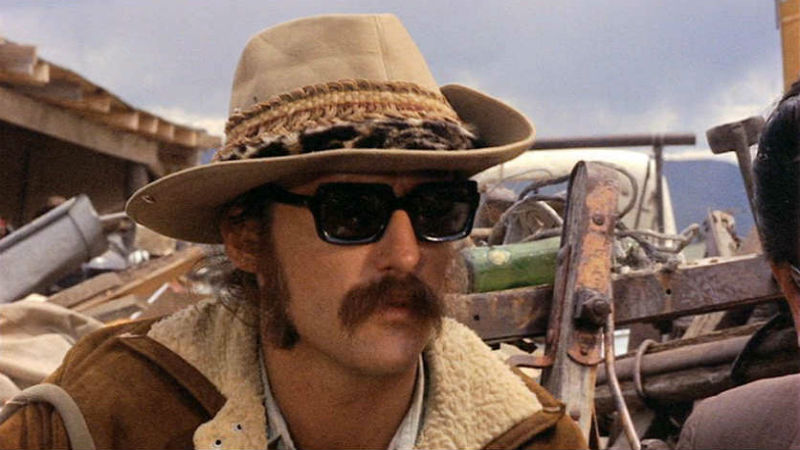

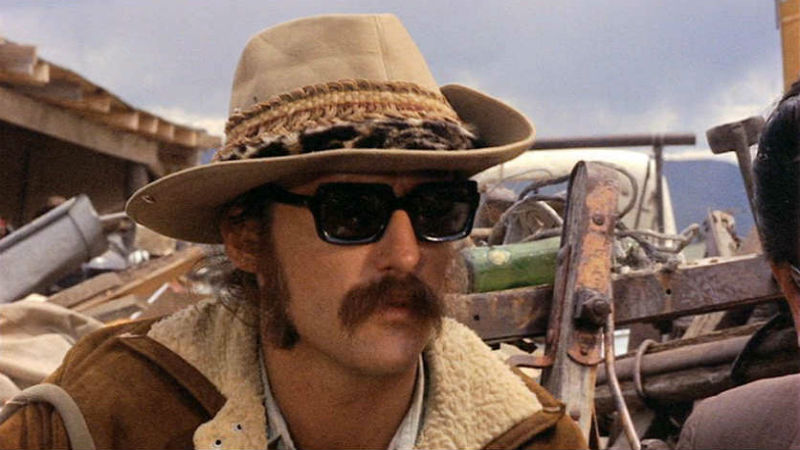

No movie crystallises the time and place in which it was made quite like Dennis Hopper’s 1969 road odyssey, Easy Rider. The film reflects on the schism of war and peace that permeated America in the 1960s. Watching it today, the stench of reefer smoke, stale sweat, beer and the boiling asphalt of the long highway linger on as the film’s two heros Billy (Dennis Hopper) and Wyatt (Peter Fonda) drift across the American landscape, chasing down the American Dream on their custom-built motorcycles. There only goal is to get rich, get loaded, hit the Mardi Gras in New Orleans, and as Billy exclaims, “retire in Florida”. They call this land home, but the county, at least the mainstream aspects of society, is done with them and their kind. They are the US’s lost sons, rebellious, done with the hokey past and waiting for the future to be born, whilst not actively participating in it.

For the most part, one could watch Easy Rider today through the prism of nostalgia for a more innocent time, one that most viewers of the film would not have even lived through. An almost hopeful and naive optimism runs through the narrative of the film. The optimism is obviously misplaced and its makers know this for the film offers an underlying sadness, a futility in existence, and the improbability of ever living in a truly free society. For example, when Billy and Wyatt encounter a hippy commune basking in the hot desert and watch as they plant there seeds into a rugged dry hilltop, Wyatt declares that their harvest will be successful and they will prevail, even though the odds are stacked high against them. Billy, ever the pessimist, knows they are doomed to starvation and failure.

.

Oblique criticism

Easy Rider never directly comments on the true-life circumstances the country was facing at the time; the Vietnam War, the Cold War, riots in the streets of every major city, a President shot dead at the start of the decade.

These events are not witnessed nor spoken of. And the film does not comment on the positive aspects of 1960s’ America; the women’s liberation movement, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ending racial segregation and discrimination. Not only this, but the cultural shifts and events that were peppered throughout the decade that would come to fruition in the following decade (I’m thinking here of Woodstock, Roe v Wade). In Easy Rider’s worldview they did and didn’t happen, or perhaps it just doesn’t matter either way.

At least on the surface, the visual beauty and vibrant colour of Easy Rider did not portray a country in turmoil. Cinematographer László Kovács is perhaps the unsung hero of the piece, effortlessly opening up the spaces and letting the film draw in huge lungfuls of air and lingering on bright and vibrant colours. This is what separates Easy Rider from its biker-movie brethren; the sense of space and time spent rambling down empty freeways gives the film an expanse that engulfs all. Yet underneath this bright and shiny veneer the rot is clearly setting in, as witnessed by the opposition that Billy and Wyatt encounter on their travels. When they pull up to a motel on the freeway, the sign suddenly changes from ‘Vacancies’ to ‘No Vacancies’. They are not welcome. When they enter a roadside cafe, they are faced with a torrent of vulgar abuse concerning their ‘hippie’ appearance and attire. Only in New Orleans are they welcomed and this possibly has a lot to with the expenditure of cash stolen from George Hansen’s battered body (the hicks from the diner extract their revenge) on drinking and dining in a New Orleans pleasure palace.

.

Riding into the 1970s

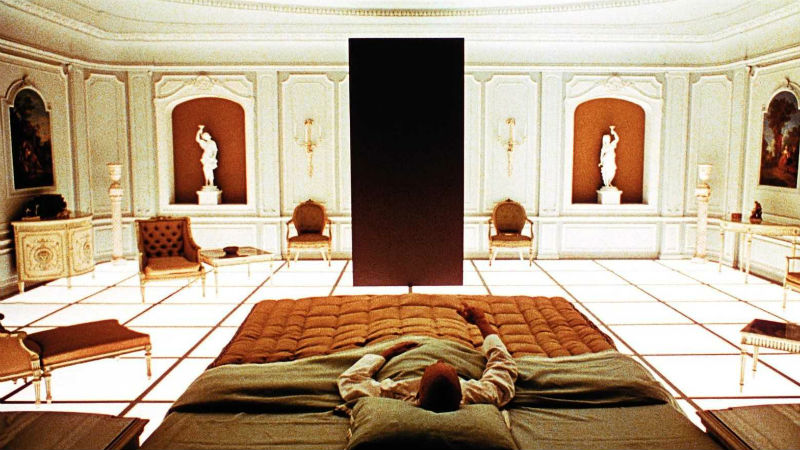

Easy Rider makes it very clear that our heroes are a part of a demonised and unwelcome tribe. It was a monumental little movie that generated enough heat, vision and revenue to change the direction of Hollywood, and independent movies alike, for the foreseeable future anyway. The film allowed the New Hollywood ethos to fully engage and for small auteur movies to be made in the early 1970s, such as Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces (1970) , Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), Monte Hellman’s Two Lane Blacktop (1971), and, of course, Dennis Hopper’s own ill-fated Easy Rider follow-up, The Last Movie (1971). The influence would also reverberate into the 1980s and beyond as smaller movies were steamrolled by the Sci-fi mega-blockbusters of Lucas and Spielberg and their ilk. Oddly enough, students of the New Hollywood themselves. Filmmakers such as David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino would look to Easy Rider’s DIY ethos, if not its exact content, to find success in making independent movies in this era.

For example: the film’s all-conquering soundtracking signalled a new and dynamic approach by incorporating already known and popular rock and folk songs into the mix. Tarantino obviously took extensive notes from Easy Rider when soundtracking his own movies in the early 1990s.

The songs included on the soundtrack to Easy Rider lighten and darken the mood where appropriate with songs such as Steppenwolf’s The Pusher and Bob Dylan’s It’s Alright Ma (I’m only Bleeding) casting a grim, deathly shadow over the narrative, whilst Fraternity of Man’s reefer anthem Don’t Bogart Me and The Holy Modal Rounders’ bizarre and joyous If You Want To Be A Bird allow for humorous moments to unfold.

Although in their early-to-mid-thirties, Hopper and his cohorts understanding of youth culture was clear in the choice of music. Every song in some way corresponds with the visual elements. It’s now impossible to hear Steppenwolf’s Born to be Wild or The Byrds’ I Wasn’t Born to Follow without envisioning Billy and Wyatt rambling across the American landscape.

.

The summary of an era

With all the weight of trying to define the era, it is easy to forget that it is often the improvised campfire interactions of Hopper and Fonda, and later, when they are joined on the road by Jack Nicholson’s George Hanson, which drive the loosely tied plot together. The ad hoc conversations provide some invigorating black humour and insightful, if slightly undeveloped, observations (“I mean, it’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace”). Without this content Easy Rider could have easily become another exploitation biker movie, it is credit to Hopper and Fonda that they saw an opportunity to use this tried and tested format to also summarise an era.

Following the success of Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda began to distance themselves, both personally and professionally, from one another. A disagreement with screenwriter Terry Southern and between themselves over the authorship of Easy Rider’s screenplay was never fully resolved and fractured the relationship and artistic partnership. Fonda showed up fleetingly in the background of Hopper’s The Last Movie, but after that film, their on-screen alliance was severed forever. A shame as their onscreen partnership and offscreen friendship seemed genuine and relaxed and might have produced more films.

.

Make America racist again

Easy Rider is far from perfect. Fifty years on from its release, what has changed? In fact not much at all and Easy Rider, and its director are partly responsible for this sense of stuckism. In the US, President Donald Trump is by and large a broadened out version of the small-town hicks Billy, Wyatt and George encounter at the roadside cafe. No prejudice is left behind. Immigrants, refugees, feminists, the poor, the political left, the unions. Anything ‘other’ is ridiculed as inauthentic and unAmerican to the proposed progress of American might.

In dialogue set round the campfire, George Hanson recalls that “this used to be one helluva good country,” and then goes on to talk about personal freedom. Trump’s campaign slogan of “Make America Great Again” and Hanson’s point evokes the same principle of looking backwards to a time when America was prosperous and in control of its own destiny. On reflection it’s still almost impossible to decipher what era of American greatness Hanson and Trump are trying to evoke. The assumption is that any era they are discussing is romanticised and vague, at best, and is not any version of America that they ever actually lived through, perhaps never even existed in the first place.

.

Pushing the envelope?

Easy Rider was a fair stab at societal commentary for the time, but despite its gallant efforts in attempting to explain that money does not equal personal freedom and anyone who follows that path is doomed, it’s also a deeply flawed film in that it ignored the plight of anyone other than the white hippy and the professional beatnik. Afro-Americans play no role in the film. They are only seen in passing and marginalised to the side of a road in shacks and shanties.

Despite pushing the boundaries, and in fact breaking some (smoking real joints on camera), there were many more that would have made Easy Rider a more inclusive film and a genuine article of the era of liberation.

To take it on face value, Easy Rider still resonates 50 years on. The content may have dated (though capitalism is an issue that so far has never gone away and still plagues us), but its value as an extraordinary piece of independent filmmaking and game changing use of music and visuals, the incorporation of political and societal commentary, and of course the iconic motorcycles and attire means that its place is firmly held as one of the most important and vital films to be made in the short history of film.

As the tagline for the movie stated: “A man went looking for America and couldn’t find it anywhere.” Fifty years on we’re still looking.

This is an edited and expanded extract from Create or Die: Essays on the Artistry of Dennis Hopper