Throughout his directorial films, American filmmaker, actor, and visual artist Dennis Hopper used music, songs, and sound to convey several important factors. Using lyrical insinuations, Hopper provided indications to the audience of the emotional headspace that his characters inhabited. He also used music to signpost the era in which the narratives took place and to construct the political and societal conditions of the times and how these impacted upon the lives of his protagonists. While all this sounds serious and deeply considered on Hopper’s part, he also knew that a good song matched with some iconic cinematography could propel his films beyond the cinema screen and into the popular culture.

Hopper’s directorial debut film Easy Rider (1969) is an obvious contender for how Hopper used music to complement the visuals. It was one of the first films to pull popular songs by already established bands and artists and place them on to the soundtrack. Among other components that made Easy Rider a hit with critics and audiences, the use of music was the most compelling and influential to other filmmakers of the time who could use popular songs to create instantaneous emotional connections for the audience to savor.

Hopper’s use of music and sound on his second feature The Last Movie (1971), was a continuation of Easy Rider’s folk rock style yet included elements of sound collage, indigenous music and chant, with an abrupt and destabilising fast cut editing technique that meant the music never lingered for long. Out of the Blue (1980), Hopper’s third film, used punk rock music, Elvis Presley songs, and Neil Young’s folky compositions, to portray the generational war, family dysfunction, sexual abuse, and addiction that takes place within the film. Hopper’s fourth film, Colors (1988) came loaded with hip-hop and rap standards that soundtracked the life and urban environment of the predominantly Black and Latino gang members who ran the streets of Los Angeles. The soundtrack brought hip-hop and rap to a much wider audience through its use within the film. The neo-noir film, The Hot Spot (1990), saw Hopper commission a hybrid of blues and jazz music by Miles Davis and John Lee Hooker. It was a steamy, simmering composition that befitted the tale of obsession, lust, and betrayal set within the putrid Texan heat.

To demonstrate the importance of music in Hopper’s films, I’ve selected 10 essential tracks from Hopper’s soundtracks that in some way define the films, the eras, and the surrounding cultural landscapes that the narratives revolve around. It is in no way definitive, but it’s a great sampler of how music played an inventive, and meaningful role within his films. Let’s begin.

…

.

1. Steppenwolf – Born to Be Wild, from Easy Rider:

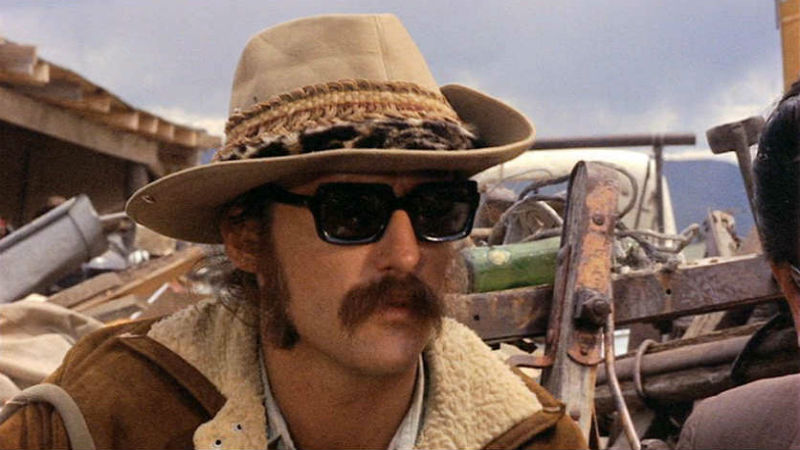

If one song has become synonymous with Easy Rider’s hell-for-leather iconography it is Canadian American rock band Steppenwolf’s 1968 anthem Born to Be Wild. Though not the first song to be heard on the soundtrack (that goes to another Steppenwolf song The Pusher) it lays down perfectly the freewheeling’ attitude of the first half of the film in which two hippie bikers, Billy and Wyatt (Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda respectively), set off across the southern states on their custom-built motorcycles. Financially secure after selling cocaine over the Mexican border, they embark on an odyssey that sees them cruise through the sunlit vistas, wind in their (long) hair, and freedom on their side.

Born to Be Wild is an anthem that points towards a collective freedom and embracing the road in a state of love, understanding, and togetherness. However, while the progressive movements of the 1960s certainly promoted these collective values, Billy and Wyatt have dropped out of society completely and are headed out alone. Instead, their version of the American Dream is to get rich quick, ride off to New Orleans to attend the Mardi Gras festival, get loaded on drugs, and then “retire to Florida”. As many of their peers would eventually do, Billy and Wyatt have exited the idealism of the 1960s and instead embraced “individual freedom” over the collective wellbeing of American society.

.

2. It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) – Bob Dylan, from Easy Rider:

On the road, Billy and Wyatt are joined by a normie Southern lawyer named George Hanson (Jack Nicholson) who tags along to New Orleans to visit a bordello he’s heard about. George’s betrayal for hanging out with the “longhairs” is punished by a gang of Southern thugs who beat him to death while he sleeps. It is at this point where Billy and Wyatt’s dream begins to shatter. Bob Dylan’s nightmarish 1965 song “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” arrives after the two bikers’ trip-out on acid in a New Orleans cemetery. It is the comedown song to end all.

Dylan’s lyrics reflect the death of the utopian dream of 1960s’ idealism, and that corporate power, materialism, war, and injustice would always overpower the alternative way of life proposed by the radical and progressive movements. Billy and Wyatt continue their journey, though Wyatt confesses that they “blew it”. They die when a passing hick waves his gun at them and it accidentally goes off. And so, dies with them the so-called American Dream.

.

3. Me and Bobby McGee – Kris Kristofferson, from The Last Movie:

Unlike the soundtrack style of Easy Rider, in which Hopper placed popular studio recorded compositions over the top of his imagery, The Last Movie uses songs recorded live within the film itself. The recordings are rough, laced with microphone hiss and the sound of wind whipping in and out. Me and Bobby McGee by a then little-known folk singer called Kris Kristofferson is first heard as Hopper’s cowboy stuntman character Kansas rides past Kristofferson and singer Michelle Phillips harmonising the song on the side of a Peruvian mountain. The song would become more famous as covered by Janis Joplin for her 1971 album Pearl and topped the US music charts when it was released posthumously.

The lyrical refrain of “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose” reflected the post-1960s disillusion that the progressive movements hadn’t turned into more permanent societal change.

.

4. The Party Walk – various artists, from The Last Movie:

Alongside the live recorded folk renditions, the soundtrack to The Last Movie contains a chaotic and overwhelming mosaic of music and sound. Hopper took the overlapping aural assault of the New Orleans acid trip scene in Easy Rider and stretched it out over the entire film to create an enveloping, immersive, and disorientating experience. This merging of sound and music is best demonstrated by a scene within the film in which Kansas moves through a house party where every room is overtaken with a different form of music. This includes a harmonised folk song, a group of stoned partiers chanting, a clunking out of tune piano and a rabble of dancers. All the sounds overlap and blend with the voices of the party until the whole varying musical styles come crashing overtop of one another. Kansas breaks down in tears, overwhelmed by the noise and stimulation. This sound collage style continues throughout the film.

.

5. My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue) – Neil Young, from Out of the Blue:

Hopper’s third directorial cut was the Canadian film Out of the Blue. Originally only cast in a small supporting role, Hopper took over the production when the original director and screenwriter left. Hopper rewrote the script, recast some roles, and injected the film with a nihilistic punk rock energy. The original theme focused on a young girl named Cindy (Linda Manz) who is saved and rehabilitated by the welfare state. In Hopper’s new take, Cindy – now named Cebe – falls prey to her parents physical and emotional abuse. She kills them and herself in a violent act of retribution. Neil Young’s acoustic 1978 song My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue) concerned the generational shift that was taking place in the late 1970s as the hippies’ dominance (Young and Hopper included) within popular culture withdrew to the sidelines and was replaced by the punks as the new countercultural force. It reflected the mood within the film with Cebe standing in for her generation’s dissatisfaction with the hippies’ inability to practice what they once preached and enact the changes to society they once talked about. Hopper holds the gun to his own head and the head of his own generation’s inadequacy.

.

6. Out of Luck – Pointed Sticks, from Out of the Blue:

After seeing her mom shoot-up heroin with one of her dad’s deadbeat friends, Cebe runs away to the city. Her adventures lead her to a small, sweaty club where Vancouver-based punk band the Pointed Sticks are performing a kinetic live set. Out of the Blue fizzles with a punk rock attitude yet features very little music from the actual genre. Here, though, we are treated to two Pointed Sticks songs back-to-back. A live rendition of Somebody’s Mom and a recorded and mimed performance of Out of Luck.

In a film that offers very little hope for the outcome of the characters, this moment gives Cebe, and the audience a short reprieve from the darkness. Cebe is invited on-stage to hit the drum skins along with the band. For a moment another future is presented to Cebe in which her aspirations to become a punk rock star is fulfilled. It doesn’t last long, and the bright and brash stab of punk music is once again buried by Young’s brooding and deathly My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue).

.

7. A Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste – Mc Shan, from Colors:

Hopper’s fourth directorial film Colors came after a period of exile from Hollywood. Reeling from the critical and commercial fallout of The Last Movie, and Out of the Blue, plus the copious amounts of drugs and booze he ingested during the period, his work suffered greatly, and the acting gigs he was offered were mostly abroad. However, after getting clean and sober, and a triumphant come back with three stellar performances in Blue Velvet (David Lynch), River’s Edge (Tim Hunter), and Hoosiers (David Anspaug),all from 1986, he was handed another shot at directing for a major studio picture. Hopper used the story of two white cops patrolling the gang-ridden streets of Los Angeles as a gateway to explore the lives of the gang members and the system that allows predominantly Black youths to turn towards gang membership as a replacement for fractured family values and broken social structures.

The soundtrack to Colors was a compilation of contemporary hip-hop and rap music. Though within the film itself the music is buried and mostly heard in passing as gang members blast the songs from car stereos and ghetto blasters, the music is central to the characters life. MC Shan’s “A Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Waste” details via awesome rhymes the reasoning behind why gangs exist in the first place and displays the negative aspects of being in a gang where “there is no turning back” and where life becomes about “fightin and killin”.

.

8 – Go On Girl Roxanne Shante, from Colors:

Across his soundtracks, Hopper would embrace different genres of music to compliment his narratives. Using folk, rock, psychedelic, jazz, punk, and hip-hop to great effect. It’s telling though that most of his films center on male protagonists and therefore the principal voice of his soundtracks was also predominantly male. Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Kris Kristofferson, Neil Young, Ice-T, Elvis Presley, and Miles Davis give voice to these male-centred perspectives. On the Colors soundtrack, Hopper features songs by two prominent female hip-hop artists. Let the Rhythm Run by the all-female group Salt-N-Pepa and Go On Girl by the female MC Roxanne Shanté. While the narrative of Colors, much like the rest of Hopper’s directorial output, sidelines female characters to roles as love interests, sex workers, or drug addicts, it’s worth noting that the female rappers featured on the soundtrack are nothing of the kind. Within the male dominated arena of hip-hop and rap music both these artists trailblazed the way for a shared space within the future of mainstream hip-hop, rap, and soul music that was to come.

.

9. Coming to Town – Miles Davis, John Lee Hooker, Tim Lee Drummond, Earl Palmer and RoyRogers, from The Hot Spot:

The final trifecta of Dennis Hopper’s directorial career jettisoned the cultural and political elements of his previous four films and replaced it with narratives that concerned male and female relationships. Catchfire (1990) was about a hitman falling in love with the girl he’s sent to kill. The Hot Spot sees drifter Harry Madox (Don Johnson) succumb to the charms of two female characters. Hopper’s last film Chasers (1994) saw two military officers tasked with escorting a beautiful female officer accused of deserting her unit to military jail. The female lead just happens to be played by Playboy Playmate Erika Eleniak. The most interesting entry in Hopper’s final three films is The Hot Spot.

While the film was certainly adequate in acting and direction, and was his most flashy and star-studded film, the soundtrack is what it is really noted for. Hopper commissioned jazz maestro Miles Davis and blues guitarist John Lee Hooker, as well as an ensemble of esteemed musicians to compose an original score. The laidback guitar and deep vocal hums of Hooker encircle Davis’s lazy horn and together they both maintain a steady and competent groove. Coming to Town is a prime example of how the music simmers and floats around the film’s action.

.

10. Bank Robbery – Miles David, John Lee Hooker, Tim Lee Drummond, Earl Palmer and Roy Rogers, from The Hot Spot:

Unlike his previous films, The Hot Spot’s composed instrumental score doesn’t give the audience a hint as to the inner workings of the characters minds. Instead, the score sits barely noticeable within the film. However, during a scene in which Madox sneakily robs a bank while the tellers are putting out an apartment fire across the street, the music becomes a focal point as the scene plays out and a tense moment in which Madox comes face to face with a blind bank patron. The music suddenly goes quiet and only the deep hums of Hooker’s voice can be heard as Madox’s moves slowly away. As he slips by and escapes without notice, the full band suddenly kick in once again. It’s perhaps the only example within the film where the music involves itself within the narrative. As a standalone record, the soundtrack is a simmering, sultry affair and without question a musicologist’s wet dream. As a soundtrack to a Dennis Hopper film, with those all-important signposts, and lyrical insinuations absent, it falls flat somewhat.