The 71st annual Cannes International Film Festival starts on May 8th for 12 days, and the programme has already been announced. The event continues as auteur-driven, internationalist, prestigious, innovative and, of course, anti-Netflix as ever. The Festival demands that all films in the programme get a theatrical distribution in French cinemas, which caused the streaming giant to pull out last minute, just before the programme was announced.

The list is teeming with big director names from all parts of the planet, and the Competition alone includes eight newcomers, from a total of 21 films selected. A jury under the presidency of Cate Blanchett will announce the winner. A grand total of 1,906 feature films were viewed by the various selection committees. At least 100 movies have been announced for the various sections of the Festival so far: Un Certain Regard, Director’s Fortnight, Critic’s Week, Classics, Special Screenings, etc. Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s psychological thriller Everybody Knows will open the Festival. The Official festival poster (pictured above) features Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 film Pierrot le Fou. It is the second time festival poster was inspired by Godard’s film after his 1963 film Contempt just two years ago.

Below is just the the tip of the iceberg. Our very dirty picks, films that we think you should be looking out for. Don’t forget to follow us for live updates at the event, as we watch the films below and reveal they were worth the wait.

.

1. Climax (Gaspar Noe):

The Argentinean provocateur, who has worked most of his life in France, returns three years after the 3D explicit sex romance Love. which saw an actor ejaculate on the audience and the camera assume the penis perspective as it enters a vagina. Everyone is curious what antics the enfant terrible has under his sleeve the time, and whether audiences will leave the cinema feeling orgasmic. The movie is in the Director’s Fortnight section,

2. The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (Terry Gilliam):

Terry Gilliam’s long-delayed feature will be the Festival’s closing film. Production began exactly 20 years ago (!!!). And yet the film encountered new problems, and a legal challenge almost prevented it from being shown this year. The movie is a blend of fantasy, adventure and comedy loosely based on the Spanish super-novel Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes. The film, which is pictured below is in the Competition.

3. Pope Francis: A Man of His Word (Wim Wenders):

The 72-year-old German filmmaker has largely focused on producing and directing documentaries in the past couple of decades, including the iconic Buena Vista Social Club (1996) and Our Last Tango (2017, directed by German Kral). This time he has created what looks like a romantic portrait of the current Pope, in which he speaks directly to the people. The film is also in the Competition. Let’s just be grateful he didn’t do a film about his countrysake and previous pope, aka God’s Rottweiler. Meanwhile, Wenders has a feature film coming out in cinemas later this year.

4. Donbass (Sergei Loznitza):

The Ukrainian director’s previous film, a creepy tribute portrayal of Russia, A Gentle Creature is showing in cinemas across the UK right, and one of the dirtiest films you could catch right now. The film was in the Festival’s Competition last year. This year, the director returns with a film named after the region of the Ukraine that Russia recently attempted to annex (although Putin will dispute this). We would hazard a guess that the new film, which is in the Un Certain Regard section, will be no more sympathetic of the largest country in the world.

5. Three faces (Jafar Panahi):

The Iranian director of The Mirror (1997), Offside (2006) and Taxi Tehran (2015) started his career in the 1990s as the assistant director of the late Abbas Kiarostami. His films often dealt with controversial and fiery topics (such as women attending football matches in Offside), and the director himself was arrested in 2010. Three Faces is described as a “mountain travel” film, and it’s in the Festival’s Competition

6. Shoplifters (Hirokazu Koreeda):

Firmly established as one of the most prolific and creative voices of Japanese cinema, the director of the dirty gems After The Storm and The Third Murder (both released last year) returns with Shoplifters (pictured below). The film, similarly to After The Storm, focuses on a dysfunctional “family”, as a group of petty criminals and crooks take in a child from the street.

7. At War (Stephane Brize):

Perrin industries decide to shut down a factory and fire 1,100 employees, despite record profits and huge financial sacrifices on the part of the lower employees. The 52-year-old French helmer once again exposes the ugly face of capitalism, corporate values and labour rights in Europe, after dealing with the subject two years ago in The Measure of a Man. Also in the Competition.

8. Everybody Knows (Asghar Fahradi):

This psychological thriller will open the 2018 Festival, and it features Spanish actors Javier Bardem, Penélope Cruz and Argentinian Ricardo Darín. The double-Oscar winner refused to travel to the US last year in order to collect his statuette for The Salesman, in retaliation to Trump’s racist and Islamophobic government. The new drama Everybody Knows, which we expected to be as profound and multi-threaded as his previous films, the first time the director works in Spanish language, and it’s also only the second time a Spanish language movie opens the Festival.

9. BlacKkKlansman (Spike Lee):

Spike Lee is back, and he’s ready to set fire to his increasingly racist and reactionary homeland. The film follows the first African-American police officer to infiltrate the KKK, back in 1979. The urgency of the movie cannot be overstated. Hopefully Lee will not slip into platitudes and sexist cliches, unlike two years ago with Chi-Raq. In the Competition.

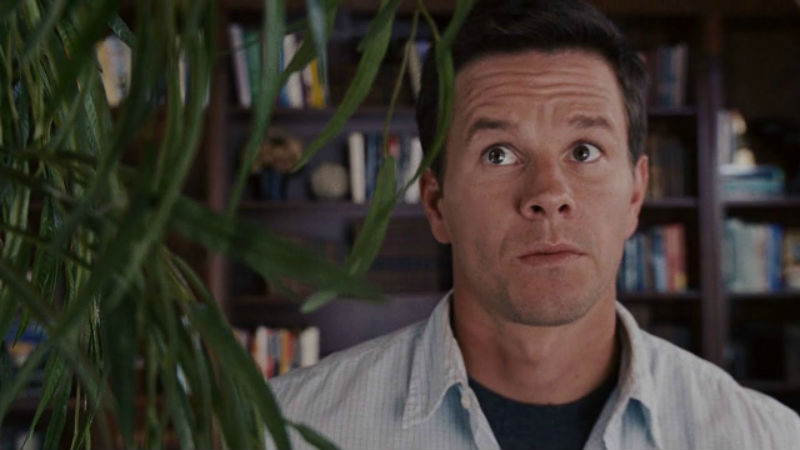

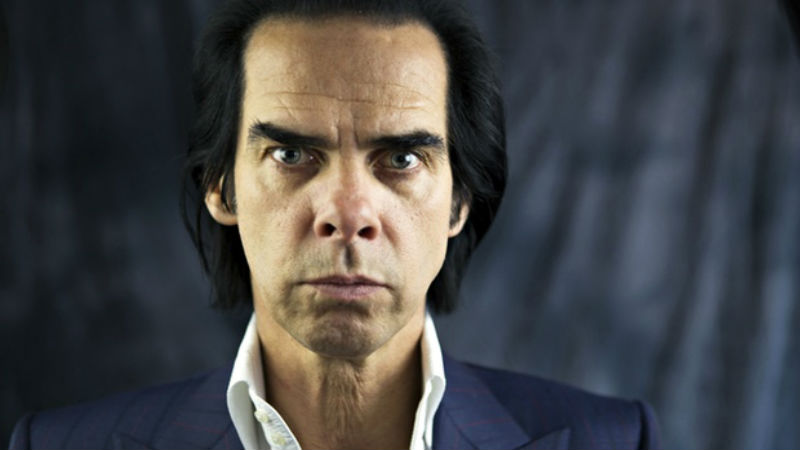

10. The House that Jack Built (Lars von Trier):

The staunch persona-non-grata has now made piece with the Festival, after being banned “for life” in 2011 following some controversial remarks about Hitler’s good qualities. His new film, which is named after an English nursery rhyme, stars Matt Dillon and follows with a highly intelligent serial killer. Von Trier described the film as celebrating “the idea that life is evil and soulless”. The film is running our of the Competition.