Rose has been a director since the 1980s, when he became known for the original video for Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Relax – the one that was banned, and made the song a hit from club play. He had worked with Jim Henson on The Muppet Show television series and the film The Dark Crystal (Jim Henson and Frank Oz, 1982) previously, and snagged a deal with the BBC. His first full-length feature film as a director was Paperhouse (1988), a cult hit mainly on video, but was well reviewed by several critics, including Roger Ebert, who raved about it when he caught it at a festival.

Paperhouse was made with Vestron Video, which did have some theatrical hits like Dirty Dancing (Emile Ardoline, 1987)but expected to make their money back on video. He is still probably best remembered for Candyman (1992), the most original horror movie of the 1990s. Based on a Clive Barker story, it also had something to say about race and class. Candyman is due for a reboot/remake with Jordan Peele later this year, with Tony Todd reprising his role as the titular character.

Rose did Immortal Beloved (1995) with Gary Oldman as Beethoven, which garnered a mixed response, and unfavourable comparisons to Amadeus (Milos Forman, 195). His next film Anna Karenina (1997) was a tremendous flop. It started a string of films inspired by Tolstoy, but that was the only one set in Russia. Rose followed it up with Ivans XTC (2002), one of his very best, also based on story by Tolstoy but set at the turn of the Millennium Los Angeles. Danny Huston made his name in the lead. It was an extraordinary film, one of the very few that was shot on high-def video before the technology improved that was really good. It’s about the last week in the life of a film agent on a booze and coke bender.

Rose did a few horror films in the late ’00s, plus the Howard Marks biopic Mr. Nice (201) and a film about Paganini. Before Samurai Marathon (2019), his most recent project was an interesting, low-budget Frankenstein (2015) set in modern LA, also starring Huston, who has appeared in almost every film Rose has made since Ivans XTC, including his latest. Samurai Marathon is a Japanese Samurai film set in the Edo period. It’s probably the largest scale film he has done in some time.

Samurai Marathon is out now on VoD. You should be able to find it on Amazon, Apple, TalkTalk TV and the Sky Store (Amazon and Apple are the cheapest options).

…

.

Ian Schultz – How did your newest film Samurai Marathon come around? It’s certainly a change of pace for you.

Bernard Rose – Well, basically, Jeremy Thomas—the British half of the producing team—emailed me out of the blue and asked if I wanted to go to Japan to do a Samurai picture. I thought the answer to that question had to be YEAH! It really was as simple as that, I then went to Japan and met with Toshiaki Nakazawa, the other producer. We got into some discussion about the screenplay they were developing. I then rewrote the screenplay, and then we rewrote the screenplay I wrote into Japanese. That’s the short version, but it was pretty much that. The unusual thing about much of it was me going into a Japanese production, rather it being a Western project going over there to shoot.

IS – Is this the first time you’ve directed for hire, at least in a feature film sense?

BR – Well, in a sense you are always in effect ‘for hire’ if you’re doing the film and are being paid a fee. We spent a good year and a half working on the screenplay, so it wasn’t just like a “here’s the script, do the job” kind of thing.

IS – What was the most challenging part of making a film in Japan, and in Japanese?

BR – It was actually a lot of fun, to be honest with you! It’s interesting to go into another culture in that kind of way. I didn’t know that much about the Edo period when I started the picture, other than what I had seen in movies. I then realised after a while that most of what people know, including the Japanese, about the Edo period comes from the movies. I think in a sense that world of the Samurai has become a kind of mythic arena that has been taken as much from Westerns: Kurosawa was influenced by John Ford. It’s an arena where you can tell mythic stories rather than it being necessarily being restricted to one specific culture, and there’s always been this weird kind of cross-cultural fertilisation in the Samurai movie… between the Samurai movie and the western, certainly. I think all cultures have a weird kind of “Golden Age” mythical path they revert to. In Europe, it’s kind of Knights of the Round Table (Richard Thorpe, 1953), and in America it’s the West, and in Japan it’s the Edo period.

IS – What were some Samurai films you looked at, besides maybe the obvious Kurosawa films?

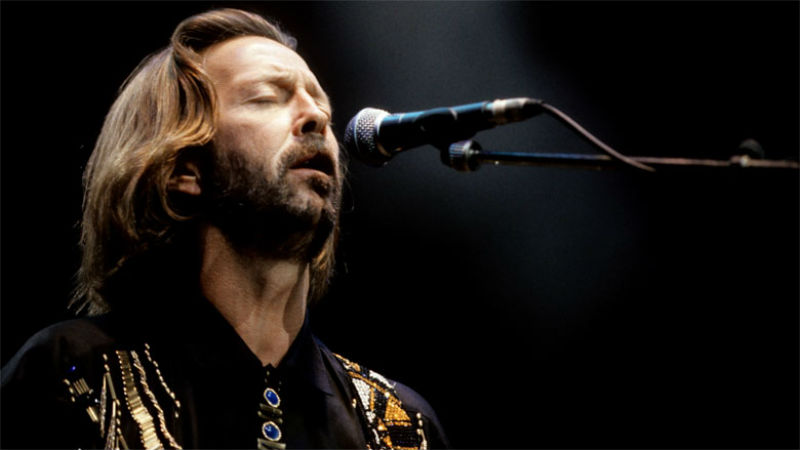

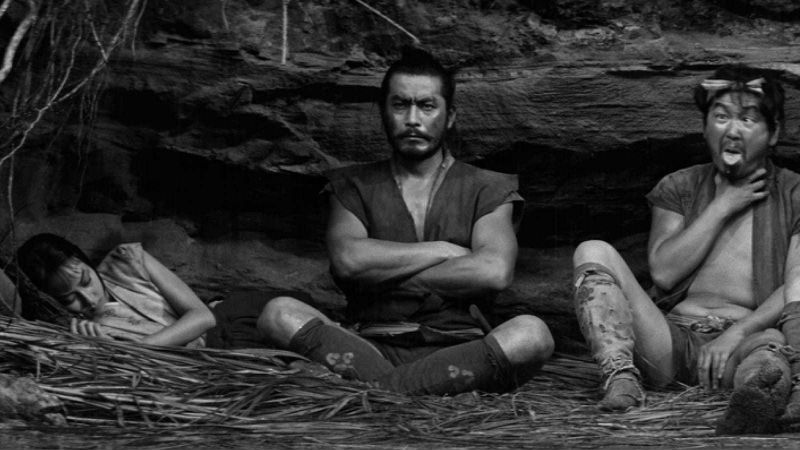

You say we all know them, we all know Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950) and Seven Samurai (Kurosawa, 1954), but they don’t necessarily know the more obscure ones. There are lot of interesting, more recent Samurai films, and some that are in a more classic vein, like Twilight Samurai (2002) by Yoji Yamada and things like that, which has an almost Freudian quality. The things Jeremy and Nakazawa made before such as 13 Assassins (Takashi Miike, 2010), which is much more an action picture, I suppose. The parallels with the Western: one influenced the other, and then it was influenced back. I think Kurosawa came up with the modern concept of violence in cinema with slow motion, which was very much picked up on by Peckinpah, of course. It first appeared in Seven Samurai, and of course Lucas basically based Star Wars on The Hidden Fortress (Kurosawa, 2002; pictured below). It was interesting to go back and inject something a little different—but not making a western film, it’s still very much a Japanese movie.

IS – How was it working with Jeremy Thomas for the first time? Because he seems like such a logical choice for you, with his track record of working with Nicolas Roeg, Terry Gilliam, David Cronenberg, Bernardo Bertolucci, etc.?

BR – He is one of the greatest producers of all time, and is a lovely guy in all respects. He is incredibly helpful and respectful at the same time, two incredibly unusual characteristics for a producer. He is the greatest! What can you say? Jeremy started in the cutting room: he was an editor, so he is very good in post-production too. He just has so much experience and knowledge, and just knows how to deal with people in such a kind of supportive way. He is really the best.

IS – Have you been consulted on the new Candyman movie or not?

BR – Yeah… I’ve had some conversations with Jordan Peele about it but… I don’t think I can tell you anything. It’s coming out this year, and I think it will be rather good, I hope it’s good. I haven’t seen it, and they must be close to being done with it.

IS – When is the remastered Ivan’s XTC coming out?

BR – Hopefully later this year—there’s been some discussions, but we’ll see.

IS – You were a pioneer in digital filmmaking with Ivan’s XTC early on. Do you have any regrets that you didn’t wait till the technology had caught up?

BR – I don’t think it was just about that for me—it was just about the ability to make something that was different in its very nature. Yes, of course the technology has improved massively since then, but the idea you can just go out and make a film with equipment that’s not exactly to hand, but more readily, was more exciting than the technological aspect of it for me. Wait till somebody else does it first? That doesn’t sound very smart.

IS – You made a lot of music videos back during the “golden age,” with most famously the banned Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Relax. What did you learn making videos then that you still use today?

BR – I loved doing music videos. What was wonderful about them, especially in the early 1980s, was the record companies pretty much let you do what you wanted to do, because it was so new to them. It was like making little silent movies, and it was such a great era for pop music, the early 1980s, which was part of what was so fun about it.

I think everything changes all the time, certainly for me. In the videos I made, it was all about visual storytelling: essentially making little silent movies with musical accompaniment. That was also a part of the challenge of doing the Samurai picture. Although obviously the film does have Japanese dialogue in it, I really wanted the picture to pretty much work with visuals and music primarily, and the dialogue was there just to add a little something. I wanted the film to be self-explanatory—there are some films you can understand with the sound off, and some films you can’t. That’s always been a thing for me. You should understand the film without understanding what people are saying. It’s a shame that sometimes with films with subtitles, you just end up reading the movie, because you often miss so much without looking at people’s eyes. What people are saying is never as important as you think it is. When I was cutting the movie, we didn’t have subtitles. It was kind of a slightly different experience when you put the titles on, and obviously you have to, people need to know what’s going on, but there is always less info than you think there is.

IS – Do you see any trends in horror movies at the moment that you find kind of interesting?

BR – The horror business is very interesting, because it’s very cyclical. It’s obviously went through a huge upswell recently, with people like Jordan Peele and all the interesting new directors, and other people too. I think that one of the great things about horror is essentially it’s a way of telling a story that you’re saying to the audience: at least you will get a thrill out of this instead of just sitting through a drama. A lot of the drama and arthouse films I really enjoyed in the 1970s were really horror movies. It’s such a cinematic genre, because you’re expected to make an impact, basically, first and foremost. That’s what people love from a movie, when they feel something viscerally, and suspense, horror and comedy are the biggest things you can make an audience feel. All great horror movies have comedy at some level, Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) is one of the funniest films I can remember, The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) is an extremely funny film… so is The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1974) – it’s full of jokes!

I think there is a wonderful compliance between horror and suspense and fear, it’s really the most entertaining thing you can give an audience. That’s why people love them and don’t tire of them. I think genre labels can be reductive, like for most people there is nothing more repulsive than that awful label “elevated horror,” as if it’s somehow better for you. It’s like saying “somebody won’t like this”—if a movie is scary, people will love it! One of the most frightening movies I’ve ever seen in my whole life is Sátántangó (1994) by Béla Tarr: all seven hours and 45 minutes of it. You probably have to accept that’s probably an “art movie.”

IS – I always say one of the most terrifying films ever made is 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968).

BR – It’s very frightening, no question! there are more obvious ones, like Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968) and all that. Horror movies have always been the province of the very best filmmakers, it’s weird that somehow when people say just “horror,” people’s immediate response is it’s something very exploitative and cheap. Of course there are cheap, exploitative horror films, but that doesn’t mean in its essence it’s cheap and exploitative.

IS – Is there a film that got away from you, one that you were desperate to make but it never happened?

BR – Not really. There are some things I’m planning to make and haven’t given up on, so I don’t think those really count.

IS – Any new films you have been impressed with? (Note: the 2020 Oscar nominations were announced the day of the interview).

BR – It’s always controversial when they put out the Oscar nominations, but this year seems a better bunch of films than I’ve seen in some years. Some years, without naming names, you kind of go WHAT? ARE YOU KIDDING?

There are some films I would’ve liked to have seen in there that weren’t nominated, but that’s always the case. A lot of them seem pretty interesting: kudos to the people who got the nominations. A couple of them I like very much. I liked Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino, 2019; pictured below), I thought that was a really terrific movie. I liked Parasite, and that’s already two really good movies, and sometimes there’s not even one! I don’t think there was any real stinker this year.

Another film I liked was Honey Boy (Alma Har’el, 2019), I thought that was really good, and it’s a shame it didn’t get anything. And it was different, too. I liked the Adam Sandler film Uncut Gems (Safdie Brothers, 2019), the gambling thing is a little similar to Bad Lieutenant (Abel Ferrara, 1993), but it’s also Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler. Bad Lieutenant was such a classic, I think I just like anything with Harvey Keitel in it. That’s my only criticism of The Irishman (Martin Scorsese, 2019), I wanted Harvey Keitel in it more. Every film should have Harvey Keitel in it, really, shouldn’t it? I want to see Eyes Wide Shut (Stanley Kubrick, 1998) recut with Harvey Keitel in it!

IS – I think that footage has been destroyed, sadly.

BR – I actually don’t think they actually shot anything, but it would still be great.

IS – So obviously, with Scorsese and The Irishman, I have to ask you: are Marvel films cinema?

BR – The obviously answer is: “of course they are!” I think there are two real issues here. One is positive, and one is problematic. It is fantastic that theatrical movies can take over a billion dollars in less than a month: it’s still such a mainstream, vital business that can happen, and that’s really significant, given all the technology and all the things distracting young people today—it wouldn’t necessarily be the case. It’s fantastic that power is still there, and the vitality of feature film is still so important to the culture.

The flipside of that here in the UK and the in the US, still very healthy in just pure total numbers, is that all of the money is being sucked up by the giant tentpoles that are coming out of Disney, so there isn’t money left for anybody else, and others are struggling for the awards season’s pennies on the floor. I would say the third aspect of it is that it was purely expected to make its money back theatrically: is The Irishman really economical at 165 million dollars? The answer is probably no.

IS – But with Netflix, they pay all the directors and actors upfront, and they get nothing in the back end.

BR – You never get anything in the back end anyway! Anybody who is making films at that level is extremely lucky and privileged, and it’s not a right for anybody, it’s definitely a privilege working and doing the stuff. I certainly feel really privileged that I’m still working, still doing stuff that’s interesting and sometimes has a little bit of scale to it. Nobody has given me 150 million dollars to make a film, but you know, that’s OK, you don’t need that much money… That’s an awful lot of money.

IS – I think the big issue is distribution.

BR – It’s a big issue, and one of the things everybody forgets is that everything is much more available now. Inasmuch as if you want to watch all the classic arthouse films, you can go on the Criterion channel and just see them all—that wasn’t true before, not even slightly. I love that certainly in Los Angeles there are still some fantastic repertory houses, like the American Cinematheque, the Egyptian Theater and Tarantino’s theatre, The New Beverly. These places show really interesting, unusual programming. And here you have some really good repertory places, like the BFI. People want the big screen and communal experience, and they want the feature films. There is so much stuff you can’t watch it all, and half of the time I want to catch up with stuff from the 1930s that I haven’t seen. The other thing that always strikes me is that people forget that sound movies have only been around since 1927, so 93 years, it’s not very long. Everything going on now is still basically early cinema, in historical terms.

IS – Do you think there will be some kind of new technological event that will change how films are made, like with DV?

BR – Probably there will be things that will change, but there is something about the way a movie works and the way we watch that does seem to fit with the kind of alpha rhythms or brainwaves of dreaming and the imagination in such a kind of conjugate and powerful way that I don’t think people will ever tire of it. All films have secret content that is only apparent years later, and a film like Ivans XTC is a perfect example of that. If you look at the film now, it’s not just a story, it’s a perfect little time capsule of 1999. When films have that, it’s one of the most powerful things, the way that they are time capsules.

IS – I have one final question from my friend Dan Waters, who wrote Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1979) and Batman Returns (Tim Burton, 1992): is there any way one can see the HBO Inside Out short with Djimon Hounsou that you did?

BR – You know what? “I don’t know” is the honest truth. As far as I know, they are available on video, but I may be wrong.

IS – He says it was the one he couldn’t find.

BR – Then unfortunately I don’t think I can help, I don’t think I have any copies.

…

If you enjoy this interview, you may want to check out his Trailers From Hell segments, where he specialises in Ken Russell films but has also done some on If… and Sorcerer.