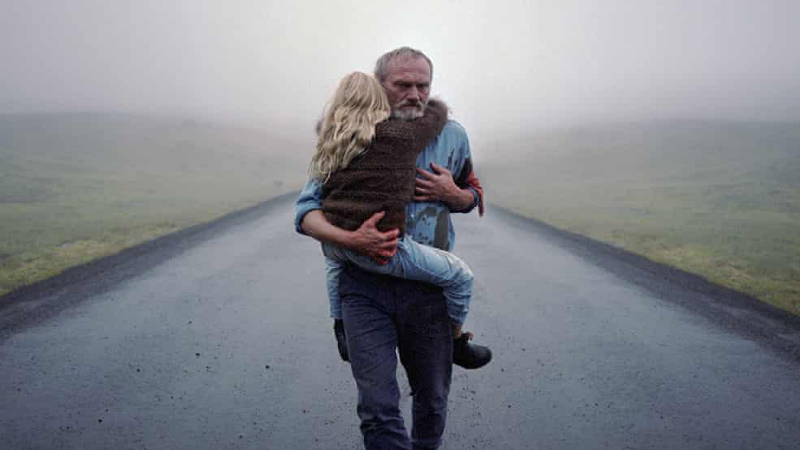

A remote Icelandic town is the setting for an obsessive search for the truth, when off-duty police chief Ingimundur (Ingvar Sigurðsson), begins to suspect a local man of having had an affair with his late wife.

A White, White Day (Hvítur, hvítur dagur) is the second feature from director Hlynur Palmason, and features shades of his 2017 feature debut Winter Brothers (Vinterbrødre). The ratcheting up of tension as Ingimundur becomes increasingly obsessive, ultimately placing his granddaughter in harms way by confronting his wife’s lover, mirrors the escalating tensions between two families in his earlier work, while the cold environment also serves to connect the two films.

In conversation with DMovies, the filmmaker discussed his desire to blend past, present and future, working with a cold head and warm heart, and finding humanity in ambiguous cinema.

Paul Risker – Why film as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment for you personally?

Hlynur Palmason – It’s a bit mysterious because I’m like a lot of children who just became interested in the film medium by watching films. I grew up with a very westernised cinema, Hollywood films, and I come from a working class family. We never went to museums or such, but I remember seeing films that were different, and I remember finding it very interesting how it felt different and personal – how it connected with me very strongly. I’ve always been extremely obsessed with images and sound, and putting them together to create an experience. So from an early age I began working both in photography and in painting and drawing, then with the film medium.

PR – Has the filmmaking experience influenced your appreciation of film, and changed the way you watch films?

HP – It can change a lot because when you adore or spend all your time on something, you become very passionate, you speak your mind, and you have very strong opinions. This happens naturally, and I remember reading the diary by the French painter Eugène Delacroix. He was out seeing a concert with a very well known pianist, and in the first ten seconds he could easily tell if he was going to like it, because there’s a temperament and there’s a personality in each tone, and it’s the same with film.

When I watch a film, I immediately know if this is something interesting or something I find mediocre. It’s a strong word, but I absolutely find that this changes with time – you become more interested in things that are maybe a little more difficult, or a little more open. When I watch or experience a film, I need to be respected – the film needs to be a little open, and there has to be space for me to enter and have my own thoughts. I don’t want someone to dictate what it is exactly that I am supposed to feel – I have to put my own self into it.

PR – What was the genesis of A White, White Day?

HP – I was always inspired by the studio or the interior life, like with artists, and of each stage diving deeper into the process. I always wanted that for myself and felt that was the right path. The day starts for me with taking the children to school and then working all day, which is basically diving deeper into what you’re interested in, and I tend to use everything around me.

My films and my process are very much a blend of the past: where I come from, my roots, then the present: what I’m fascinated about right now, my temperament, and how I see and hear things, and also the future: those things I fear and desire, what I’m exploring, and the dreams. I like it when my films become these three things blended together, and that’s personal cinema, and that’s what I’ve always wanted.

With A White, White Day especially, there was this beating heart of the film that I was interested in, of these two kinds of love: the unconditional love towards a child or a grandchild which is simple, or a more complex love towards a lover, which is something completely different. I wanted to explore these two things, but it didn’t work until I found the world to put it in – this white world. You have all of these things going on and sometimes it feels like they are all pointing in the same direction, and you’re filtering out the things that fit and don’t fit, and it’s so strange.

PR – The opening quote infers a possible supernatural element to the drama, but these expectations are subverted. Would you agree that the film is balancing itself between different types of stories?

HP – It’s always this fine balance. It’s almost like a piece of music: there is a little bit of warmth and then it becomes a little bit cold, then it goes up and then down a little bit, and then it goes over there, but not too much. It’s always this balance I am working with, and the quote is also a big part of that balance.

How do people categorise the film? Do they say it’s a mystery? Do they say it’s a drama? They have all of these titles that I don’t even understand and I know very little of genres to be honest, so it’s always interesting when people are trying to find a shelf to put it on. I like it when the film is more fluid, moving around and not settling on anything.

PR – In this drama, the past remains a haunting present as a secret is revealed, the story mirroring your reference to diving deeper into what interests you. Is there a intuitive dimension to your process?

HP – I love this blend of past, present and future coming together at the same, and when it works, it lifts the experience. I’ve always tried to somehow make that work. I love how things can sometimes surprise you when you see objects and you film them, and you don’t know why, but you have a certain feeling that they do connect to a certain thing. I just try to keep my head cold and my heart warm, and to go intuitively with what feels right, by following the things I want to do and experience, instead of thinking about scenes that explain so the audience understands something. I’ve never really spent my time on those kinds of things because it has to be from the want and desire to make it. Those individuals that have experienced the film will feel the same energy as the filmmaker who is making it, and it’s very important, especially with films like this that people feel that they’re being very honest and truthful, and they’re trying to open up a dialogue and be expressive. All of these things are very important if you’re making cinema, and you’re probably doing it because you want some kind of dialogue and you want to be part of something, because I think everybody does.

PR – As much as you say you want the audience to have a dialogue with you, are you also entering a dialogue with yourself?

HP – I try to experience the film through me. Unlike many films that are preconceived concepts, almost like a product for people, that have gone through many test screenings where people will tell them if something isn’t clear, or they don’t feel enough for a character, we definitely don’t do that. We use ourselves, and I’m talking about the crew – we take it in and feel it, and whether it feels right and we think it’s ready is very much a gut feeling.

My editor and I are sitting together for eight months and we never talk about plot or anything like that. We talk about the breath of the film, the way it moves and the tempo. It’s like a composition, much more like a rhythm.

There are some films that you want to see again because there’s more meat on the bones, there’s more things to explore because there are a lot of questions. I don’t know if it’s a crazy thing to say, but I feel that the films that have an ambiguity or seem to have another level, they have so much humanity in them, and I think that’s probably what I’m aiming for. Every time I start working on a project, all of these plot driven points or the story just naturally disappear because I’m not really interested in them. I tend to just go after what I’m fascinated by: the faces, the movement of the people, how they talk and what they talk about, and how the landscape around them shapes them. And suddenly I’m just focusing on these things because we don’t really have plots in our lives – things just happen.

A White, White Day is streaming on Curzon Home Cinema, Peccadillo Player and the BFI Player from Friday, July 3rd.

The image at the top is of Hlynur Palmason; the image in the middle is a still from ‘A White, White Day’.