When illegal human experiments go wrong, an undead test subject escapes from Korea’s biggest pharmaceutical company and winds up at a shabby gas station run by the Park family. Upon discovering their strange visitor, the head of the household is bitten, but instead of transforming into the undead, he is revitalised and full of life. Seeing this the misfit family that spans three generations, hustling passers-by to make ends meet decide to monetise their fountain of youth, and soon the locals are queuing up to be bitten too.

Director Lee Min-Jae describes his feature debut Zombie for Sale (Gimyohan gajok) as, “…a slightly unfamiliar and odd zombie film.” The quirks of a zombie that likes human flesh with ketchup and whose bite revitalises his victims, brands this as one of the more curious entries in the sub-genre in recent years.

Min-Jae flips the tropes of the genre, reframing the monster as a fountain of youth or elixir of life, as opposed to its familiarity as an harbinger of walking death. It’s a creative move, but as he proves, you can only push back so much before the familiar reasserts itself. Zombie for Sale is an experiment in offsetting familiar conventions with the unusual, but the peril the filmmaker faces is from an audience a film of two halves may divide – creativity that descends into the familiar apocalyptic mêlée.

Cinema is saturated with the zombie film, the image or scenes of characters under siege and pursued by the undead a familiar sight. From conversations with critics and friends, I’ve picked up on a feeling that the sub-genre has become tedious. This exposes the irony of the familiar to both attract and repel. For any new addition to the undead canon that wants to appeal beyond the die-hard fan, it needs to repackage the familiar, but is this enough, and is it possible even?

A mix of zom-rom-com, well over half of the film is devoted to the comedy – around 70 minutes in total of its 122 minute runtime. The horror is held until the outbreak inevitably hits, and its here that the filmmakers creativity begins to feel stifled.

The earlier comedy had me chuckling along more than any film has in a while. This is in part due to the emotionally expressive nature of the Korean characters – a friend who has spent time in Korea has told me that they are as passionate and expressive offscreen as they are onscreen. I find there’s something larger than life to the Korean character, truth merged with emotion that feels untruthful and heightened for performance in Western cinema. In Zombie for Sale, such emotionally expressive characters add to the appeal of the comedy and charm of this dubious family of hustlers.

There is a lack of character development, but Min-Jae shows the effectiveness of sparing character detail, particularly for Hae-Gul (Soo-kyung Lee), the daughter of the family, who confides in their undead guest, her love interest about her mother’s death during child-birth. A seed of information replaces her dramatic arcs, re-surfacing to have the chaos resonate for her on a personal level. Similar touches for the other characters would have been welcome, although the characters serve their purpose, provoking a mix of laughter and suspense.

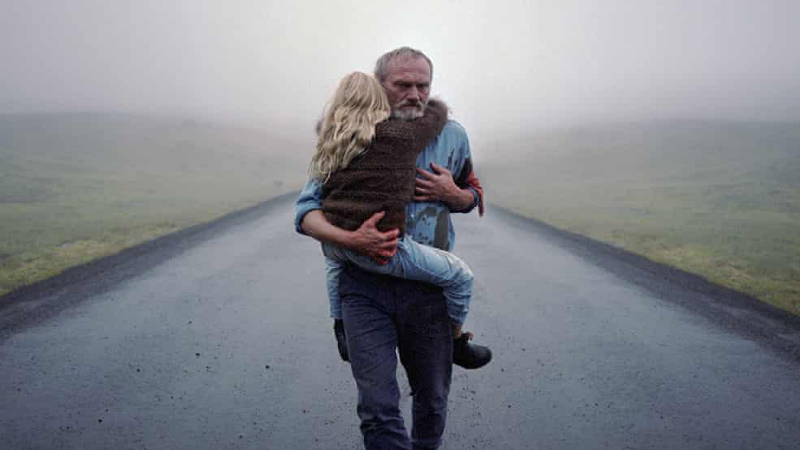

What is striking is that the earlier visual expression of the budding romance conveyed through a visual style or language, feels new to the sub-genre. It channels a modern expression of silent film, that merges painting, photography and cinema, an aesthetic rarely championed in this type of genre storytelling. Here is a filmmaker that conveys his appreciation for expressing feeling in cinema through image and sound, not exclusively dialogue or text, showing glimpses of an artistic flourish in which film as art leaps above film as an exclusive narrative form.

One wishes the filmmaker had continued to flip the script, but even before the genre reasserts itself and the apocalyptic mêlée begins, we find ourselves questioning what the film is and what it wants to be. It is difficult to push back against a sub-genre with such a firm, even self-conscious identity, and so, the director is right to say that it’s a, “slightly unfamiliar and odd zombie film.” Yet it’s also a product of our contemporary world because amidst the current pandemic crisis, Min-Jae’s film has an allegorical presence of mind. In another time it may have been more escapist, but in this current time the film resonates disturbingly because when one looks to the U.S, an ally of South Korea, the film can be seen as a satirical piece of storytelling – the priority of capitalist and economic needs over containing a potential contagion. Zombie for Sale is a reflection of present day anxiety, a snapshot preserved for posterity.

Zombie for Sale is out now on Blu-ray and is streaming on the Arrow Video channel.