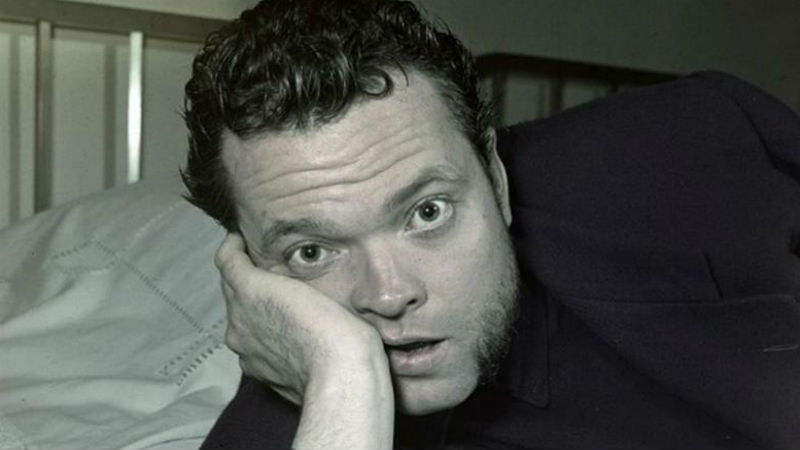

Shakespeare’s tragedy has been adapted for the screen since the earliest days of cinema, with D.W. Griffith making a version in 1916 (now considered lost). Orson Welles and Roman Polanski followed suit later in the century. It’s was transposed to feudal Japan in 1957 with Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (perhaps the best adaptation), and at least twice as American mob films with Men of Respect (William Reilly, 1991) and the wonderfully silly titled Joe Macbeth (Ken Hughes, 1955). In a rare solo outing as writer/director, Joel Coen draws upon on the lineage of Macbeth on screen, particularly the Orson Welles, adding his own unique stamp on it.

Joel Coen doing Shakespeare may seem strange, but the Scottish lord is very much a Coen character. Power-hungry Macbeth, the Thain of Cawdor, is a military leader who is close to the throne. After three witches tell him that he will be king, he takes matters into his own hands, starting with the murder of the king. He then goes after anyone else who could get between him and his destiny, with his equally ambitious wife encouraging him to act.

Macbeth is a man whose trajectory, through circumstance and violence, takes him in a negative direction. He’s full of anxiety, and it’s a crime story as well. Through a series of extreme events that have higher stakes as they go along, he kills his way to the top, and then gets his comeuppance. It’s not dissimilar to A Serious Man (Coen Brothers, 2009), where circumstances and choices lead to terrible events. He is a character stuck within his own fixations, with no good way out, and that is a Coen Brothers staple.

Denzel Washington plays Macbeth, in a fine example of colour-blind casting. Denzel is a trained Shakespearean actor. He goes for a big, shouty Macbeth instead of a more brooding internalised take, so depending on your preferred way to tackle the character, your mileage may vary. It’s a show-stopper of a performance: no way around it, Denzel is the first serious Oscar contender for Best Actor this year, and I wouldn’t be shocked if he brings home a third Oscar come March.

The story is pared down, as is typical for an adaptation. This lean version runs at about 105 minutes, slightly shorter than the Welles version and around the same length as Throne of Blood. Frances McDormand plays Lady Macbeth, and gives a more sympathetic take than some versions. She’s not a overwrought character at all, with McDormand turning in a much quieter and more restrained performance than Washington. You get the sense that she absolutely loves Macbeth, with that coming forward as her motivation more than her own ambition.

Like the Welles version, the film was shot entirely on a Los Angeles sound stage, with no exterior or location shots. Bruno Delbennel is Coens’ go-to cinematographer when they can’t get Roger Deakins, and worked with them on three of their last films. It was shot digitally in silvery black and white, and the result lands somewhere between stagy and surreal—it has a feel that’s not dissimilar to a German expressionist film. Even the set design is pretty stripped down, just the blocks of the castle and unique framing, with a lot of fog to fill in. In the Welles film, a similar choice was made for budgetary reasons, but here it’s more of an aesthetic choice. Old black and white film stock would have been my preferred medium, but that’s not the world we live in—it is only their second digital feature. They use shots to make it a Noir Macbeth, and you can see frames that remind you of the Coens’ most noir film, The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001). Regardless, visually it’s fantastic.

One actress (Kathryn Hunter) plays all of the witches, which was an interesting casting decision. Hunter is a Shakespearean actress known for her physicality, and turns in an unearthly performance. Brenden Gleeson plays King Duncan, in a role that feels tailor-made for him. Harry Melling is Malcolm, and gets the right tone for this ambitious rival. Melling has come a long way from Dudley in Harry Potter, he seems to be in everything these now. Coen mainstay Stephen Root has a fun small part as the Porter.

It’s a very good adaptation with an otherworldly feel, helped as always with a Carter Burwell score, who has been the Coens’ composer of choice since Blood Simple.

The Tragedy of Macbeth premiered at the BFI London Film Festival. It will be in UK theatres in January, then streaming on Apple+.