Mark Cousins’ Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema is a follow-up to his earlier work, The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2016). Again he explores how movies are made, but this time through hundreds of clips from films directed by women.

In actress Tilda Swinton’s introduction voiceover, she says, “Most films have been directed by men; most of the so-called movie classics were directed by men. But for 13 decades and on all six filmmaking continents, thousands of women have been directing films too. Some of the best films. What movies did they make? What techniques did they use? What can we learn about cinema from them? Lets look at film again through the eyes of the world’s women directors. Lets go on a new road movie through cinema.”

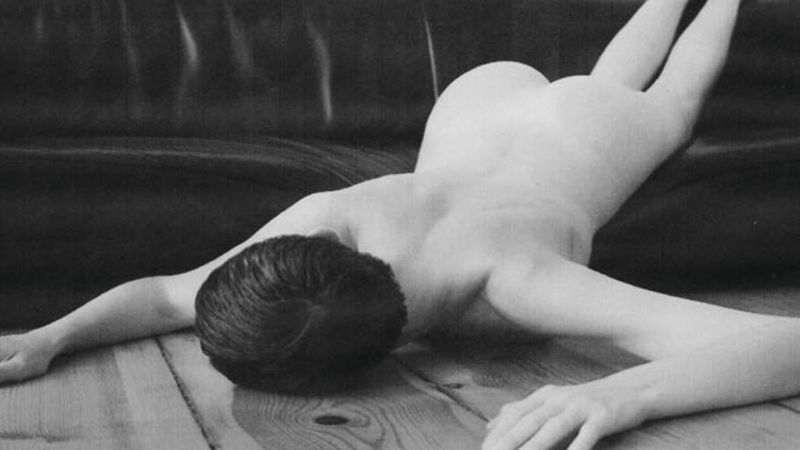

The documentary is structured around a series of “how to” questions, the film broken down into 40 chapters that begins with Openings and ends on Song and Dance. In between are chapters discussing a range of subjects, amongst them: believability, framing, tracking, dream and bodies.

In conversation with DMovies, Cousins spoke about being drawn to the external world rather than his internal world, the need to bleed cinema of gender generalisations, and how we all have the power to instigate a change to keep the contributions of women filmmakers alive.

…

.

Paul Risker – Film and storytelling to my mind is a process of answering questions. Would you agree, and what led you to decide to structure the film with a series of “how to” questions?

Mark Cousins – I don’t think I’ve heard the idea that filmmaking is about asking questions, but I can see what you mean. I always ask myself, “How do I avoid banality?” Another way of saying this is, “What is the form?” The conventional way of looking at the great female filmmakers would be chronological, or looking at industry employment trends, or doing interviews, or to report on the Weinstein revelations. I decided to do none of these things. Instead, I wanted to focus on the work of the filmmakers, not their gender or victimisation. Once you decide to look at the work, then – if you’re a filmmaker rather than a more theoretical person – you end up, by a process of elimination, asking “how” to questions.

PR – One of optimistic impressions to take away from Women Make Film is that in spite of women filmmakers being marginalised, they’ve found a way to express their creativity. Would you agree that this is a source of optimism?

MC – I agree that Women Make Film is a work of optimism, or I’d say affirmation. It’s about what has been made, rather than what hasn’t been made. I passionately believe in structural change in the film world and the revolution against sexism, but – also – years ago I became a bit impatient with those activists who hadn’t actually seen many of the thousands of films directed by women.

Also, I don’t quite see the great films directed by women as a sign that human storytelling can’t be silenced. I don’t think that film is necessarily a storytelling medium, to be honest. I realise that sounds contrary, but many of my favourite films: Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), Vagabond (Agnes Varda, 1985), The Asthenic Syndrome (Kira Muratova, 1990), 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), D’est (Chantal Akerman, 1995), etc, aren’t really very story driven! And on your bigger point about creativity: Again I don’t want to sound contrary, but when people make films (or make anything) they are not necessarily expressing themselves! I certainly don’t have a rich inner life that I’m desperate to share with the world. It’s the world, the outer life that is rich, and I use my cinema to clock it, to bear witness to the richness and to throw my anchor onto it.

PR – In your opinion, does it harm cinema to have a focus on gender? Should the end goal be beyond equality, reducing the focus on gender to appreciate the filmmaker as “filmmaker?”

MC – Focusing on gender was a necessary means to an end. I hugely admire the pioneering film feminists of the 1970s and since, who came up with ideas such as the male gaze. But the end was not, I think, to identify and separate male and female cinema, as if they are black and white chess pieces. The idea, surely, was to out the unacknowledged power and gender imbalances in film production and aesthetics. Once that was done and at the very moment it was done, it was also important to bleed cinema of gender generalisations, like you bleed a radiator. There is nothing gendered about the movie frame; it’s an androgynous rectangle, and that’s one of the reasons why shy people and queer people in particular like it. To go to the cinema is to escape the pressure to be what a man or woman is supposed to be like. The voice-over artists in WMF have all brilliantly embodied that in their work.

PR – In your video essay on the Blu-Ray release, you speak about your collaborators who watched films, suggesting scenes, supporting you in researching and making the film. Hearing this, my immediate thought was how we can only understand film together – filmmakers, critics, audiences, academics and scholars, amongst others including technicians and actors. To my mind, you remind us of the importance of a community of ideas, of sharing to fully understand cinema.

MC – In my real life, I totally agree with you on this. Co-operation is one of the biggest themes – it’s the final message in the first great poem, the epic of Gilgamesh, for example. And yes, my collaborators on this film were great: John Archer and Clara Glynn at Hopscotch Films, my regular editor Timo Langer, executive producer and voiceover artist Tilda Swinton. The other voiceover artists: Jane Fonda, Debra Winger, Sharmila Tagore, Kerry Fox, Adjoa Andoh, Thandie Newton. Our London-based researcher Sonali Battarachya, the great LA film historian Cari Beauchamp, etc. But I hope you don’t think I’m again trying to disagree with you! My desire for cinema has always been a solitary thing. I’m quite an anxious person, and am often worrying what other people around me are thinking. Alone in front of the screen, such social and psychological worries ebb.

PR – Do you believe access to film should continue to be a concern? I ask because there are filmmakers featured in this documentary whose work audiences will likely only see these small glimpses.

MC – Definitely, and Women Make Film is a shoulder to the wheel of advancement. Many of the filmmakers featured within it are dead, but that doesn’t mean that their work has stopped contributing to film culture. In some cases – for example the McDonagh sisters in Australia, who were successful in the silent time – the directors have stopped (been prevented from) contributing to movie culture. We can make that change; everyone reading this can make it change.

PR – Speaking with Pollyanna McIntosh about her feature directorial debut Darlin’, she told me, “I’d love to just never talk about the film and just let people experience it how they experience it, because you don’t make a film to say: This is what the case is, this is the truth”. Do you agree with this sentiment, and what are your hopes for the experience of the audience?

MC – Totally. On the day that I complete a film, I want to stop speaking about it because the thinking is over, the picture is locked, the sound is mixed. The reason that I do speak about my work a bit is because it’s a tough world out there for fledglings.