With a career spanning nearly four decades, the 62-year-old Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa has directed more than 40 films, and he has navigated a wide variety of genres, ranging from horror and suspense to romance and family drama. He directed four films in the past two years alone. The filmmaker, who is not related in any way to Akira Kurosawa, is also a film writer, critic and professor.

Kurosawa has recently stepped on European cinema soil where he directed the French ghost story Daguerrotype. This classy art house feature tells the story of a contemporary photographer who employs 19th century daguerreotype plate techniques involving lengthy exposures. Subjects must remain utterly motionless for 20 minutes at a time in order for their image to be captured without becoming blurred. And that might give uninvited entities the opportunity to manifest themselves! Daguerrotype is part of the Walk This Way Collection, which DMovies is promoting in a partnership with The Film Agency and Under The Milky Way. You can watch it at home right now on all major VoD platforms!

In our short existence of less than two years (we celebrate our second birthday in a few weeks, on February 6th), Kurosawa has flown under our radar three times, firstly with Creepy, in 2016, and twice last year, with Daguerrotype and Before We Vanish. So we decided to ask him a few questions about his experience in Europe, his connection if any to Western filmmakers such as Spielberg and Hitchcock, what genres he wants to work on next and whether he can predict the future!

.

Jeremy Clarke – How would you describe your experience working with a French cast and crew in Daguerrotype (2017; pictured above)? Was it a good experience? Would you like to work with foreign casts and crews again in the future?

Kiyoshi Kurosawa – It was an amazing experience. Against my perceptions the attitudes of the French cast and crew were very similar to those in Japan. All of them understood their job was “to realise the director’s vision with all their abilities and efforts”. I really appreciated it.

JC – Could you please explain the writing process of Daguerrotype? I see two other names besides you in the screenwriter credit.

KK – Based on an idea of a story which I had been working on over 10 years, I wrote a script set in modern France. The script was translated into French, and then the brilliant French screenwriters rewrote it, so that the script would fit well into the situation in today’s France. So it was a complicated process.

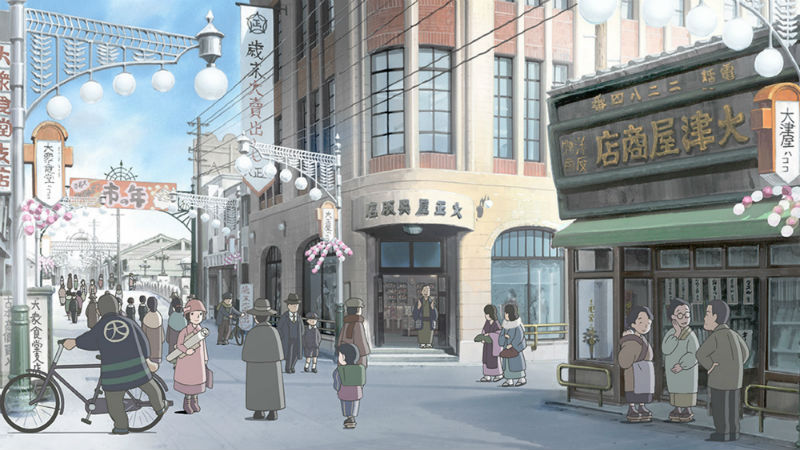

JC – You seem to be a director who enjoys working on a vague idea or theme, and then shapes the movie during the production process bringing in various images, effects, scenes and sequences. Pulse (2001) or Before We Vanish (2017, pictured below) would be examples for this. In which way does this approach specifically appeal to you?

KK – The very base of cinematic expression is to film the reality in front of you using cameras. So, the similarity with the reality would be the feature of a movie. This could be also its limitation, but anyway, I am particularly interested in the fact that a movie is almost the same as reality, but at the same time is slightly different than reality. This difference or unreality is always my starting point when I create my work.

JC – Could you please explain the reason why a low altitude plane comes often at a climax of your works, such as in Pulse or Before We Vanish?

KK – That’s an interesting observation. I never realised it myself! It might be because a movement of a protagonist looking at the sky seems to me very cinematic somehow. However, I can’t explain it that well.

JC – In Before We Vanish, I see influences of Spielberg’s E.T. the Extraterrestrial (1982). Do you appreciate the movie?

KK – Spielberg is one of my favorite filmmakers and I also appreciate E.T.. However, I don’t necessarily consider it as the best work in his filmography. There’s no particular borrowed motif in Before we Vanish. However he has created many human-alien encounter SF movies and my favorites would be Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and War of the Worlds (2005). So it’s possible that there are Spielberg influences at some unconscious level.

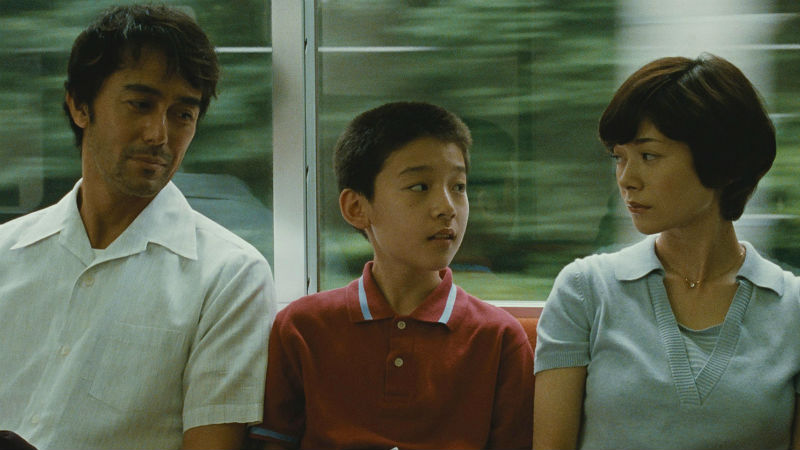

JC – Creepy (2016, pictured below) recalls works by Hitchcock (especially Vertigo and Psycho; 1958 and 1960 respectively) as well as Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999). To what degree were you aware of these films when you filmed Creepy?

KK – Sorry, but I was aware of neither Hitchcock nor Miike.

JC – You have been working in various genres. For crime, Creepy and Cure (1997). For drama, Tokyo Sonata (2008) and Before We Vanish. For romance, Tokyo Sonata, Journey to the Shore (2015) and Before We Vanish. What genre or genres would you like to revisit on future movie projects?

KK – In the future I want to work on genres I haven’t worked on yet. I haven’t worked on genres such as musical, historical and comedy movies.

JC – When you join a project (as a screenwriter or director), what makes you do so? How do you know if a story makes you want to tell it?

KK – That’s a difficult question. I cannot name a core element which makes a movie. It also means that there are too many factors. One thing I can say would be meeting people. It might be a producer, an actor or an original writer. Meeting someone, in the end, boosts the production of a movie, I guess.

JC – Looking back at Pulse, that movie catches the historical moment in which people used dial-up internet connections and the internet itself was still new for most of us. In today’s cultural development phase is there anything particular which inspires you?

KK – This question is also hard to answer. When I’m told that Pulse predicted the future, I have to say that was not my original intention at all. How a movie is interpreted by society after its birth is purely accidental.

JC – When you write a screenplay, what is your typical writing process?

KK – When it comes to screenplays, I read the original book or/and hear the ideas of others at first, then play with them a while, and, eventually, write it by myself without asking anyone else’s opinion.

JC – Which qualities do you look for in actors in order to cast roles? When and how often do you refilm?

KK – I don’t refilm. Even if I wanted to, there is no capacity for time and budget in Japanese commercial movies. As for casting, I consider it some sort of destiny. We think somebody is good for a role, she/he also likes the script and the role. And it has to go well with the schedule and guaranteed fee. When everything works well, it becomes automatically the best casting.

JC – In Japanese movie culture, in what kind of position are you or your works placed? And how about in the global movie culture?

KK – I myself cannot say objectively where I would be positioned in Japanese movie culture. However, I feel that I’m at the middle. Not at the top, not at the bottom. This doesn’t mean that I’m in the centre of the culture, of course. I understand myself as being at a small corner of the culture. And in the wider, international world? Many Japanese movies are introduced abroad – and my works would probably be positioned also at the middle of the edge of them.

Image at the top by Bittermelon