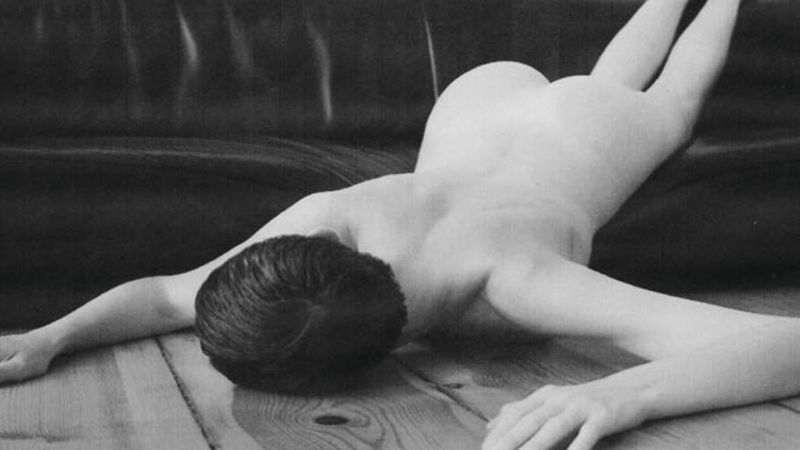

The latest issue of Doesn’t Exist is entirely devoted to the work of Powell and Pressburger, and it features interviews with film historian Ian Christie, journalist and documentarist Mark Cousins and filmmaker Sally Potter. In addition, the magazine includes a recreation Michael Powell’s iconic Peeping Tom (1960) in fashion photoshoot format.

This article contains only the interview highlights. Click here in order to find out more about Doesn’t Exist, and to acquire your luxury hard cover edition right now with the full interview.

…

.

Victor Fraga – You have declared that Powell and Pressburger have influenced you. Could you please tell us how?

Sally Potter – They influenced me not only by their films, but by their collaborative working process and by their attitude. They took risks and made them work. Their films are lyrical, bold, political, poetic, theatrical, passionate, sly, ironic; breaking multiple conventions and yet screening in big cinemas to audiences who accepted their – sometimes – wild inventions. They were as culturally agile as acrobats on a tightrope walk, in ways that reflected their individual sensibilities; an alchemical mix of Powell’s British theatrical entertainment roots and Pressburger’s East European literary and musical roots. Their collaboration was an inspiration; a mutually generous way of working that produced a singular voice.

VF – The male gaze is prevalent in Peeping Tom [Michael Powell, 1960], and the serial killer protagonist is a mostly likeable character. Do you think that the film fetishises femicide? Could it be made in the 21st century?

SP – I never saw it as fetishising anything. It was an unflinching study of the mysterious and sometimes ruthless act of looking, as a filmmaker. Is he likeable, really? I don’t think that was the goal. The most disturbing aspect was the use of the genuine fear of his son in one scene. Of course, the film stopped Michael Powell’s work in its tracks. From that perspective, it was a self-defeating disaster.

VF – How would Orlando have turned out had the filmmakers or only Powell directed it? Or was this always a film destined to be made by a woman?

SP – I don’t believe in destiny. Making Orlando was a repeated act of will in the face of the utter disbelief and active discouragement of funding bodies and financiers, leading to near bankruptcy. But we made it. Like Virginia Woolf, I never thought of the mind of the artist – in this case mine – as gendered. My focus was entirely on what I could do with the subject, not on who or what I was while I was doing it. The subject itself, however, was a series of questions about the politics of gender, set in the context of an exploration of time and impermanence. Undoubtedly my experience growing up female influenced many of my directorial decisions about how to tell the story. Michael Powell was linked to the evolution of the film. He sat regally at one entirely unsuccessful fund-raising event in New York City as a show of support for the project. His face, dignified posture and quietly enthusiastic demeanour remain vivid and deeply touching in my memory. His presence and encouragement were worth infinitely more than any finance we hoped to raise.

Alex Babboni – Powell played a crucial role in supporting and mentoring you during the early stages of your career. What was that relationship like?

SP – The relationship was occasional but intensely meaningful to me. I interviewed him for my television series Tears, Laughter, Fears and Rage and sometimes wondered if I had set the entire thing up so I could get in a room with him for a day. We met a few times elsewhere. Tilda Swinton and I went to see him in the countryside, where he was living with his beloved Thelma Schoonmaker, and we walked in the woods and talked. During another visit in New York City, he told me about his own preferred work from their oeuvre was A Matter of Life and Death. I also saw a Q&A after a screening of Gone to Earth, where he and Pressburger stood side by side radiating deep love for each other. I hung about shyly afterwards and somehow caught their attention. We talked, briefly, and their words nourished me for years to come. It taught me to always try to communicate generously with people hovering around after a Q&A, with that unmistakable look of longing and admiration in their eyes. Even a few apt words and some direct eye contact can make a big difference. As theirs did for me.

…

.

The image at the top is from ‘Peeping Ton’, and it belongs to the BFI Archive. The other image belongs to Doesn’t Exist.