We are delight to announce that the fourth edition of the ArteKino Festival will take place throughout the month of December, from the very first day of the month until the end of the year. This gives you plenty of time to enjoy the 10 films carefully selected exclusively for you!

The online Festival is aimed at cinephiles from all over Europe who are seeking original, innovative and thought-provoking European productions. You can watch films on ArteKino’s dedicated website and also on ArteKino iOS and Android app (developed in conjunction with Festival Scope). Subtitles are available in ten different languages: English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish and Ukrainian.

Once you have finished watching your favourite movies, you can rate them on a scale 1 to 5. The film with the highest score will receive the European Audience Award of €20,000. The sum will be shared between the director, the producer and the international distributor, thereby encouraging a wider geographical distribution of the film. In addition, a jury of six to 10 young Europeans, aged between 18 and 25, will select a movie to win an award of €10,000. The young Europeans will be invited to Paris for the European Audience Award and the Young Public Award Ceremony in January.

ArteKino is supported of the Creative Europe Media Programme of the European Union. Below is a list of the 2019 selection, listed alphabetically. Click on the film title in order to accede to our exclusive review (where available) in here in order to accede to the ArteKino portal and watch your favourite European movies right now!

PS – The winner of this year’s ArteKino has now been announced: Psychobitch. You can watch it for free until the end of January by clicking here.

…

.

1. Messi and Maud (Marleen Jonkman):

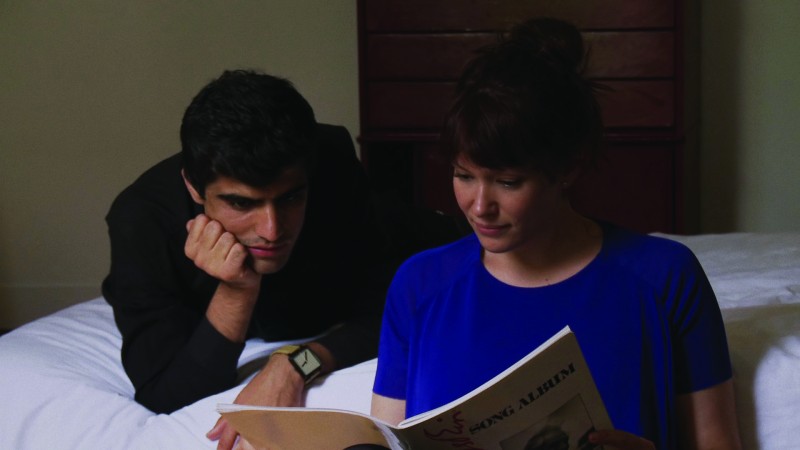

They say that children are the gifts that keep on giving, yet for many couples out there, their Christmases, birthdays and anniversaries seem empty of gifts. So it is for Frank (Guido Pollemans) and Maud (Rifka Lodeizen), both now past 40, eager to put a decade of miscarriages and false starts behind them. Flying to the Andes, an awaited rebirth is marred by another miscarriage, the following argument causes Maud to abandon her husband for the barren countryside. Only through a chance encounter with 8-year-old Messi (Cristobol Farias), does Maud re-discover the value of life.

Lodeizen delivers an extraordinarily well put together performance, even if the story sounds very conventional. Twelve minutes into the film and Lodeizen clothes herself in funereal black robes, wailing at the failures her blond body holds. She holds the contrived moments with an elegiac loneliness, aching for a child of her own to carry and hold. Her travel companion is the very thing she’ll never bear, a sprightly child, fervent, feverish and full of life.

Messi and Maud is also pictured at the top of this article.

.

An unsettling visual journey through gender norms in contemporary society. Immersed in a kaleidoscopic mosaic of visually powerful scenes, viewers experience the ritualised performance of femininity and masculinity hidden in ordinary interactions, from birth to adulthood.

Isolating the slightly grotesque, uncanny elements surrounding our everyday life, NORMAL meditates on what remains imperceptible about it – its governing norms, its inner mechanisms. The result is that what counts as ‘normal’ does not feel so reassuring, anymore.

.

Fifteen-year-old Frida assumes to be the class outsider. In this world of the “Generation Perfect”, the other kids at school agree: Frida is so weird. Marius does pretty much everything he can to be exemplary. When the two are paired up as study buddies, he sees it as another opportunity to show everyone what a great guy he is. But Frida has no intention of being “fixed” by the class golden boy.

Their study sessions become the catalyst for a turbulent relationship. Yet in his fights with Frida, Marius also experiences something exciting, challenging and completely new.

.

4. Ruth (Antonio Pinhao Botelho):

Ruth is about football, but, apart from a brief sequence at the end, there are no scenes of the great game being played. Instead, this movie uses sport as a means to explore Portugal’s colonial legacy, delivering a tale of a changing nation.

The year is 1958, the country is Portuguese Mozambique and the city is Lourenço Marques (now called Maputo), introduced in an opening montage as the “Jewel of the Indian Ocean”. Our protagonist Eusébio (Igor Regalla) is a young black lad from the streets, impressing everyone he meets with his devastating footballing skills. Playing for Sporting de Lourenço Marques, he is noticed by white Portuguese scouts for Benfica, who regularly travel to Mozambique to find players who can play for clubs back home.

.

The artist must look in many places in order to find their muse. For Fonnard, capturing the untamed spirit of the wandering refugee brought wasn’t a mere altruistic gesture. Captured under the slanted camera angles, Fonnard cuts vegetables with Ahmad, sharing a community of comradeship and love. Exchanging lyrics of a poetic and musical nature, the intertwined art forms form the basis for a concert that might prove Fonnard’s purest work. With Ahmad at her side, Fonnard has a new muse, a new mirror and, most importantly, a dear friend.

This is one of the more compelling documentaries of the year, detailing the companionship that close quarters can both bring and inhibit. For a generation of viewers versed in Big Brother and I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here, this might not come across as something entirely original, but Narboni’s piece feels genuinely organic, instead of tediously automated.

.

6. Selfie (Agostino Ferrente):

Alessandro and Pietro are 16 years-old and live in Naples, district of Traiano where, in the summer of 2014, Davide Bifolco, also 16, was shot by a policeman who mistook him for a fugitive. They are inseparable friends, Alessandro works as a waiter in a bar, Pietro dreams to become a hairdresser. Alessandro and Pietro accept the director’s proposal to shoot themselves with an iPhone, commenting live on their own daily experiences, their close friendship, their neighbourhood – now empty, in the middle of summer – and the tragedy that ended Davide’s life.

.

7. Sons of Denmark (Ulaa Salim):

Shakespeare famously proclaims in Hamlet: “There is something rotten in the state of Denmark”. In Sons of Denmark something is indeed very rotten in the Scandinavian country. Forget nice social democrat Denmark, the land of hygge, Danish pastries and the Little Mermaid. This is a country where migrants live in fear of vicious, xenophobic gangs, where pigs’ heads are deposited where Muslims gather, and random acid attacks are made on innocent foreigners. This film is an impressive debut by its director and writer Ulaa Salim. Made by the migrant community in Denmark, mainly Syrian and Iraqi, and their sympathisers, it portrays a country of cruel disdain for those who seem just a bit different.

.

8. Stitches (Miroslav Terzic):

Based on true events, Stitches takes place in contemporary Belgrade, 18 years after a young seamstress was coldly informed of her newborn’s sudden death. She still believes the infant was stolen from her. Dismissed by others as paranoid and with a mother’s determination she summons the strength for one last battle against the police, the hospital bureaucracy and even her own family to uncover the truth.

9. Thirst (Svetla Tsotsorkova):

A couple and their teenage son live on a hilltop, doing the laundry for local hotels, despite the intermittent water supply. Their simple life is overturned by the arrival of a father-and-daughter team of diviner and well-digger, who promise to bring an end to this precarious existence by finding a source on their arid hill. But ultimately, these newcomers quench a thirst that is much stronger than that for mere water.

.

This somewhat millennial take on the midlife crisis follows a bunch of friends in a hip Berlin neighbourhood for 24 hours while they celebrate – or at least attempt – the birthday of one of them. The German drama, which premiered in Rotterdam earlier this year and is available online throughout December as part of the ArteKino Festival, is a snapshot of the existential ennui of the 30-somethings.

The writer Övünç (Övünç Güvenisik) turns 30 and calls upon his mates to party, all the while coping with a severe creative block. His friend Pascal (Pascal Houdus) is coming to terms with a bad breakup with Raha (Raha Emami Khansari), a struggling actress with bouts of depression. Other members of the group – such as Henner (Henner Borchers) and Kara (Kara Schröder) – also deal with insecurities. Together, they venture outside in order to enjoy life, although internally, they have no clue how to begin.