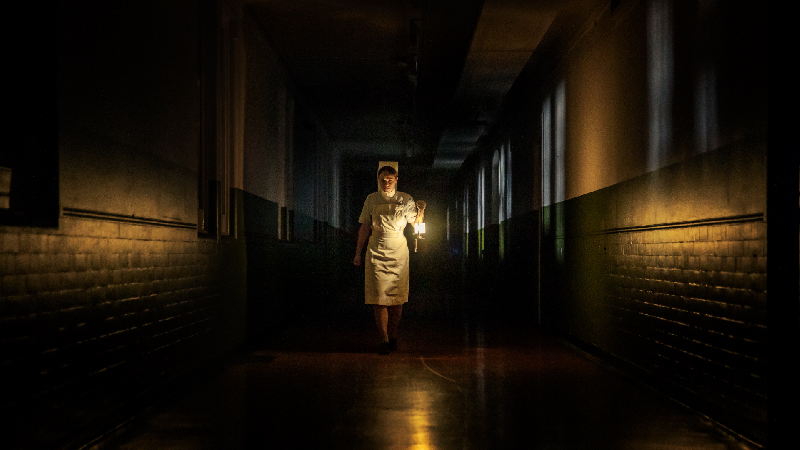

In Damian Mc Carthy’s feature debut, the Irish horror film Caveat, Isaac (Jonathan French) receives a sinister proposal from his landlord. It’s one that risks leading him down a precarious rabbit hole he may never escape. His instincts tell him to be cautious, but the lure of money, coupled with his ego, assures him he can handle the situation. He agrees to look after his landlord’s niece Olga (Leila Sykes), for a few days. His original suspicions that this was too good to be true are confirmed, when he learns she lives in an isolated house on a remote island, in picturesque Cork, Ireland. The only access is by boat, and Isaac can’t swim. Once in the house, he’s then instructed that he must wear a leather harness and chain that restricts his movements to certain rooms.

The filmmaker’s debut feature is predominantly set in the isolated house. His earlier shorts, He Dies at the End (2010), Hungry Hickory (2010) and How Olin Lost his Eye (2013), all offered practice at isolated and claustrophobic trappings, precursors to his more adventurous feature.

In conversation with DMovies, Mc Carthy discussed the influence of Hideo Nakata’s original Ringu (1998), and provoking fear through confusion or ambiguity.

….

Paul Risker – ‘What we are’ versus ‘who we feel we are’ can often be out of sync. I’ve spoken with directors who say that it took a number of films before they felt they could call themselves a filmmaker. Do you feel that you can call yourself a filmmaker?

Damian Mc Carthy – Now, just about. I say that because if I’d ran into a teacher from college when I was making my short films, and they’d asked me if I could come in and talk to the class, I would have had nothing to say. I’m learning how to make films, and I hope I have another 30 or 40 years ahead of me.

Caveat was a very difficult film to make, and every problem we could have had came up. It felt like film school, and so maybe I’ve earned it to call myself a filmmaker now.

PR – François Truffaut said there are three versions of the film – the film you write, the film you shoot, and the film you edit. Would you agree, and would you describe the filmmaking process as a journey of discovery?

DM – I’ve thought about that for years now, and it’s true. You write a film and you think, ‘This script is great, I’m going to make this.’ Then you get into the production and you realise you don’t need a scene, or the actors don’t need to repeat certain lines, and it becomes something different. When you get into the edit, it definitely becomes something else, and that’s what happened with Caveat. It’s not your core story that changes, but how it’s told.

It is a journey because you’re making three different films. I’ll sit down to watch the film when it’s done, and it’ll still be pretty much what I imagined, but it is a journey to get there, and it absolutely evolves as you go along.

PR – I like to think there’s a fourth version, that’s created by the audience. It’s the moment you lose control as the filmmaker, which must fill you with a mix of emotions?

DM – I like that though, and if you’ve ever seen David Lynch asked a question about what happened here, or what did that mean, he gives no explanation. He’s leaving people to watch the film and come to their own conclusion, with their own interpretation. A film is art and it should be up to you what it means.

PR – Similar to a dream or a nightmare, the events that unfold seem to make sense, but the motivations of the characters, and what happened in the past remains shrouded in ambiguity. The film is not about why things happen, but about what happens.

DM – There’s a mystery about Isaac’s past and what’s happening, but a lot of that was very clear in the script. Once you get into the edit, you’re trying to reflect his state of mind, his confusion. He’s not entirely sure what’s happening and there are gaps in his memory. You have to find that fine line between not giving away too much if you really want the audience to stay with him, but you can’t leave them behind in a state of confusion. You have to learn as he’s learning, and that’s just from the storytelling point of view. You’re trying to strip back a lot of stuff to leave people a uncertain about what’s happening, or even at the end of the film, what has happened.

You know that this guy got to the island and he’s got to get off it. If you get that much of the plot, just go along with the rest of it. From a horror filmmaking point of view, there’s something unsettling or scary about confusion. If you’re not entirely sure what’s happening, it puts you on the back-foot. Is this guy a good guy, or a bad guy? Should I be be rooting for him? Hopefully it keeps you engaged and guessing.

A film I loved was Hideo Nakata’s original Ringu. The way he shot the videotape was so strange. There’s a guy with a towel over his head pointing at something, there’s people crawling backwards in the mud. It’s unsettling imagery and none of it’s explained. I saw that a long time ago and I think I tuned into that memory.

There’s something unsettling in not getting an answer to these questions. With Caveat, even though what I’ve been talking about is not visual, by not seeing exactly where Isaac comes from, or what the motivation is, that will hopefully unsettle people a little. You’re not exactly sure who this guy is you’re following.

PR – The score is used sparingly, instead you emphasise the natural sounds to create the suspense. Would you agree that the sound design is the dominant provocateur of fear when watching a horror film?

DM – I always think that if a horror film ever makes you feel so scared that you want to cover your eyes, don’t. Keep watching and just turn off the sound. It’s no longer scary and you don’t miss the plot. The visuals are what they are, it’s the sound where the fear comes from.

PR – You show an appreciation for jump scares, but what’s interesting is your choice to transition from shock to morbid curiosity, the camera lingering on the horror. What was the thought process behind this creative decision?

What you’re seeing with the jump scares and then lingering on them, is me trying to get that balance between hinting at the scare, and letting people’s imagination fill in the blanks. A viewer that has no imagination, they need to see something to be scared. They can’t think of something scary themselves, and so we’re hopefully giving the audience that too. We’re trying to get that balance all the way through the film.

PR – Recalling the idea that there are so many archetypal stories, is it possible to be original, or is originality a little like a box inside of a box – originality inside of unoriginality?

DM – …If you look at Caveat, I tried to incorporate things that I have seen in other films, but hopefully with my own take on it. This isn’t the first film where you’re going to see a man head down into a creepy dark basement. I would like to think I’ve done my take on it – going down in the basement with a drumming bunny in his hand, to see where the end of the chain he’s attached to is going. You can be inspired by stuff, but then you have to put your take on it.

Caveat is streaming exclusively on Shudder from June 3rd.