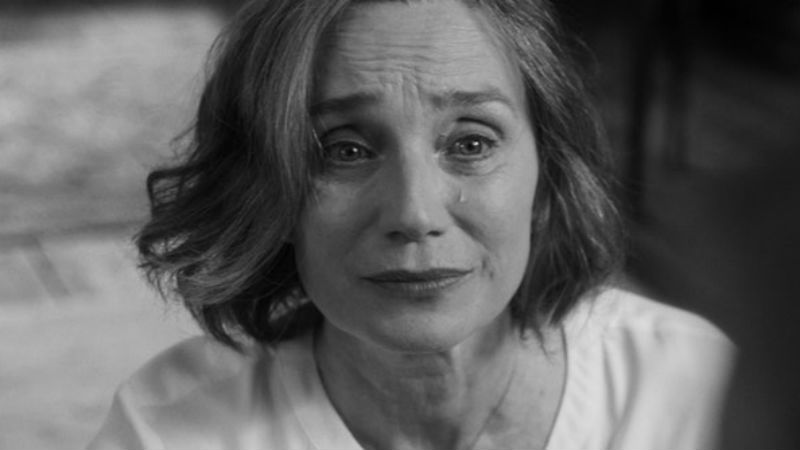

Ana (Diana Cavallioti) is a university girl to whom most people would find it difficult to relate. She suffers from depression, anxiety, panic attacks and she’s prone to all sorts of emotional outbursts. To most, she would be simply “annoying”. Her family background is deeply dysfunctional, and there are clues to suggest that she was molested by her stepfather as a teenager. She is unable to voice with the origin of the woes, and she struggles with the various types of medication she has to take. Yet her fellow student and boyfriend Toma (Mircea Postelnicu) is extremely patient, comprehensive and supportive of the extremely unstable and vulnerable young woman.

This might sound like the perfect plot for a languid and dire movie, or an unabashed tearjerker. Yet Ana, mon Amour has enough vigour, candour and pronfundity to make for a very convincing and compelling 127-minute viewing experience. The movie shuns a traditional chronology in favour a very irregular zigzag. Ana and Toma move back and forth in time from the early days when they met to their marriage, children all the way to separation. At time you won’t be able to determine when the action is taking place, and that’s ok. There’s no build-up towards an epic revelation at the end of the movie, and the dramatic strength of the movie lies instead in the subtles twists of fate and gradual changes of personality, supported by very strong performances.

Tamo will constantly seek answers to Ana’s mental health problems, but he will often fail to find them. Audiences will embark on a similar quest, being able to join some dots, but not all of them. Tamo will slowly begin to experience uncertainties of his very own, and he too will turn to others for support: first a priest then a psychoanalyst. The jolly, generous, affable and emotionally balanced young man will begin to morph into something else, and so will Ana. Those who identified themselves with the highly likable male character in the beginning of the film have a surprise in store waiting for them, as he too falls prey to his fallibility.

The anatomic realism of Ana, mon Amour is certain to be misinterpreted. Prudes will cringe dismiss some of the scenes as “unnecessary”. There’s real sex and ejaculation, a bloodied vagina following an unidentified medical episode, plus Toma applying cream to his son’s penis. These sequences are never exploitative, in fact they are rather fast and banal, even tender in their simplicity. They are still enough to unsettle Brits uncomfortable with anything too close to the bone.

Ana, mon Amour showed at the 67th Berlin Film Festival, when this piece was originally written. Forty-one-year-old Călin Peter Netzer won the award just four years ago with the film Child’s Pose. It is showing at the BFI London Film Festival.