While it is known that in 1613 Shakespeare returned from London to his birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon following the destruction by fire of his theatre, the Globe, there is no record of this period. Ben Elton, the scriptwriter, has created a touching evocation of this time, focusing on Shakespeare’s efforts to rebuild his relationships with his wife, Anne, and his two grown-up daughters, Judith and Susanna.

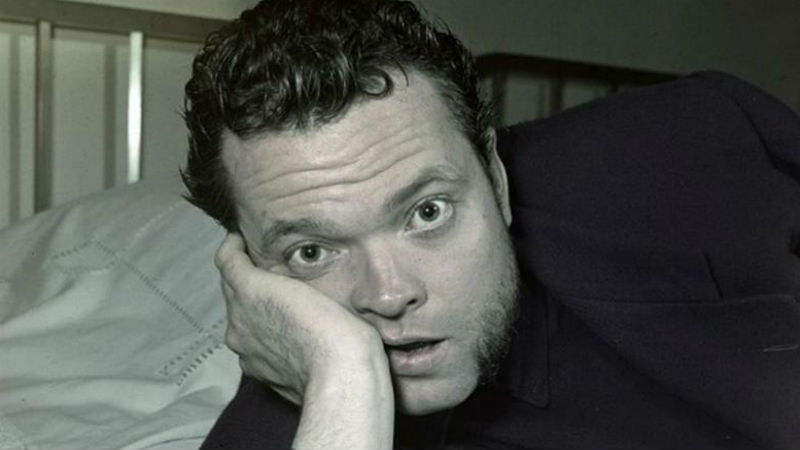

The central parts are played by actors famously distinguished for their work in Shakespearean drama, Judi Dench, Ian McKellen and Kenneth Branagh, who also directs the film. Each one of them a national treasure per se. In the depth of their portrayal of the characters, they succeed in presenting a rich family narrative much affected by the strong influence of the provincial values of the time. Shakespeare (Branagh) carries the stigma of his father’s poor management of money. The women of the family reveal the effect of discrimination against women. His wife Anne (Dench) is unable to read or write and their daughters are also denied education only available to boys.

While Shakespeare argues that he has done well by the family, ensuring that they have a lovely home and the financial means to enjoy their lives, the sense that the family left in Stratford felt abandoned is confronted. What hangs over them all is the death of Judith’s twin Hamnet some years earlier, at the age of just 11. This provides the central thread of the film. The background to the early death of Shakespeare’s only male heir is sensitively explored and allows for the development of changed relationships within the family. Gender, religion and social status all play a part.

One episode dwells on a meeting with the Earl of Southampton (McKellenn) who had travelled to see Shakespeare. The affection and mutual respect which they hold for each other does not prevent the Earl pointing up the social distance which exists, despite Shakespeare’s attempt to address the problem by buying his own coat of arms.

The production values are outstanding, as is the costume design. The interiors reflect the darkness of the period – the sitting room heated by a brightly burning log fire and illuminated by many candles. Wooden floors accentuate the sound of people moving about. The enclosed interiors contrast with rural landscapes and cloudscapes which provide the backdrop to Shakespeare’s efforts to create a garden in his son’s memory.

The pace of the narrative is rather slow, as befits a study of a man in the final phase of his life. For those familiar with the plays, identifying the source of the quotes which Branagh incorporates in his dialogue adds to the enjoyment of the film, but familiarity with Shakespeare’s plays is not essential to enjoying the film.

All is True is out in cinemas across the UK on Friday, February 8th. On Netflix on Sunday, January 3rd.