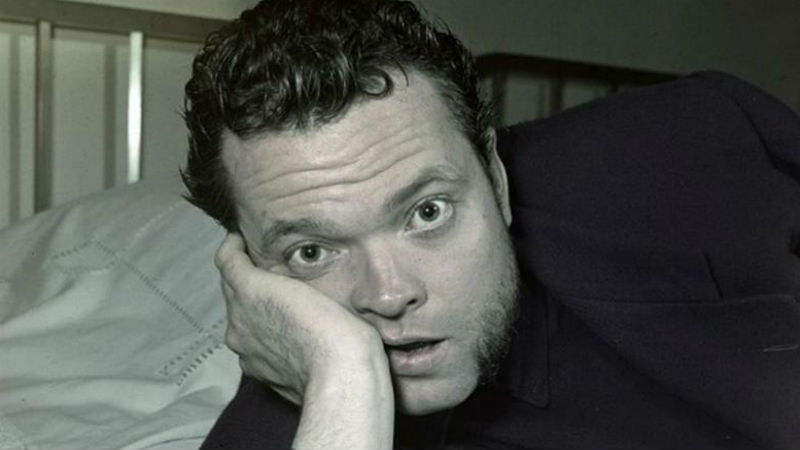

This takes the form of a letter, as in, a letter to Orson Welles read out by director Mark Cousins on the film’s soundtrack as the film proceeds. According to the press blurb, Cousins never wanted to make a film on Welles feeling that numerous books and documentaries had already said everything there was to say. But then Cousins was presented with an unexpected opportunity. He was given access to a box of hitherto unseen drawings, paintings and sketches by the great man. These, he felt, gave him a way to represent a side of Orson which hadn’t really been seen before.

So Cousins starts off in New York to Albioni’s doom-laden Adagio, today a familiar film music staple which was first used in Welles’ screen adaptation of one of the 20th century’s great dirty texts, Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial (1961). Welles himself, and the wider body of work which bears his name, is another of those dirty texts and Cousins proves himself exactly the person to have another crack at documenting him with the drawings and paintings from the box the perfect vehicle for that journey. For the newcomer to Welles it’s a great starting point; for the more knowledgeable viewer there’s a wealth of never before seen material here.

The whole breaks down into separate sections discussing Welles with regards to Pawn, Knight, King and – in a less chess-referenced epilogue – Jester.

The Pawn section deals with common people, starting with his mother Beatrice, A Christian Unitarian activist who got herself elected and ensured “a Christmas gift for every child” making a huge political impact on her son.

The more complex section on the Knight deals with several aspects of Orson’s love life – among them visual loving, chivalry and death/guilt. Up pops the four in a bed revelry from Shakespeare/Falstaff vehicle Chimes At Midnight (Welles, 1965) and a drawing of a devil who visits Welles when his then wife Rita Hayworth is absent. No drawing of Rita, but numerous clips from the film he built around her, The Lady From Shanghai/1947, including the transcendent sequence where whilst lying on the deck of a boat she requests a cigarette and the camera framing her face moves to follow down her arm to a cigarette coming into her hand which she then brings back up to her face.

As for the King,in the opening minutes there’s an unspoken reference to Donald Trump. The current Potus is reminiscent of various despotic characters created by Welles: newspaper tycoon Charles Foster Kane (Citizen Kane/1940), murderous monarch Macbeth (1948), racketeer Harry Lime (The Third Man, Carol Reed/1949) and corrupt cop Hank Quinlan (Touch Of Evil/1960). Cousins suggests current the state of the world would fascinate Welles whose formative years included the 1930s’ stock market crash, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism which lead to WW2.

The rather different Jester section has Welles (voiced by Jack Klaff) writing back to Cousins, suggesting that all the world’s a circus. Cousins’ imagined Welles throws up various ideas that don’t fit the film’s thesis – the japes of Welles’ home made Too Much Johnson (1938), the absurdist world of Mr. Arkadin (1955) and a series of drawings of St. Nicholas which gradually turn Santa Claus into a drunkard with a bottle.

It all works extremely well as a film, whether you already know Welles or not. That said, the wealth of material here cries out for additional exposure in other media – a book of pictures, an art exhibition or an interactive website. You can see that just from watching the trailer. For the moment, though, this film version will do just fine.

The Eyes Of Orson Welles is out in the UK on Friday, August 17th.

Previews plus a Q&A with director Mark Cousins at various venues across the UK and Ireland:

Sunday, August 12th: Glasgow Film Theatre

Tuesday, August 14th: BFI Southbank, London

Wednesday, August 15th: Bertha DocHouse, London

Thursday, August 16th: Watershed Bristol

Friday, August 17th: Home, Manchester

Sunday, August 19th: Dundee Contemporary Arts

Sunday, August 19th: ICA, London (with Jack Klaff not Mark Cousins)

Tuesday, August 21st: Strand Arts Centre, Belfast Film Festival

Wednesday, August 22nd: Irish Film Institute (IFI), Dublin (also, Welles season)