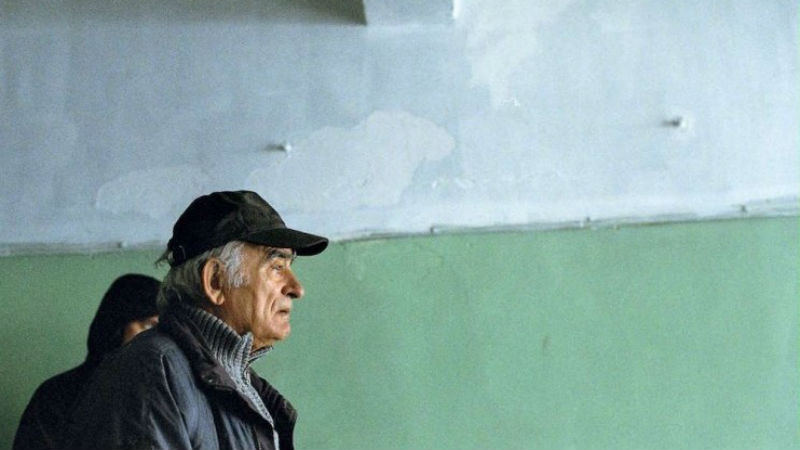

A group of German construction workers are sent to the deep Bulgarian countryside next to the state’s Southern border. All but one of them approach their visit with the preserved hostility of European post-Cold War stereotypes and dynamics. The exception here is Meinhard (Meinhard Neumann), a quiet and private middle-aged man who, despite the language barrier, prefers the company of the locals.

The Bulgarians, we soon learn, are no less prejudiced when it comes to newly arrived strangers. Caught in the timeless capsule of their village, the last time the locals remember seeing Germans was during the Nazi occupation of WW2. Despite the contrasting sentiments, a bond is eventually forged. Meinhard befriends one of the locals, Adrian (Syuleyman Alilov Letifov), and we witness the formation of a special relationship between two men whose willingness to connect and understand one another defies verbal communication.

In contrast to the harmonious microcosm Meinhard is trying to create, tension gradually builds up everywhere elsewhere in the movie. Eventually, a conflict between “occupiers” and “occupied” occurs, when the Germans and the locals have to share the scarce water in the village.

The film examines a heavily male-populated and patriarchal society, offering some sensitive insight and debunking myths. The macho-men chasing foreign girls on a river bank we see at the beginning are entirely deconstructed in the end of the film. While keeping male experience as central to the world of Western, Grisebach successfully portraits the private worlds and psychological complexities of all characters. Ultimately, no one is as weak or strong as they seem, and there are no vigilantes.

By depriving the film of non-diegetic sound, prioritising individual experiences over script, and casting non-professional actors from (except for a very professional stunt horse), Valeska Grisebach creates a cinematic piece so deeply rooted in realism that it transcends everyday life, in the Bazinian sense. Western is a very European movie. It’s literal and poetic. It accurately portrays the boundary between East and West, and – perhaps most importantly – it demonstrates that no barrier is unsurmountable.

Western was out in cinemas on April 13th. It’s available on all major VoD platforms on July 9th.