Brazilian director Karim Aïnouz’s Madame Satã, celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. This groundbreaking LGBTQ film is a racially and sexually charged piece of cinema. Raw and intense, it belongs in the present as much as the past. Blessed with a timeless aura, even if the cinematography gives away its age, the film will resonate with today’s audiences, for the hostility it depicts towards the expression of one’s racial and sexual identity.

The story is inspired by the real life figure João Francisco dos Santos, who passed away in 1976. Played by Lázaro Ramos, Aïnouz undoubtedly takes creative licence in the portrait he crafts. Who was this icon of Brazilian culture? The short and simple answer is that he was a groundbreaking gay performer, who shattered accepted conventions, and fulfilled his dream of being a star. In keeping with his aspirations of stardom, his costume designs drew inspiration from Hollywood, including Cecil B. DeMille’s musical comedy, Madam Satan (1930).

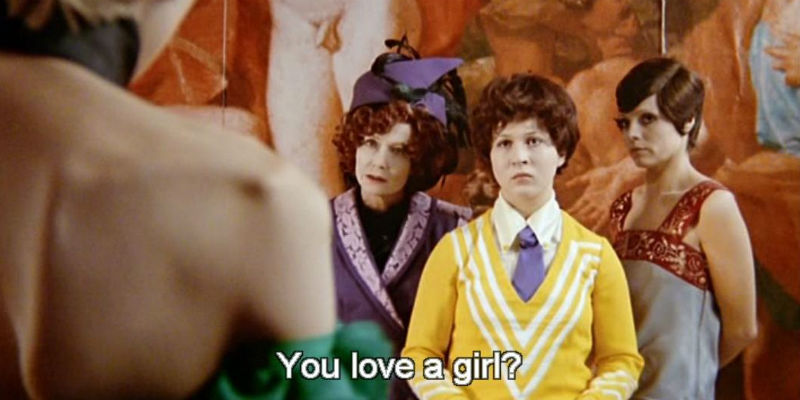

João Francisco dos Santos the man, had a dramatic life offstage to rival his onstage character. A convicted reoffender, he was a fierce street-fighter and a father. He gave a home to prostitute Laurita (Marcelia Cartaxo) and her baby daughter, and was friends with Tabu (Flavio Bauraqui), a vibrant hustler and prostitute.

Madame Satã has a contradictory vibe. It’s visually alive with the movements of the bodies, but the emphasis on the spoken word leaves the audience with the feeling that we’re witnessing a flamboyant hybrid of cinema and theatre. It’s an echo of João’s personality, that sees the aesthetic connect with the character. Laurita tells him in one scene, “You’re like a wild animal.” While João only aspired to be a star on the stage, his vibrant persona feels as if it were destined to appear on the screen.

The character captivates, yet there’s a restraint. Aïnouz refuses a critical exploration of dos Santos and Madame Satã. Some audiences will perceive the absence of a deeper character study, and accuse the director of being seduced by the personality of his protagonist. The point, however, is to become lost in the frenetic lifestyle of dos Santos, that allows the quieter and intimate moments, particularly with Laurita and Amador (Emiliano Queiroz) who runs the Blue Danube Club, to take us deeper into his persona.

Aïnouz effectively captures the internal conflict, which emerges gradually, rewarding the patient viewer. It slowly opens itself up to the audience, and by its conclusion, we are rewarded with an interesting insight into a captivating man, far from at peace with himself, and is seen as provocative by others.

The 20th Anniversary celebration of Madame Satã plays at the BFI Flare on March 20th 2022, in a joint screening with DMovies and African Odysseys. Just click here for more information, and secure your ticket as soon as possible!