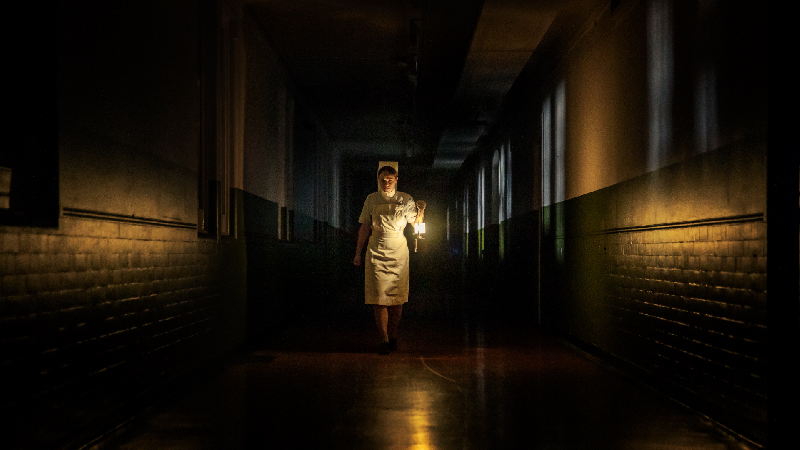

Corinna Faith’s independent British hospital horror is set in 1974, when a period of unrest between the UK government and the coal miners led to a scampering to ration electricity. Trainee nurse Val (Rose Williams), arrives for her first day at the crumbling East London Royal Infirmary. With most of the patients and staff evacuated to another hospital, she’s forced to work the night shift in the dark, near empty building. The walls house a frightening secret that will force Val to confront her own traumatic past, and discover the pain behind the wrath of a malevolent spirit.

Her debut feature, her previous films include the shorts, Ashes (2005), about a father and son who are thrust into a situation, Care (2006), and The Beast (2013), that centres on a young woman’s perilous infatuation with the myth of a beast that stalks the moors. In 2006, her radio production In The Bin for BBC Radio 4 received the Mental Health Media Award for Best Factual Radio. Her documentary work Body-Snatchers (2003), African ER (2004) and Little Angels (2004) have been broadcast on BBC television.

In conversation with DMovies, Faith spoke about the joy of accidentally discovering films, Saturday afternoons watching a film noir, the authored period of British cinema from the 1980s, and how her feature debut is a response to stories of institutional abuse.

…

Paul Risker – Why filmmaking as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or a defining moment for you personally?

Corinna Faith – I’ve always been excited and fascinated by visual images, and just anything to do with cameras [laughs]. I started out as a photography student, and then it just happened that on my degree course we got the chance to try cinematography, and I was offered the chance to move onto the film side because they liked what I’d done. I realised that was my dream come true, but I hadn’t ever reached for it.

PR – We naturally perceive movement even in a still image. Did your photography background give you an appreciation for how in cinema you can create movement without moving the camera, instead using the audience’s imagination?

CF – There was always a crossover in my love of photography and cinema. I’m a film fan in loads of different ways and in lots of different areas, but I’m often drawn to films that have an intense sense of atmosphere, that you may be able to look at something for a while. So that definitely connects to my love of being able to delve into an image, and a lot of the photography that I loved was quite narrative. What I started doing myself was instinctively creating these almost film type images, putting myself in them and setting up little worlds in photo form.

PR – Picking up on your point about having a diverse interest in cinema, what films resonated with you when you were young, and are there any that have particularly nurtured your love of cinema?

CF – When I was young I was very lucky because anyone who’s my age, there wasn’t very much choice, but there were a lot of films on TV. You’d stumble across films in a way that these days, you’d have to seek stuff out, and so you might accidentally watch a film that blows your mind less often because you’re making a lot of choices.

I was often just immersed in some black and white American noir on a Saturday afternoon, or whatever was on. It showed me the massive landscape of classic American Hollywood, and because I was watching my early films in the 80s, quite an authored time for British cinema, I got a taste for the idea that you can create a singular vision.

Besides all the Hollywood stuff, I was watching Peter Greenaway films, and Young Soul Rebels (Julien, 1991) had a massive impact on me at the time. I still absolutely adore Terence Davies.

They’re all so different, but I feel I was lucky that I got that film education just by being sat at home. It’s something I’m trying to pass onto my kids [laughs]. I’m always trying to make them watch something slightly obscure and older to keep their minds open. I feel it was a very fortunate time in that way.

PR – Do you think films not being on tap that created an appreciation that has since been lost in changes with technology and distribution?

CF – There’s definitely something different about the whole experience of how we access and find things. It’s less random and there’s less of, “Oh, I’ll give it a shot and get through it because I’ve got literally nothing else to watch. I spent two hours choosing it at the VHS store, so I have to watch it.” You can get bored and turn off now, but on the plus side there’s definitely a lot of passion around, and there are the curated possibilities like the Film4 movie, and Shudder if it’s a horror. There are people attempting to do the same thing but in different ways, and it’s not the same as the accidental old film noir on a Saturday afternoon, but it’s still good.

PR – You spoke about how the films of the 80s were all different from one another. Looking through your filmography, you’re not leaning in one direction, but seem to be interested in creating a nuanced body of work.

CF – Yeah, I think that’s fair to say. I’m not a horror or genre devotee, I love quite a few particular films across the entire range. I’m quite discriminate in what works for me, and I guess it’s always about being transported somewhere particular with that conviction, and that could be anything from E.T (Spielberg, 1982) to Aliens (Cameron, 1986), or The Shining (Kubrick, 1980) to Paddington (King, 2014). If it has that world you can commit to in that way and be taken somewhere else, then it works for me. I suppose I’m just looking for stories that have enough meat and depth for me to push through and commit, and do what I know it takes to get them made, which is a lot.

PR – Speaking of commitment, seeing a film through requires you to give up a period of your life. What compelled you to believe in The Power and decide to tell this story?

CF – Well that’s the interesting thing because by the time you get to make the film, it has been ages since you first started the process. It has to be universal enough to still be relevant in my own head, and even with this being my first feature, I knew that was going to be the ride because I’d already had one that was not made. In that case I was thinking about people not being heard, and the experience of being a woman and not being heard, which I’m sure is part of the creative journey, as well as the themes of the film.

I was responding specifically to all the stories about institutional abuse that were surfacing like a nightmare into the news at that point in time six years ago. They resonated for me, and I found it incredibly sad in a way that I couldn’t shake off the thought of the lost souls of those places, and those experiences. I wanted to write a ghost story, and all those themes just tied up for me. I thought I was not going to lose interest in this topic because it’s something that doesn’t go away.

PR – Before anything happens we’ve determined that we should be scared. What you create is an uneasy atmosphere in which the music along with the past, the hospital building and the institution agitates our unease and fear, which is then heightened by the supernatural haunting.

CF – What’s interesting to me about this character is that she has reason to be scared even before she steps foot in that hospital. It’s not actually the ghost, it’s a lot of stuff that has happened already, and it’s everything that could happen to her. It’s the nature of the place she’s working for the night, as well as a haunting.

I always wanted the institution and the situation to feel as frightening as the haunting for specific reasons that unfold as the story goes on. I’m glad it felt like that when you watched it because that’s more real.

PR – You mentioned liking to be immersed and taken somewhere else by a film. The effectiveness of the story hinges on us going on a journey with Val, in which we find ourselves lost in her trauma, trapped like she is.

CF – I wanted Val to feel relatable and accessible, and for us to have empathy with her from the beginning. Rose did a brilliant job with that, and it was one of the reasons I was drawn to her.

This is a story about a character peeling away layers of themselves, and going to their darkest place. We all have a dark place [laughs], and we don’t necessarily all want to look at it, but she’s forced to. It’s a big journey for her to go on, and what I love about Rose is that there’s a warmth about her. It’s a real quality she has as a person, and that was helpful as a starting point for that journey, on the surface as well, and where she goes to is quite a different place.

The Power is streaming exclusively on Shudder.