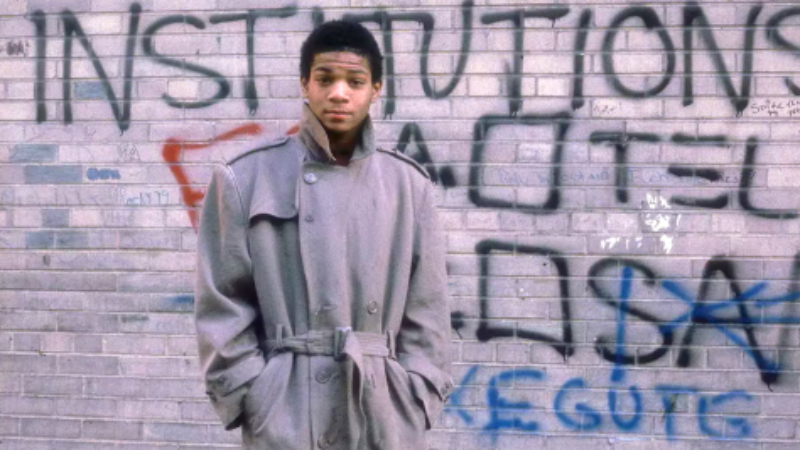

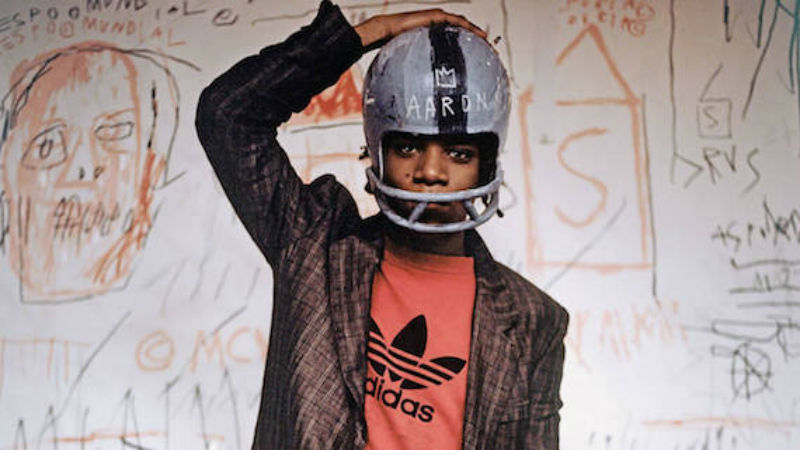

This is the type of movie that does exactly what it says on the tin. The highly descriptive 11-word title could as well function as a mini-synopsis of the film. This is a documentary about Jean-Michel Basquiat around the years of 1978 and 1979, when he was just 18 and 19 years of age, mostly unknown. His talent was beginning to flourish and he was sensing that he was about to become a “very famous artist”. Basquiat was a teenager with great ambitions, ideas of grandiosity, a lot of talent and a very dirty mind. This is a film about an artist in the making.

It starts off with images of the derelict and filthy streets of New York during said years, all teeming with poverty, drug addicts and graffiti. This is pre-Giuliani, and there are no signs of gentrification, instead the metropolis looks hellish and post-apocalyptic. This is where the young Black artist began painting and scribbling. His childlike drawings and blocks filled with written words – almost invariably in public places – may look banal and immature to the least attentive, but in reality his work was anything but puerile. He coined the term Samo (short for “same old shit”), which became a widely used graffiti tag. But there was nothing old and unoriginal about such work. The acute political messages, the anti-racism statements, plus the commentary on colonialism and class struggle are all in there. The writing’s on wall.

The central pillar of this doc are talking heads interviews celebrating, sharing anecdotes and reminiscing about a very audacious artist who died at the age of just 27 to an overdose of heroin (the same age as Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimmi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse, all equally dirty). This is an intimate and romanticised portrait of Basquiat, as perceived by friends who liked and admired him enormously. Interviewees include Jim Jarsmuch (who refused to take part in the 1996 biopic Basquiat, directed by Julian Schnabel), costumer designer Patricia Field, Puerto Rican artist Lee Quinones, plus some of his close and less famous friends, lovers and associates. The artist himself is rarely heard. This third-person approach provides the late Basquiat with some sort of unearthly and uncanny quality.

On the downside, this is also a very esoteric film, and it’s unlikely to convert any new fans and admirers. A very conventional doc about a very unconventional artist. Not a colourful and pulsating piece of work, mirroring the pieces created by the flamboyant artist. It’s an effective and concise film product that does what it says on the label, without adding any new flavours and twists.

Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat is out in selected cinemas across the UK on Friday, June 22nd. It’s out on VoD on Monday, November 26th.