The Eternal City is often portrayed as joyous place, filled with life, excitement, beautiful people and incredible scenery. But when walking very late at night, it can often feel rather malevolent and mysterious, filled with long-hidden secrets. The Rome of Zeros and Ones is a pandemic-infused noir suffused with dark shadows, the endless symbols of Christianity repurposed for much darker purposes.

Into this reality comes American military officer JJ (Ethan Hawke): equipped with a face-mask, he looks like he has never smiled in his life. He is on a mission to seemingly save the world from an unknown threat. He invokes Jesus through voiceover more than once, boldly stating that he was “just another soldier.”

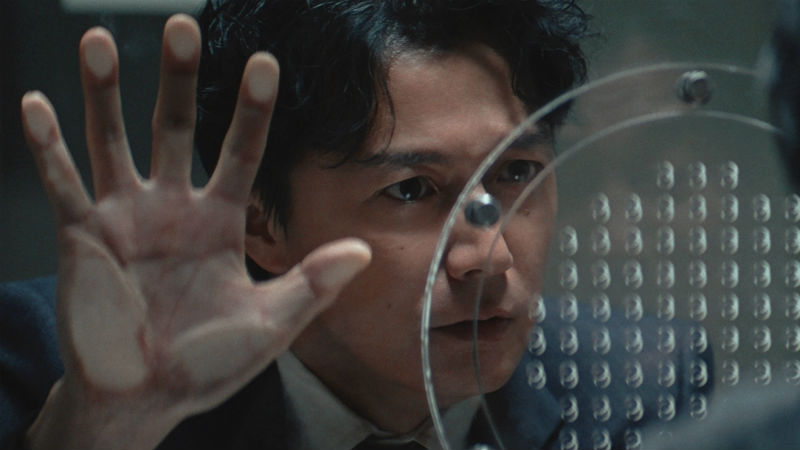

Any of the genuine Christian elements such as loving your neighbor, turning the other cheek and self-sacrifice seem omitted here: this is a cold and lonely world, exacerbated by the worst pandemic in a hundred years. It’s difficult to say exactly what he is fighting, only that he manoeuvres an almost empty world, solely populated by Russian spies, Asian drug dealers and American spooks. His brother (also played by Ethan Hawke) has been detained, accused of promoting revolutionary ideals across the country. What those ideas are, we never quite know, as the film prefers to shroud its central mystery in an ambivalent, shadow-heavy tone.

Ferrara works hand-in-hand with cinematographer Sean Price Williams, one of the best cameramen in the business, as evidenced through his work with the Safdies and Alex Ross Perry. Williams shoots Rome almost entirely at night, making it seem as filled with betrayals and secrets as The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949). This is complemented by grainy, over-exposed digital footage, ramping up the paranoia with a sense of constant surveillance. The music by Joe Delia then expands the scope where the evidently small budget can’t, featuring reverb-heavy military drums and Glenn Branca-like guitars. The result is an incredibly moody spy thriller so baked in cynicism that it makes John Le Carre look like Frederick Forsyth.

The setting make absolute sense and is integral to the film’s mood. Italy was the ground zero for coronavirus in Europe, the haunting images emerging from the country a terrifying prelude to what would soon devour the continent. Nonetheless, while it is definitely a more interesting corona-influenced film than the comedies and dramas I have seen so far, finding a way to wrap it into a political thriller, Zeros and Ones preference for atmosphere over coherence can make it hard to find a grip.

Ferrera is a great experimental filmmaker, making his relative misfires still worth exploring and digging into. But while something such as Siberia (2019) could work brilliantly as an exploration of the mind and soul despite having little to no plot, Zeros and Ones’ attempt at reconfiguring a genre usually obsessed with plot makes it harder to love. No one could come out of that film knowing what actually happened, but certain images — like the saints of the Vatican shot like members of a secret cult, or Ethan Hawke running down a deserted, barely-illuminated alleyway or yet another Ferrara sex scene between JJ and a mysterious woman — will stick with me, creating an allegory for a world that has been plunged into a new dark age.

Zeros and Ones played in Concorso internazionale at Locarno Film Festival, when this piece was originally written. On all major VoD platforms on Monday, March 21st (2022).