I have waited for many films to arrive, but there’s only one that I’ve anticipated for 16 years: Terry Gilliam’s long-awaited The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Over the years it has even invaded my own dreams, quite fitting for a film made by a dreamer about a dreamer. I’ve followed its numerous iterations, from the initial hope that Johnny Depp would still star (following the success of those pirate films, he ruled himself out in 2009), to the Robert Duvall/Ewan McGregor two-header, and on to perhaps the most heartbreaking and tantalising version with John Hurt as the Man of La Mancha. At one point Gerard Depardieu (with Depp as Toby) was in the frame, then even Al Pacino was considered. Others have come and gone. In fact, the project goes way back, to a more literal concept with Sean Connery and Danny DeVito that Gilliam floated in the early 1990s.

Obviously, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was always set to play at Cannes. It was going to be independently funded with European money, and that’s where the festival directors and distributors gather. However, when former producer Paulo Branco attempted to sabotage it after leaving the project in what looked like a blatant attempt at extortion, everything was up in the air until the last minute. Without Branco’s machinations, the film would probably have played in competition – but in the end, Gilliam’s premiere bagged the final slot, showing the closing ceremony and… out of competition! It also garnered a 20-minute standing ovation despite festival fatigue, one of the longest ever.

With uncertainty still raging days before Cannes, I chose to trek to Paris instead, where screenings had been scheduled and looked likely to go through. With no UK distributor lined up, I wasn’t taking any chances on missing something I’d waited 16 years for, and so grabbed for the earliest screening I could.

How much of that Cannes ovation was for the film and how much for Gilliam’s perseverance is open to question, but in my opinion it’s probably his best work since Brazil (1985), and so richly deserved. Of course, Cannes reactions are not necessarily the best indicator of how well a film will perform with critics or audiences. No one was sure what to expect – from around 1989, when Gilliam was still a hot property in Hollywood, to now, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote transformed from a more faithful retelling of Cervantes’ lengthy and perhaps ultimately unfilmable novel to a meta-version that incorporated elements of Mark Twain’s novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court to a deeply personal contemporary version without the time travel angle once considered. The documentary Lost In La Mancha (Keith Fulton, Louis Pepe, 2002) showed something very different than the final film.

.

As personal as it gets

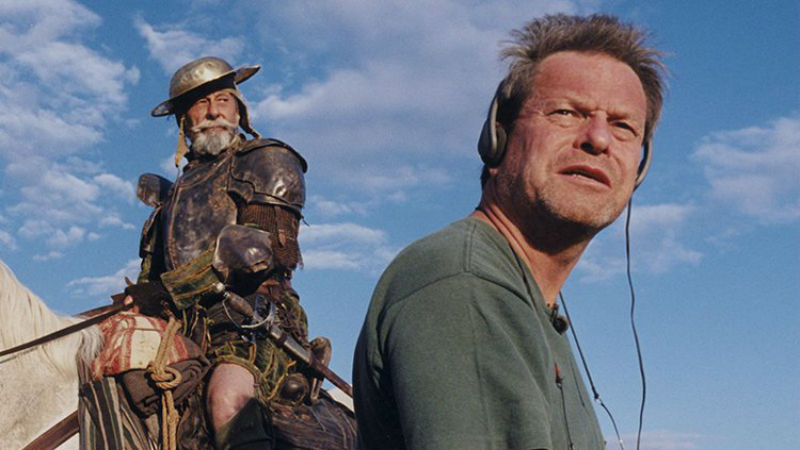

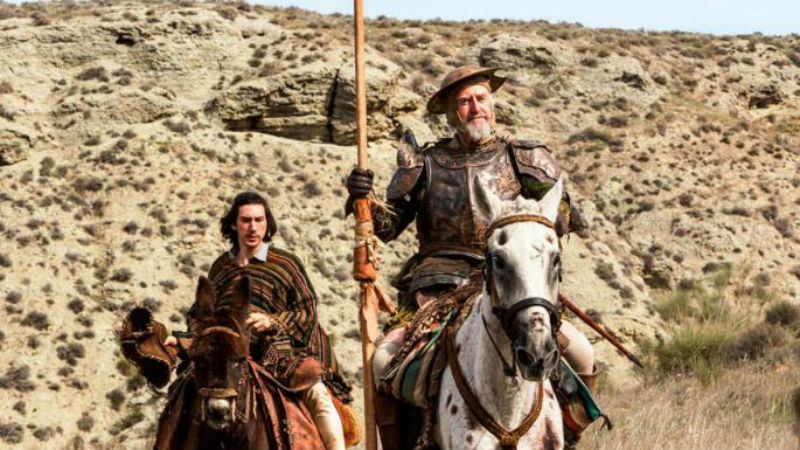

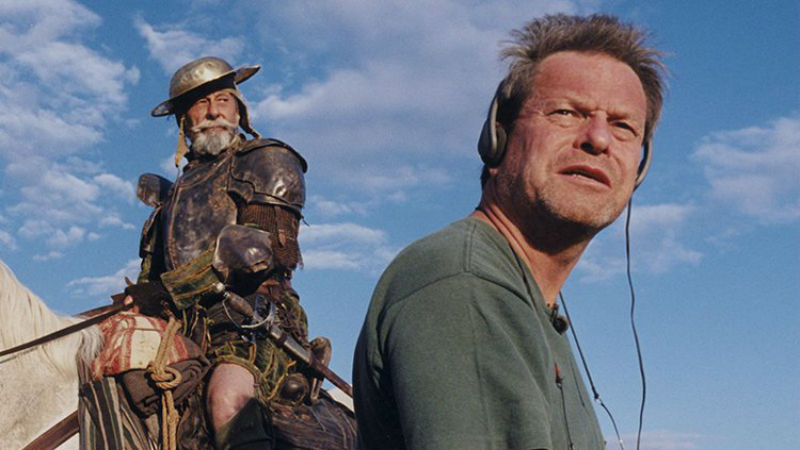

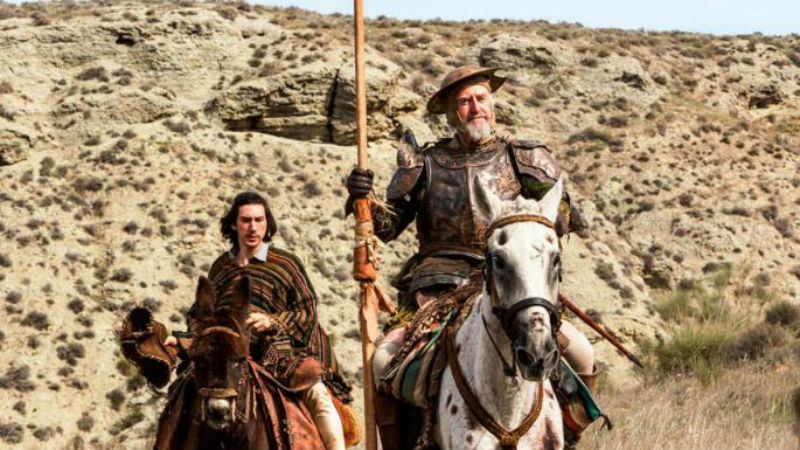

At some point in the noughties, co-writer Tony Grisoni suggested that lead character Toby should be a movie director rather than an advertising executive. And so Toby (Adam Driver) emerged as a youngish filmmaker who made a student movie called The Man Who Killed Don Quixote for his thesis. Now back in Spain to make a Quixote-inspired advert, he finds out that the town he shot as a student is close by. He visits to find some inspiration, and learns that his film had a profound, and not necessary positive, impact. That’s especially so for the village shoemaker, who played the role of Quixote (Jonathan Pryce) and now seems to believe he really is Cervantes’ knight.

Obviously, the film owes a massive debt to Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), which had a major impact on Gilliam (Brazil‘s original title was 1984 ½): a key scene for him was when Marcello Mastronianni dances around the film producers who are coming at him from all directions, a visual that portrayed what would be necessary to work successfully in the movies years to Gilliam before he made a film. Like all of Gilliam’s films, despite being grand, it’s intensely personal. Toby and Quixote portray the director’s two sides: Toby personifies the deeply frustrated would-be artist whose passion and determination have been channelled into commerce, while Quixote is the dreamer whose life was enriched and yet damaged by the story.

The film business is full of damaged people whose lives are lived episodically through the films they make. And when a film crew comes to town, it affects the place socially and even environmentally—living out your dreams carries untold risks. Indeed, there were accusations that the filmmakers damaged a world heritage site in Portugal while this one was made. The thin line between madness and dreams is always the main theme in Gilliam’s work, and there are certainly echoes of The Fisher King (1991; one of his few fully contemporary films), The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus (2009) and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) here. Gilliam has joked over the years that his wife, Maggie Weston, says he just makes the same film over and over. Of course, most true artists have certain themes that permeate their work and they constantly re-evaluate those questions because they are close to their heart.

.

A star-studded cast

The casting is exemplary. Adam Driver came to fame as the only reason to watch Lena Dunham’s TV series Girls, but in the last few years he has been able to pick off the directors he wanted to work with, from Noah Baumbach to Jim Jarmusch to Spike Lee. His Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017) role brought stardom, and attaching him to the project helped Gilliam sell the film overseas. Driver isn’t a stereotypical handsome leading man—he has an interesting face but isn’t a pretty boy, and here he perfectly captures Toby’s humour and arrogance. His comedic timing is coupled with enough depth to bring you along on his journey.

Jonathan Pryce has a long history with Gilliam—his breakthrough role was the lead of Sam Lowry in Brazil, and although he had been pegged for a different role in 2001, in 2018 he reached the age where he can pull off the role of Quixote but still has box-office power. He stepped into the role of after Gilliam’s old Python buddy Michael Palin was touted for the role and there was even a mock-up poster made for that version for Cannes.

Stellen Skarsgård is great as an absolutely horrid producer (perhaps there’s a bit of Branco in there) and Rossy de Palma also shines in a supporting role. Jason Watkins plays Toby’s assistant and perfectly captures a particular campy, upper-middle-class film agent type. The cast is filled out with Spanish and British actors who have perfect faces for a Gilliam production and Joana Ribeiro as Angelica is destined for stardom.

.

The eye of the Man of La Mancha

The film was shot by Gilliam’s own Sancho Panza, Nicola Pecorini, who’s a genius cinematographer but rarely gets works. Pecorini has worked with Gilliam ever since Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), despite a blip during Brothers Grimm (2005). Blind in one eye, he always comes up with interesting shots. Unlike a lot of Gilliam’s movies, there’s a lot of fish-eye lens work along with the trademark wide lens shots. Of course, the landscapes they found in Spain and Portugal do half the work. There are a couple of jump cuts that don’t work for me, but that’s a minor criticism. There is little CGI, which I think is a good thing and there is even a line about Toby preferring handmade effects than CGI. It’s difficult to get the budget for high-quality CGI, and the handmade quality fits the kind of film that Gilliam wanted to make.

.

A long cinematic journey

In other words, it was worth sleeping on the overnight bus from Leeds to Paris just to see The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, not once but twice: first at the UGC Cine Cite Halles multiplex, then at the MK2 Beaubourg, where the audience was smaller but far more enthusiastic. There were a couple of walkouts at both screenings, but in my experience that’s usually a good sign – the director has provoked a strong reaction (although at the MK2 it looked more like a ‘wrong date movie’ situation.) My attempt to blag a poster were, sadly, unsuccessful.

He’s a director who always struggles with length, and it’s Gilliam’s longest film since The Fisher King in a world where independent films are supposed to be 100 minutes max, it’s great that he was able to grab the time it needed—despite some minor pacing issues in the middle, it’s a story that needs time to unfold. If this is Gilliam’s last film (which I hope it isn’t), it’s a good one to go out on. At a time of so many mundane independent films and action/superhero films, the fact that Gilliam can still make a film every few years gives me hope for cinema, because that means it’s still possible to put his dreams and nightmares on the big screen.

…

.

Click here for our editor’s take on The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. He was present in Cannes, and far less impressed with the movie.

This leaves an hour and a half for the third flashback about the love of his life which again features Dolmaire as Paul in his student days, occasionally mediated by present-day recollection scenes featuring Amalric. It’s the story of his initially tentative, subsequently full on and finally disastrous romance with Esther (Lou Roy-Lecollinet, recently seen in

This leaves an hour and a half for the third flashback about the love of his life which again features Dolmaire as Paul in his student days, occasionally mediated by present-day recollection scenes featuring Amalric. It’s the story of his initially tentative, subsequently full on and finally disastrous romance with Esther (Lou Roy-Lecollinet, recently seen in