The nuclear family. Dad Osamu (Lily Franky) takes son Shota (Jyo Kairi) to a local convenience store where, through a series of long rehearsed routines, they steal a series of items. Just another day of getting by.

Mum Nobuyo (Ando Sakura), a former sex worker, dispenses advice to her younger sister Aki (Mayu Matsuoka) – who gets fired from a club where girls display themselves in various states of dress and undress to clients through one way mirrors. Basically, she’s been caught sticking her hands in the till. Grandma (Kirin Kiki) lives with the family making a total of five persons in one small living space.

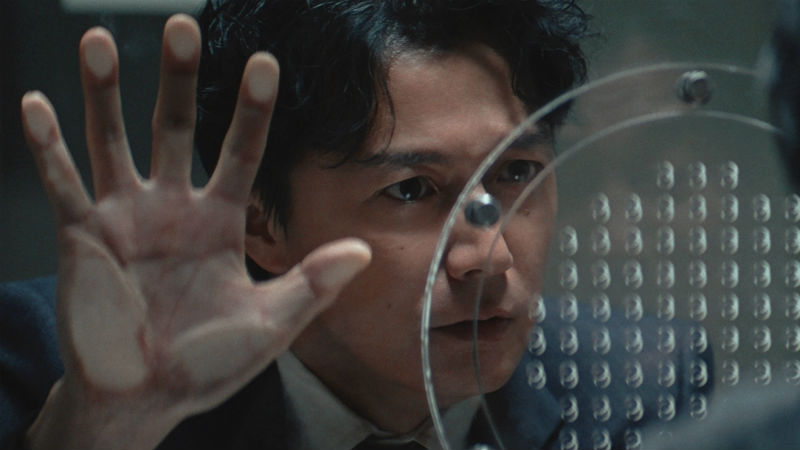

Dad explains to Shota that he and his partner are bonded here (puts hand on heart) not here (puts hand on genitalia). Yet one afternoon when everyone else is out, she comes on strong and the two adults indulge in an afternoon of passion. Until the children come home unexpectedly.

As if all these familial relationships weren’t complicated enough, father and son spot a little girl (Miyu Sasaki) sitting on the street. She’s hungry, so they take her to their home and give her a meal. That turns into an overnight stay. They try and take her back to her own home, but it’s clear in the street outside from her parents’ clearly audible and highly vocal arguing that neither father nor mother wants the child currently nor ever did. So the family decides to take Yuri in as its newest member.

Shota takes Yuri on a shoplifting trip but it doesn’t go so well. She’s both naive and inexperienced. A shop assistant tells him to quit involving his sister in his shoplifting activities. Much later on, the boy takes the girl on another shoplifting spree which ends in him getting caught, the police questioning the entire family and unexpected revelations about the family itself.

Koreeda has ventured into this territory of the non-nuclear family before. Nobody Knows (2004) featured a group of children left to fend for themselves in an urban environment. Like Father, Like Son (2013) had each of two couples mistakenly bring up a boy as their own after two boys were switched at birth in the hospital. The Japanese director seems fascinated by family function and dysfunction. Why the family unit matters – and when it might be redundant.

All of which is constantly engaging and its assorted characters compelling. One is drawn to them and yet, at the same time, it’s not a family you’d want to be part of when its reality is eventually exposed. The film picked up the Palme d’Or in Cannes and numerous other awards elsewhere. Koreeda seems to be on a winning streak at the moment after The Third Murder (2017). For good measure, Shoplifters also boasts a terrific score by Haruomi Hosono, his first for Koreeda.

Shoplifters plays in the London East Asia Film Festival (LEAFF) on Sunday, November 4th . Buy tickets here. It’s out in cinemas Friday, November 23rd, and on VoD on Monday, March 25th (2019).